the servant review

film by Joseph Losey (1963)

Joseph Losey’s 1963 film, The Servant, is loosely based on Robin Maugham’s novella. It was adapted for the screen by Harold Pinter (known for The Pumpkin Eater and Accident) and is one of many collaborative efforts between Losey and Pinter. Considered a provocative and risque work at the time of its release, it was shelved for a period but is now revered as a masterpiece.

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

April 28, 2024

Losey, who was blacklisted from the US during McCarthyism and the Red Scare, ended up relocating to the UK where he continued his work in filmmaking. “The Boy with Green Hair” was my introduction to his films way back in high school when I had a teacher who made us watch it in reference to my green mohawk on the last day of school. I have periodically watched his films ever since. The Servant strikes me as the most ambitious of the films that I have seen and certainly my favorite amongst his filmography to date.

The Servant tells the story of Tony (James Fox), a young aristocratic playboy who has just relocated to London. To the dismay of Tony’s equally privileged girlfriend, Susan (Wendy Craig), he hires Hugo (Dirk Bogarde), a valet, as his personal manservant.

Hugo’s overly comfortable and ubiquitous presence signifies a certain trust and co-dependency between Tony and Hugo, resulting in Susan’s immediate hostility towards Tony. Susan expects Tony to make himself invisible as he fulfills his duties, to be seen only when expected and not heard, and to know his place in what she rightly considers an outdated profession and relationship. But her seemingly more modern point of view is by no means a quality that inhabits other areas of her personality, which ring truer to the stereotypical snobbery of the bourgeoisie, characterized by crusts removed and raised pinkies.

Her irritation is also raised by her insular sense of privacy being invaded by someone whom she clearly sees as being beneath her, challenging her. Susan makes it a point to exhaustively remind Tony of his lower station, no matter how tenacious of an effort it requires to further dehumanize and degrade the target of her malicious ambitions, making a clear statement of her air of superiority that can also be seen as a reflection of the ruling classes’ stance and privilege.

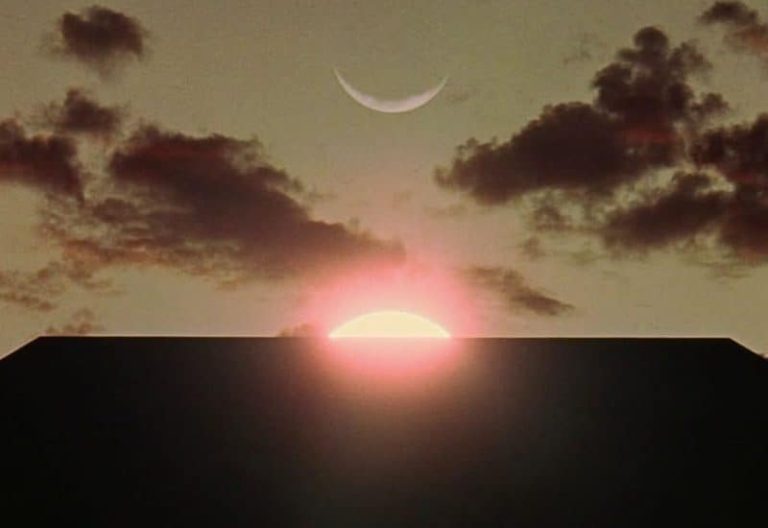

Susan’s plan to sow the seeds of division between Tony and Hugo backfires as the two men lean further into the master-servant relationship, marking the start of its evolutionary perversion. Through their bond, Tony is entrusted with hiring a maid for the house, bringing in his sister Vera (Sarah Miles) to fill the position. Vera’s bubbly and provocative persona serves as the final coffin nail in an already tumultuous and seductive environment that employs a ratcheting tension between its characters in ever-ensnaring compact surroundings created as a means to manipulate and invite a cagey ambivalence between “brother and sister” and master and servant, adding to its duplicitous and wayward language. As the dynamics of each relationship devolve into an undifferentiated funhouse perspective, the film grows increasingly darker in its aesthetics thematically and visually, further infusing a subversive maliciousness.

