what is slow cinema?

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its contemporaries and the broader changes in the film industry that have shaped its trajectory.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

Early Influences

Slow cinema’s origins can be traced back to mid-20th century filmmakers who emphasized a contemplative approach to storytelling. Key figures like Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, and Andrei Tarkovsky laid the groundwork for this style with their focus on minimalism, long takes, and a deliberate pace. These directors, working in different cultural environments, contributed to a shared aesthetic that valued the passage of time, introspection, and the visual over the purely narrative.

Yasujiro Ozu: Films, such as “Tokyo Story” (1953), are known for their meticulous framing and focus on the subtleties of human relationships. His work often explores themes of family with a calm, unhurried narrative. Ozu’s distinctive style, now famous with the use of low camera angles and a lack of camera movement, draws viewers into a meditative state.

Robert Bresson: His ascetic style, characterized by casting of non-professional actors and minimalistic techniques, can be seen in films like “Au Hasard Balthazar” (1966). The focus on spiritual and existential themes contributes to the introspective nature of his films. Bresson’s approach to “pure cinema” stripped away unnecessary elements, leaving a stark, contemplative experience.

Andrei Tarkovsky: Tarkovsky’s films “Stalker” (1979) and “Solaris” (1972), are renowned for their philosophical depth and visual poetry. His use of long takes and a meditative tempo creates a highly immersive experience. Tarkovsky’s belief in the power of cinema to capture the flow of time and the spiritual essence of reality influenced a generation of filmmakers who aim to create films that transcend classical storytelling.

Characteristics of

Slow Cinema

Long takes: Extended, unbroken shots allow viewers to absorb the scene in real-time, creating a sense of immersion and contemplation. These shots typically emphasize the passage of time and the details within a scene. The use of long takes challenges conventional pacing and encourages viewers to engage with the film on a more reflective level.

Minimal dialogue: Dialogue is often sparse, with emphasis on visual storytelling and ambient sounds. This allows the audience to focus on the nuances of the characters’ actions and the environment. The reduction of dialogue places greater importance on non-verbal communication and the subtleties of performance.

Naturalistic pacing: The films reflect the natural rhythms of life, with scenes unfolding at a deliberate pace. By mirroring the flow of real time, slow cinema creates a sense of authenticity that allows audiences to experience the events as if they were happening in the present moment.

Visual and auditory focus: Slow cinema uses visual and auditory elements to create a sense of mood and place. The careful composition of each frame and the use of soundscapes enhance the sensory experience of the film.

Themes of time and existence: It frequently explores existential themes, the passage of time, and the minutiae of daily life. These themes are conveyed through the film’s slow pacing and visual style.

Evolution in the

Late 20th Century

In the latter half of the 20th century, directors like Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and Bela Tarr further developed slow cinema, pushing the boundaries of narrative structure and visual composition. These filmmakers built upon the foundations laid by their predecessors, exploring new thematic and stylistic territories while maintaining the core principles of slow cinema.

Chantal Akerman: Akerman’s “Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles” (1975) is a seminal work in slow cinema, depicting the repetitive routine of a woman’s life, while emphasizing the passage of time and the monotony of domestic tasks. Her focus on the minutiae of life and the rhythms of mundane activities challenges viewers to find meaning and beauty in the ordinary.

Theo Angelopoulos: Angelopoulos explored themes of history, memory, and exile in his films, example is “The Travelling Players” (1975). The use of long, unbroken shots and a slow narrative pace highlights the epic nature of his storytelling. Angelopoulos’ films often span decades and continents, weaving personal and political histories into a tapestry that reflects the complexity of human experience.

Bela Tarr: Films as “Satantango” (1994) and “The Turin Horse” (2011) are characterized by their bleak, atmospheric visuals and long takes. His work delves into themes of despair and existential contemplation. Tarr’s unique visual style, marked by fluid camera movements and composed shots, creates a sense of immersion that draws viewers into the oppressive worlds he portrays.

