salt of the earth review

film by Herbert J. Biberman (1954)

Beginning in the 1930s, Hollywood propagated its conservative approach of curbing subversive themes and suppressing ideas outside the status quo through censorship, employing the Motion Picture Production Code, also known as the Hays Code, named after Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA). Once a purveyor of free expression and controversy, reveling in the notoriety of films regarded as “indecent” and “filth,” the film industry became a bastion of conservative powers that left Tinseltown with an ultimatum. This inevitably changed laws that impacted storytelling and artistic expression by giving the industry the power to regulate creative material.

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

Jun 13, 2024

The Hays Code embodied an entirely new philosophy compared to that of Hollywood in the 1920s. Outlining an austere set of guidelines between 1934 and 1968, it enforced strict censorship over the content of any film released within the Motion Picture Association of America, forcing directors to abide by and stay within the parameters of what was deemed “acceptable.” Its creation pushed more radical and progressive ideas further into subversive realms with little or no representation of alternative perspectives, leaving a largely conservative white male American point of view as the sole voice, ideology, and representation on the silver screen.

Simultaneously, the rise of fascism loomed ever-increasing over the globe, erupting into WWII. The war aroused new cinema movements, including Neorealism, which originated in Italy and centered around the struggles of those opposing the Nazi war machine, surviving a post-WWII Europe through the portrayal of the underrepresented common individual—a movement with which Salt of the Earth shared some key factors.

From post-WWII America, a time when the government was becoming increasingly paranoid about the influence of communism, came 1954’s Salt of the Earth, a collaborative effort between Michael Wilson (writer), Paul Jarrico (producer), and Herbert J. Biberman (director), all of whom, at the time of the film’s production, were victims of the Hollywood blacklist. This made Salt of the Earth the only film created by currently blacklisted members of the industry, and one that inevitably suffered the same fate as its creators. Biberman was blacklisted and served six months in jail for refusing to answer questions from HUAC, becoming one of the Hollywood Ten, a group of individuals consisting of screenwriters, directors, and producers accused of injecting communist ideals into films. After invoking their First Amendment rights and refusing to answer questions about the details of their participation and political affiliations, they were charged with contempt of Congress and sentenced to jail time ranging from six months to a year. Paul Jarrico was blacklisted after being released from RKO under the authority of Howard Hughes and, like Biberman, refused to testify.

Michael Wilson, who suffered the same fate as Jarrico and Biberman, relocated to France and found work in the European film industry, similar to Joseph Losey, who relocated to London where he directed the British New Wave film “The Servant“. Also blacklisted and under the authority of Hughes at RKO, Wilson continued to write screenplays for Hollywood under pseudonyms or without any credits, including classics such as “The Bridge on the River Kwai,” “Lawrence of Arabia,” and “Planet of the Apes”. Jarrico and Biberman asked Wilson to write a script for their newly developed film company called The Independent Productions Corporation, making Salt of the Earth the only film released under the company name.

Salt of the Earth is a neorealist pro-labor film based on the true events of stateless New Mexican zinc miners who initially went on strike to demand safer work conditions but became a driving force of political activism and social change. Their fight for equality grew to include racial, gender, class, and economic rights they were currently being denied. The film tells the story of the struggles of union miners who were largely of Mexican ethnicity and who were left in bureaucratic limbo, neither being recognized as Americans nor Mexican nationals, having to fight for every inch of their basic human rights.

Centering around the unique narrative of the miners’ wives who discover a loophole allowing them to become picketers after the men are forced off the picket line through bureaucratic tactics, the film openly acknowledges a feminist point of view. It touches on our unconscious biases, revealing attempts to uphold the prejudices of misogyny while condemning those of racism and classism, and is a perfect example of how prejudice so often runs deeper than self-interest. It is a pensive display of self-awareness that consciously condemns double standards at a time when so many examples of inequality and injustice in cinema were accompanied by tone-deaf infractions of sexism and racism.

The film cast professional actors, some of whom were also blacklisted, and nonprofessionals, many of whom represented the roles they portrayed. Choosing to include authentic ethnic representation rather than whitewashing the characters to make them more palatable to a larger audience, the film represents a refusal to participate in the patterns of exclusion upheld by the same system that blacklisted the creative minds behind the film. This acts as a gesture of solidarity and support for diversity by any means possible.

The production experienced opposition from the Hollywood industry, including that of Howard Hughes, who participated in sowing dissent, sabotage, and supporting harassment during the film’s production, contributing to its blacklisting. Congressman Donald Jackson, supported by Hughes, spoke on the floor of Congress, claiming the film was a communist production. Rosaura Revueltas, the lead actress, had her passport and visa seized by immigration officials on set and was branded a communist, leading to her arrest and charge of entering the country illegally, even though she possessed proper documentation that granted her entry into the country. She voluntarily returned to Mexico instead of being forced.