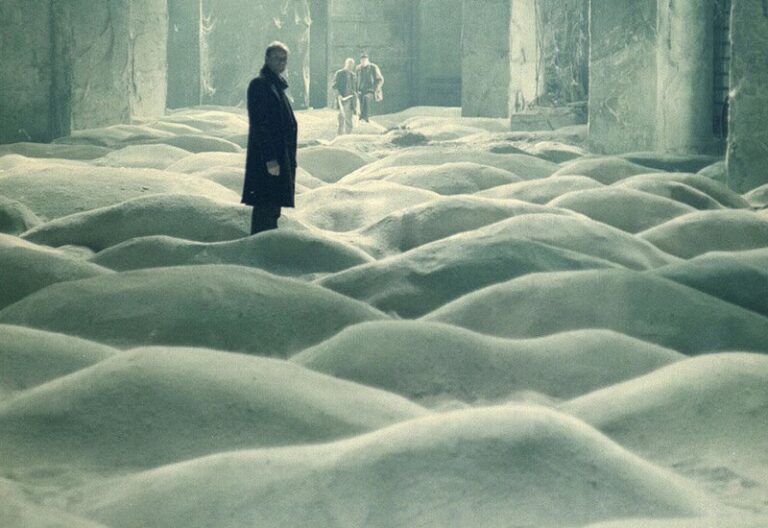

While Vera is complicit in physically seducing Tony, it is Hugo who acts as puppet master and sinister architect of debauchery, his actions more closely resembling a mad scientist experimenting on his guinea pigs while hiding behind the unassuming persona of a valet. In bringing Vera into the dynamic, there is a formidable reassurance of Hugo’s influence and a menacing example of his skewed sensibilities as he pushes the boundaries of his control over Tony. Hugo’s secret role as the true head of the household serves as a taint on the sacredness of the aristocratic homes of England’s landed gentry and a subversive delivery device to inject all of the controversial components that have always clearly been there, exposing the sadomasochistic qualities imbued in the master-servant relationship.

As Hugo usurps more control over the household by appealing to Tony’s basest urges, the film unfolds through its brilliant use of metaphorical and technical lexicon, elevating this genre blend of conceptualized wizardry into a masterful stroke of introspective cinema. Its unforgettable use of shadows, coupled with its brilliant use of mirrors, reveals truths and reflections about the characters that are hidden within, reversing the presumed natural order of things through the reversal of roles, genders, sexual orientations, power struggles, and fates and fortunes. The shadowy environment, in which the true nature of the home’s inhabitants is revealed through reflections in the mirrors and reflections through one another, decodes suppressed behaviors and psychologies, revealing our own clandestine dysfunctions. Paired with its equally ambiguous scene with the dripping sink, noticing the drip-drip method of a slowly increasing influence and manipulation onto its unsuspecting host resembling the duality of a parasite-host relationship.

The strong homoerotic implications are just that and as subliminal as they are, they represent a specific language in cinema that everyone acknowledges but that cannot be made explicit due to the oppressive social climate of a time when homosexuality and other so-called controversial subjects are left to rest just below the surface, meant for the most discerning of eyes to elude censors and condemnation while still having influence within an industry where the artists fought a subliminal battle with those in charge in a country where homosexuality was still an offense that would not be decriminalized until 1967.

The Servant takes an irreverent aim at the history of hierarchies, classism, and high society’s insulated culture and values. Furthermore, it is a subversive protest against scare tactics and proclamations of fear set against anything outside the status quo. The moral authority of traditional values put in place by those in charge of structured social doctrines and caste systems run by the powers that be is one and the same that blacklisted Losey from America which influenced Losey’s relocation to the UK.

The Servant lends itself to the noir genre while still maintaining its course within psychological horror and realism. It is an addition to the British New Wave and one of those rare instances where its contribution is due to an expatriate rather than a British national who has always predominantly been the source of the movement’s contributions. And with its fiercely nihilistic finale, I could not help but make my own comparisons and ones in which I saw the film as Losey’s unhinged condemnation of certain power structures, mainly those of the film industry, and one he may have experienced his own master/servant relationship and like Hugo only to be met with his transgressions as a result of his exile due to prejudice and extremism.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

When a car bomb explodes on the American side of the U.S./Mexico border, Mexican drug enforcement agent Miguel Vargas begins his investigation, along with American police…

In 1943, Rudolf Hoss, commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, lives with his wife Hedwig and their five children in an idyllic home next to the camp. Hoss takes…

In this classic thriller, Hans Beckert, a serial killer who preys on children, becomes the focus of a massive Berlin police manhunt. Beckert’s heinous crimes…

Also known as the Kitchen Sink movement, was a transformative era in British cinema that emerged in the late 1950s and continued till the late 1960s. It was a period…

In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, until mid 1980s, a cinematic revolution unfolded in Hollywood that would forever change the landscape of the film industry. American New Wave…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…