Contemporary Slow Cinema

In the 21st century, slow cinema continues to thrive, with Asian directors like Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tsai Ming-liang, and Lav Diaz contributing to the genre. These filmmakers bring diverse cultural perspectives and innovative approache to slow cinema.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Weerasethakul’s films, such as “Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives” (2010), blend elements of folklore, spirituality, and slow-paced storytelling, while exploring themes of memory and the supernatural. Weerasethakul’s unique narrative style seamlessly integrates dreamlike sequences and fragmented timelines.

Tsai Ming-liang: His meditative and visually rich films, as “Goodbye, Dragon Inn” (2003), explore urban alienation and human connection. They feature long, static shots that capture the emptiness and isolation of modern urban life, emphasizing the characters’ emotional and physical distance from each other.

Lav Diaz: Diaz’s epic-length films delve into Philippine history and society with a slow, deliberate narrative style. Extended runtimes of his films and immersive storytelling techniques allow him to explore the historical and sociopolitical context of his characters’ lives in great detail, offering a nuanced portrayal of contemporary Philippine society.

Legacy and Influence

of Slow Cinema

While slow cinema may not dominate mainstream film, it has carved out a significant niche in the industry. Its influence can be seen in various contemporary works that embrace elements of the style. Slow cinema continues to evolve, finding new expressions and audiences in the digital age. Streaming platforms and film festivals have significantly helped reach global viewers, ensuring its ongoing presence and impact.

The style remains vital and evolving, offering an alternative to the fast-paced, plot-driven films that dominate mainstream. Its emphasis on contemplation, visual beauty, and existential themes continues to resonate and inspire audiences and filmmakers alike.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

Taiwan New Wave, also known as Taiwan New Cinema, was a film movement that flourished during the 1980s and 1990s. It gained international acclaim for its exploration of complex…

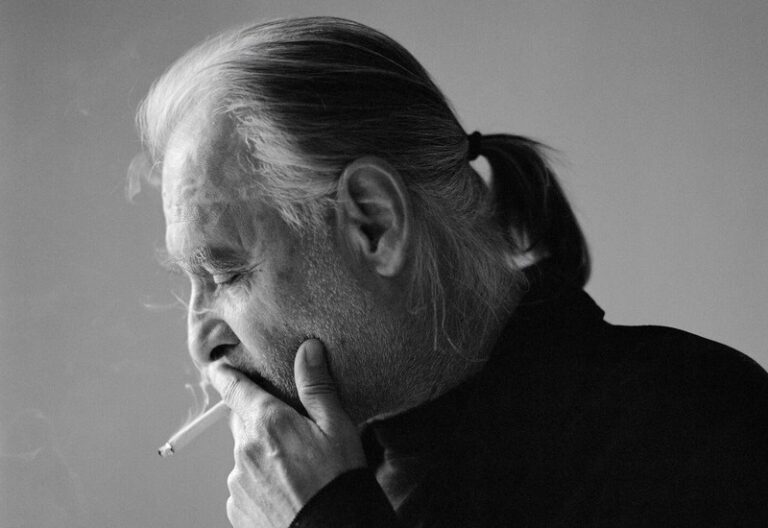

Béla Tarr is one of the most respected Hungarian directors and is also a pivotal figure in the genre that is “slow cinema” which is a style that prioritises stillness, long takes, and…

In the late 19th century, a young Danish priest travels to a remote part of Iceland to build a church and photograph its people. But the deeper he goes into the unforgiving…

Indian cinema is synonymous with Bollywood, known for its vibrant song and dance sequences and blockbuster entertainers. However, beneath the glitz and glamour…

Letterboxing in film refers to the practice of presenting widescreen content on a standard-width (usually 4:3) screen by placing black bars above and below the image…

Animation is an ever-evolving art form that has enchanted audiences for more than a century. From the earliest experiments in motion pictures to the cutting-edge CGI of…