As a result, Revueltas never finished her scenes, and the production had to use a double. The local paper in Silver City published an article suggesting those in Silver City not involved in the film forcibly remove those labeled as “communists,” intended to create further discord. The film crew received death threats from the local community, including some finding bullet holes in their cars, while others were harassed for years by the government after the film’s completion.

After the production finished, some of the locals who participated in the film were continually harassed, which led to some losing their homes to arson, although the local district attorney denied this. This resulted in a very limited release, burying the film into obscurity with only some international exposure. The film’s creators were denied any earnings by the U.S. government. Only later did Salt of the Earth develop a cult following through fringe groups and those interested in the arts outside the mainstream standard, including college campuses, arthouse collectives, and activist groups that have slowly gained momentum since the 1960s.

Hailed by Noam Chomsky and described as communist propaganda by Pauline Kael, Salt of the Earth is a subversive piece of guerrilla filmmaking that, 70 years later, remains a revolutionary piece of cinematic history and activism as well as a temperature reading of 1950s America during McCarthyism. It also remains one of the first sensitive representations of Mexican Americans and racial and gender inequality, a precursor to many social conversations still finding traction today and a reminder of the nation’s divisiveness.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

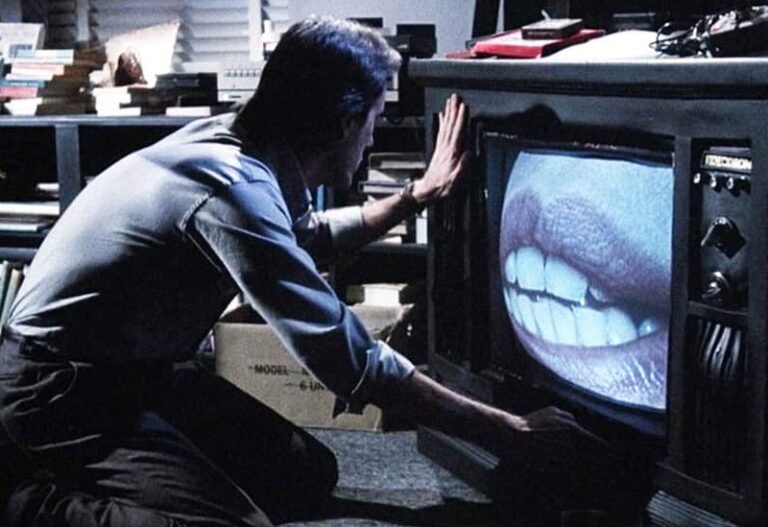

As the president of a trashy TV channel, Max Renn is desperate for new programming to attract viewers. When he happens upon “Videodrome,” a TV show dedicated…

When a car bomb explodes on the American side of the U.S./Mexico border, Mexican drug enforcement agent Miguel Vargas begins his investigation, along with American police…

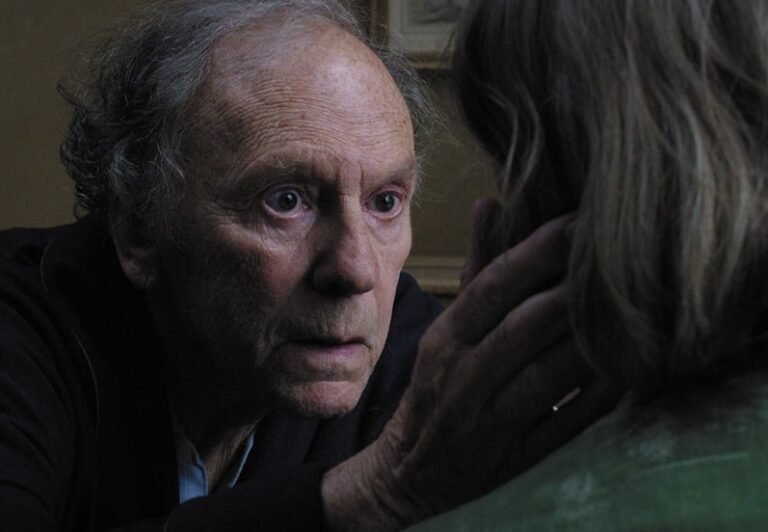

Georges and Anne are in their eighties. They are cultivated, retired music teachers. Their daughter, who is also a musician, lives abroad with her family. One day…

The studio system was a dominant force in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was characterized by a few major studios controlling all aspects of film production…

In the early 20th century, a cinematic revolution was brewing in the Soviet Union. A group of visionary filmmakers, collectively known as the Soviet Montage School, gathered…

Silent films, originating in the late 19th century, represent the foundation of modern cinema. Characterized by their lack of synchronized sound, these films relied on visual…