river of grass review

film by Kelly Reichardt (1994)

Florida seems embarrassed of itself. Sure, the other jug-hooter states commit embarrassing acts, but they have a sense of pride about it. They challenge you to loathe them. Florida, incredibly, just wants to be left alone. Our nation’s solitary peninsula, it juts into the Atlantic like a Priapic problem child.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

March 24, 2025

Its parentage is composed of regimes which no longer exist: The Mississippian Constellation, The Spanish Empire, The Seminole Nation, The Confederacy, Fulgencio’s Cuba, Somoza’s Nicaragua. A permanent latchkey state, it has never felt at home among the Contiguous 48; Florida Man has been permitted residency but denied citizenship.

Most people know, via her filmography, that Kelly Reichardt is a creature of the Pacific Northwest. Every subsequent film either takes place in Oregon or Montana. That she actually grew up in Hick Sprawl Miami-Dade, where her debut takes place, forced me to reconsider the woman; this is the most Reichardtian film and it’s the least, which I will fully untangle in a paragraph or nine.

Cozy (Lisa Bowman)—named for the Jazz drummer—tumbled out into a world of screendoor makeout sessions and Cop Dad Distancing and The Unbearable Weight of Familial Inertia. She is expected to become a Mother, as her Mother was before her – before Mom fled Cop Dad’s inability to party properly – as her mother was expected to, expected to, etc. She enjoyed making out and hanging out but motherhood always felt burdensome. Getting married felt likewise. She ended up doing both.

Lee Ray Harold (Larry Fessenden)—honoring the Southern Trifecta Naming Convention—is less sympathetic than Cozy because he’s stifled by laziness and not patriarchal-capitalist strictures. He lives with his grandmother and is essentially who Beavis would degenerate into if he were allowed to age outside cell animation. He has a mullet which is in severe danger of balding and is best friends with Steve Buscemi’s brother. He has a thing for guns. A lot of southern losers have a predilection for guns.

Cozy begins to self-actualize by transforming into a Robert Crumb caricature – no, that’s not quite right. Because she’s transforming for herself and not the pathetic fetish of a racist cartoonist. She slides into short shorts and a top my cousin Gabriella described as “slutty in a self-affirming, post-Sassy way.” Cozy is a 40-something mother of two. She looks stupendous. She looks unconquerable. Most importantly, she’s actively shifting the universe around her into Something Exciting. Florida is bereft of excitement.

Initial reviews of River of Grass were, to put it mildly, flummoxed. They could not make head nor tail of Reichardt’s Ode to Florida. In a state of desperation, they labeled it “Jarmuschian.” I find this appellation curious because while, yes, this film concerns society’s castoffs, it also does not care whether any of these characters are “good.” Jim Jarmusch has a neediness to confirm the goodness of his castoffs. No matter the film, no matter the socioeconomic/geographical context, he’s insistent that we will Warm Our Heart Cockles to These Lovable Losers.

Reichardt, no matter the film, does not care whether her characters are “good.” She is not concerned with the status of their goodness in The Soul Credit Rating System. She wants us to empathize with their life experience, but she does not need them to be salvageable. That is a crucial difference. To splay things out a bit, Reichardt is akin to Maxim Gorky (has a materialist critique of capitalism, uninterested in sentimentalizing characters) while Jarmusch is akin to Luchino Visconti (has a romantic’s frustration with capitalism and desperately wants you to love private property’s malcontents and/or fantasize about fucking them.)

Both approaches are—I am in a fit of bourgeoisie subjectivity, for I have just chugged seven non-alcoholic beers and a liter of kombucha—equally valid. I do think it’s interesting to point out the gender inversion, in that Jarmusch is the sap and Reichardt the hyperrealist.

