the zone of interest review

film by Jonathan Glazer (2023)

“Evil comes from a failure to think. It defies thought, for as soon as thought tries to engage itself with evil and examine the premise and principles from which it originates, it is frustrated because it finds nothing there. That is the banality of evil.” – Hannah Arendt

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

March 10, 2024

In the first few minutes of the film, we are immediately immersed in a black screen, allowing us to give the attention that film demands. Soon, we are taken out of that darkness and into the picturesque image of the Hoss family enjoying a rural outing by a river. As we see Rudolf Hoss for the first time, my first impression is of a gangly, awkward-looking, at best, mediocre man, nothing like the poster boy for the Aryan race or menacing monster one might imagine a person of his reputation to be. This impression is reinforced throughout the film by the banality of evil and images of one of many perpetrators of the mechanisms of death and destruction so coldly developed by members of the Nazi Party.

Most of the film takes place within the confines of the Hoss family home, a microcosm resting on the border of Auschwitz (called “Zone of Interest”), where only a stone wall separates them from the relentless atrocities on the other side. The idyllic family plot where we see Hoss’s wife and children conceals the ignominy of their collusion, giving what we cannot see a more resounding impact.

Glazer uses the setting by means of some audacious choices, never showing the inside of the concentration camp. Instead, we stay mostly in the boundaries of the family’s home, observing as they raise their children under the shadow of the never-ending mechanization of industrialized genocide, rumbling on with infernal resolve.

The use of sound design becomes an entirely ubiquitous structure, building on the fact that there are only fractions of what resembles a musical score present in the film. The sound plays a unique part in the film’s process as one of the main ways to perceive the horrors occurring on the other side of the walls, creating an almost entirely ambient experience of Auschwitz. There is not a single moment or frame at the family residence that we are not reminded of horrors taking place outside their walls. The sporadic yet consistent din of screams, gunshots, SS officers, barking dogs, and the constant thunderous sound of the incinerators turning bodies into ash.

One of the only revealing elements of the camp is the smokestacks, which illuminate the home in the evenings with their amber glow just beyond the walls. More importantly, the film focuses almost entirely on the perpetrators with minimal narrative structure and centers mainly on the daily lives of the Hoss family as they carry on with insignificant domesticity and the tediums of life’s daily tasks with unsettling disinterest and apathy, showing no signs of self-awareness or moral consciousness.

Its overwhelming clinical approach carries over to its characters through every scene and provides a vexing peek into such inhuman austerity. The Hoss’s laugh and joke in the comforts of their own beds, the children frolic in the pool, and Miss Hoss looks at herself in the mirror in a fur coat confiscated from a Jewish woman, whose fate is of no concern to her. Reading fairy tales to their children at bedtime to fill their minds with pleasant images within their dreams, the Hoss’s later remark on their home being their “dream” further reveals an egregious form of compartmentalization and a shocking revelation at the level of moral and emotional bankruptcy that would be required to consider the central component of the most significant mass genocide in history – “a dream home.”

Their garden, where much of the film takes place, is a telling look into the macabre heir of superiority that translates into playing god by husband and wife. Hedwig has her garden, and Rudolf has his just on the other side of the wall, illustrating the distressing fact that with enough attention to detail, you can sustain and nurture one life just as easily as you can erase another.

The camps are never seen because they do not exist to the Hoss family, with the exception of Rudolf. The only thing that exists is the interiors of their walls from where they inflict their putrid will on the world without ever getting their hands dirty, while those made to suffer below them will have their hands bloodied or soiled. And if by coincidence they find themselves exposed to the filth they have created, we witness their compulsive fear of bodily contact with that reality in a revealing scene where the family methodically scrubs themselves down after a day in the river that suggests what they are trying to scrub away cannot be cleansed. Giving very few glimpses of the victims, the film mirrors some sobering resemblance of who we are as a society and our own complacency as we seem to be leaning into a more regressive global stance on violence and nationalism.

Glazer commented on the film’s mostly still shots and absence of artificial lighting on the sets, relying on natural light, creating a more naturalistic setting through technical innovation and restraint. The day shots are periodically contrasted throughout the film with the only images of night shot with night vision of a young girl leaving food amongst the working areas of the prisoners, giving the film its only defiant stance against the final solution. Glazer said he needed to implement some presence of light or thematic resistance in a mostly sunlit film shrouded in such abject bleakness.

The sequence of the girl leaving apples for the prisoners at night is based on the actions of a real girl who died shortly after the film and had lived her life in the same house after the end of WW2. In his Oscar acceptance speech, Glazer dedicated The Zone of Interest to her, describing her as “the girl who glows in the film as she did in life”.

The Zone of Interest successfully creates an environment that normalizes human atrocities that we may never see but whose presence is always felt. It is a film I will never forget and revisit. As uncomfortable of a watch, it is a profound and dispelling example of human progress while using an observational perspective, placing us in an intimately close setting within these events.

Showing these people in their everyday lives evokes the ideas that philosopher Hannah Arendt was bringing to our consciousness. Dismantling them as spectacles shows the simplicity with which they carried out their lives and how a perceived average person can be capable of and implicit in something so egregious in a casually unconscious manner. Their ideologies are clearly stated in specific points of the film, giving some of these comparisons a possible conflicting message. Still, it made the point nevertheless, keeping all of it in mind.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

Following the everyday lives of a group of young theater performers from rural Fenyang, spanning the late 70s to the early 90s in the aftermath of China’s Cultural Revolution…

A decadent London aristocrat hires a man-servant to attend to his needs. However, the balance of power starts to shift. Joseph Losey’s 1963 film, The Servant is loosely based on…

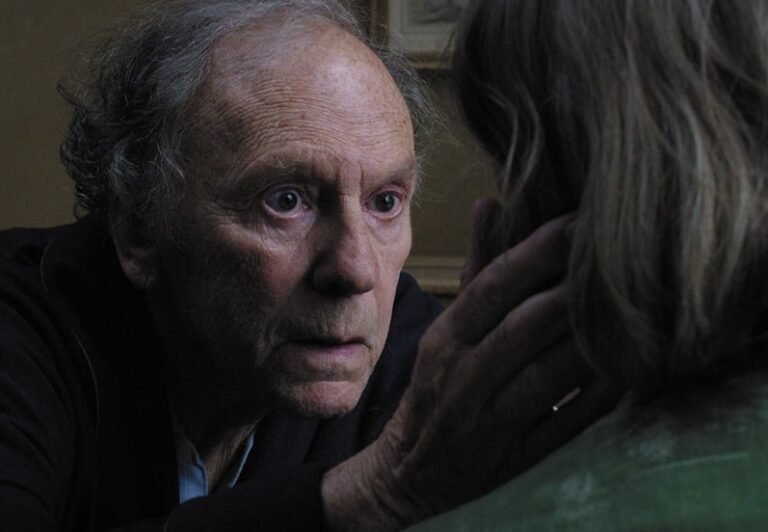

Georges and Anne are in their eighties. They are cultivated, retired music teachers. Their daughter, who is also a musician, lives abroad with her family. One day…

New German Cinema or Neuer Deutscher Film, is a film movement that started in the late 1960s, and thrived throughout the 1970s and 1980s. It represents a significant turning point…

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy was a country in ruins, both physically and economically. Amidst the rubble and despair, a group of visionary filmmakers arose to…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory…