slums of beverly hills review

film by Tamara Jenkins (1998)

The designation “lower middle class” always struck me as slightly comical, as seemingly contradictory as “The Flats of Beverly Hills.” Much like the (relatively) less affluent, and (significantly) less topographically flamboyant neighborhood some acres south of Beverly Hills Proper, it feels borne of insecurity, precarity, the puttering anguish of those not really “working class” but insecure enough to develop bizarre neuroses about restaurants with cloth napkins.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

April 03, 2025

The Abromowitz’s exist in this netherworld, forever doomed to exhausting, circular negotiations with what Jewish-Americans are supposed to be and the actual lived reality of a squabbling family unit trying to survive on used oldsmobile sales post-OPEC. It’s maddening, it’s bleakly funny, it’s Slums of Beverly Hills. Que the big band segues.

There are many great films about a young woman’s bildungsroman, but I’ve never seen one so deft about economic insecurity and how that intersects with First Sexual Experience, First Aborted Semi-Crush, First Bra Fitting. In the eyes of Vivian Abromowitz’s family, her body is no different from a prime sirloin at Sizzler or the square footage of their latest apartment; a class signifier, a valuable asset in The Grand Reclamation of Upward Mobility.

No matter what she wears, no matter how she presents herself, she’s signifying SUNSET TART or TORRANCE TRAILER TRASH or perhaps worst of all, SOME NEBULOUS YET TERRIFYING REPRESENTATION OF WHAT MAKES DAD AND BROTHER UNCOMFORTABLE. In 1976, for girls like Vivian, you can literally never win. Everything’s unbecoming.

These are, certainly, “broad” performances, but broad is not a synonym for “lazy.” Everyone is vigorously mainlining director Tamara Jenkins’ hyperspecific cadence of midcentury Jewish-American insecurity, and if you take issue with that, well, you may be an antisemite. These people reminded me so intensely of my in-laws I nearly had a panic attack. We’ve sailed right past the shock of recognition and swan dove into The Schmear of Doppelgangers. The Abromowitz’s are the Koskoff’s and the Koskoff’s are the Abromowitz’s. Same family, same shadows (Decibel readings equally dangerous to long term hearing). There are:

1) The Curmudgeonly Patriarch, perpetually angry and unhelpful in a pinch, prone to casual racism and sexually inappropriate comments alike, yet strangely lovable (Alan Arkin, baldly volcanic).

2) The Cut-Up Kid Brother, genuinely funny beyond his years, but inheriting far too much of The Curmudgeonly Patriarch’s reactionary worldview (David Krumholtz, smarmily pathetic).

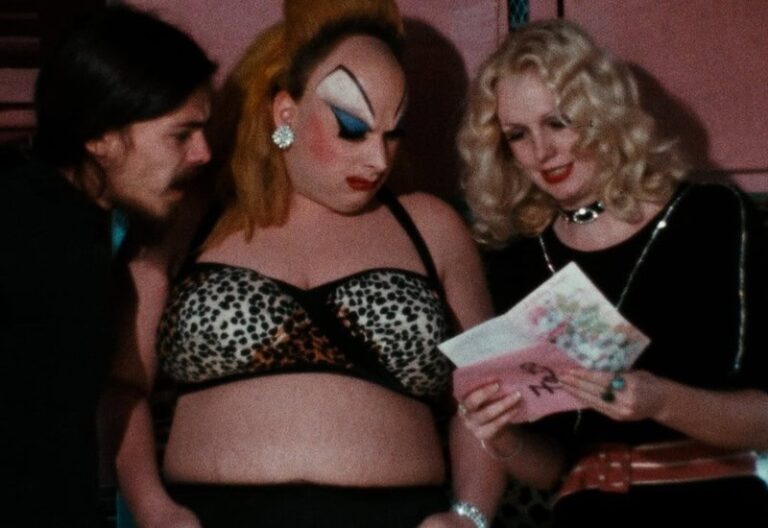

3) The Fallen J.A.P. Warrior Princess, derided by straight society as “shallow” or “ditzy,” or “a major liability to most Long Island roundabouts” but in all seriousness the most self-actualized person in the entire familial unit. (Marisa Tomei, responsible for 7/8ths of my sexual pathology).

4) The Burdened Child, ashamed of their family, prone to fits of self-destructive creativity, equally susceptible to self-immolation, longing for 18 so they can permanently sever any and all connection, and yet…can’t quite quit them. Someone smarter than me once called the patriarchal family unit “the most unbearable friends you’re not allowed to choose,” and I (along with Natasha Lyonne, bearing a sort of self-conscious moxie) embodied this character so fervently I nearly cried. I had a childhood analog in Vivian Abromowitz, in Mandy Koskoff. They’re the same person.

The folks who distributed this were Fox Searchlight; under no circumstances waltz into this expecting that brand’s Formica flavorings. Director Tamara Jenkins—criminally underused by Hollywood in the wake of this release—holds magical control over every inch of her autofiction. She blends a sinewy docu-realism with the Talismanic Time-Freezing Hyperfocus of Adolescent Drift. At times, I was tempted to saddle this with the label of “magical realism,” already a problematic term, if only because it keeps airport novelists in business.

I’ll say this: Jenkins captures the financially precarious adolescent experience—helped, in addition, by the immaculate 70’s Daymare Bric-a-Brac—with the confidence of a Roman centurion. It is insane to have a debut so tight, so self-assured in its visual imagination. Everything flows. There is no dead air, no fumbling about for purchase. Just Jenkins and Her Tragicomic Stucco Hotpot. It is incredibly refreshing that a film about Beverly Hills features neither hills nor postcard Pacific vistas; just dead leaves and a brassy-voiced broad bobbing in the motel pool.

Vivian has an ambiguous relationship—it’s almost a crush, perhaps more of a Practical Experimentation With Who’s Available, as was common for many of us back then—with Eliot Arenson, whose prime asset is being alluring in a discomforting way. Those beetle-brows bewitched me, the honeyed smarm reminded me; I knew this actor. I’d seen him in something. Where? Where? Oh my God, it’s Sean “and why are we graced with your presence?” Costigan from The Departed! The Fuckup Cousin to fuck up all cousins! The one who makes degrading remarks about Puerto Ricans while dealing drugs in the lowest-IQ ways possible! I fucking love this dude; he reminds me of my own cousins.

It is difficult to sell Eliot’s (Kevin Corrigan, transcendentally scumfuck) aura without sounding a rad ridiculous. OK, so he’s an aimless 70’s slacker, dealing ditchweed to fund his Charlie Manson obsession? And he wields his sub-Goldblumian rizz to score with girls who are (I was actually unsure as to Eliot’s age, but I clocked him around 17-19) inappropriately young for him? Damn son, have you ever visited a community college in Central Texas? But I digress; Aron, for all his queasy familiarity, his lazy charm, is alluring. That’s why he’s dangerous.

Kevin Corrigan’s performance is a study in Stress Tests Upon The Membrane of Comfort. He’s not off-putting enough to dismiss as irrevocably creepy, but he’s just persistent enough to raise more red flags than the Paris Commune. Vivian knows he’s a loser, she’s well aware that his Manson predilection is nothing but ephemeral male fixation; next summer he’ll get really into Moonies, perhaps get busted for dealing to nuns.

But he also Lives Next Door. He has a car. He’s pathetic in a compelling way. He could be a relatively painless way to cross off those Terrifying Teenage Firsts. When Vivian and Eliot have sex, Jenkins’ camera sails over them once, twice. It’s like flitting celluloid, slown down to several pans a second. Aron is the caliber of guy you perhaps owe an explanation, but not quite enough to make it particularly cinematic or compelling or even fully true.

Every Teenager Who Grew Up Financially Precarious—and I imagine this is far more people on this site who let on—achieves a kind of transcendence when they grow just adult enough to realize, “I can become strategic in my compromises. I can lie in comforting ways to authority figures. I can experience pleasure in ways which neither alienate buffoons nor draw their ire upon me. I may never Not Hate my family, but I can live with them.”

It’s extremely cool to Not Hate your family; at strange intervals I think I love them.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

Just out of jail, crumpled English archaeologist Arthur reconnects with his wayward crew of tombaroli accomplices – a happy-go-lucky collective of itinerant…

In the near future where emotions have become a threat, Gabrielle finally decides to purify her DNA in a machine that will immerse her in her past lives and rid her…

The film is set in the Broward and Dade Counties of Florida, between Miami and the Everglades (nicknamed “the River of Grass”). The story concerns a…

American eccentric cinema is a distinctive style of filmmaking that surfaced in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, characterized by its quirky characters, whimsical…

A cult film is a movie that builds a devoted following without achieving mainstream success or widespread critical praise at the time of its release. These films are…

Independent film, often called indie film, is produced outside the major studio system. Its roots can be traced back to the early 20th century, when filmmakers began seeking…