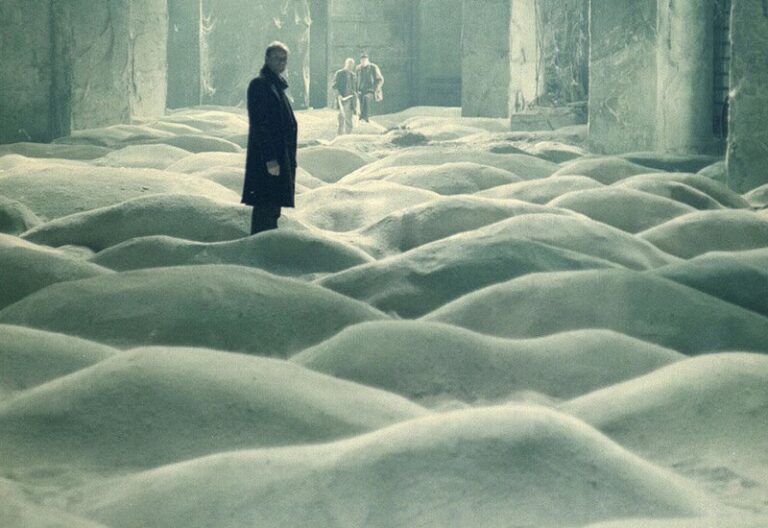

Well, Reichardt’s not fully languishing in the valley of the hyperreal. There is much surrealism in her Hick-Sprawl Miami-Dade. The film opens on B&W flashes of husbands slaughtered. Cop Dad loses his service revolver while pursuing a being who may or may not be corporeal. There are honkytonks, frequented by Fathers From Antecedent Time, which feel unreal because the bartender’s jokes are actually funny. There are Motel Six’s run by hardnosed transplants and haunted by dybbuks. Husbands are permeable and fathers may pursue, but boredom is inevitable. No human has ever outrun boredom.

This is not a film about Lovers on the Run. Cozy and Lee Ray Harold don’t love each other and the only “crime” they actually commit is tollway violation. Cozy and Lee Ray Harold aren’t lovers; they’re just two people, equally alienated from Hick-Sprawl Miami-Dade, who discover someone else equally lonely and stymied. They never, at any point, have sex. They never kiss. They never say “I love you.” They could be said—at most—to prefer the other’s company to braying hogs at the bathroom door. It would’ve been far simpler to make this Florida Badlands; Reichardt refuses.

Cozy kills Lee Ray Harold because he reneges on The Fantasy. The Fantasy is not a silly, ephemeral thing; it’s simply pretending there’s something more exciting around the corner. Most of us have acted violently when some asshole told us we had to endure 9-5 Good Government Bullshit with a grin. I certainly did growing up. I concocted elaborate fantasies. When I watched films I adored, I’d pretend I’d written them and “pipe-in” the approval of teachers and buddies who were not actually sitting with me. Whenever I felt exploited working as a bus boy or golf course attendant, I’d engage the Fantasy; pear-shaped families were working for me. Perhaps most tellingly, I’d re-write the dialogue of friends—in real time—into something more compelling for myself. I was the star of my own misery, and baby, the script was Oscar Worthy.

Funnily—or tellingly—I stopped all that when I seceded from My Parents’ House.

When Reichardt conjures up Hick-Sprawl Miami-Dade, it has the uneasy interstitial charms of being both hyperreal and surreal. Again, the critics didn’t know what to make of it. It seemed a contradiction in terms. But—if I may proffer the compromise of a 31-year-old ex-Fantasist simpleton—it’s that Florida is so fucking strange, so un-tethered from Corporeal Amerika, that both appellations apply at once. It is as shamefully mundane as perforating tin cans via stolen gun in full view of PROSECUTEURS WILL BE SHOT. It’s as dreamlogic absurd as suckling 4Loko from teats which may belong to some mother, somewhere, or maybe it’s just a Fellow Outlaw. I wouldn’t rightly know. I am passionately dedicated to squaring circles and dotting your Sanskrit prescriptions.

I just know I’m relieved to not have to choose anymore.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

A 1993 British black comedy drama film starring David Thewlis as Johnny, a loquacious intellectual, philosopher and conspiracy theorist. The film won several awards…

Miso lives from day to day by housekeeping. Cigarettes and whiskey are the two things that get her through the day. As cigarette prices and rent start to rise…

Following the everyday lives of a group of young theater performers from rural Fenyang, spanning the late 70s to the early 90s in the aftermath of China’s Cultural Revolution…

Independent film, often called indie film, is produced outside the major studio system. Its roots can be traced back to the early 20th century, when filmmakers began seeking…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…

American eccentric cinema is a distinctive style of filmmaking that surfaced in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, characterized by its quirky characters, whimsical…