understanding letterboxing in film

Letterboxing in film refers to the practice of presenting widescreen content on a standard-width (usually 4:3) screen by placing black bars above and below the image. This technique preserves the original aspect ratio of the film, ensuring viewers can see the entire frame as intended by the filmmakers.

Historical Context

Letterboxing emerged as a solution to the challenges posed by different aspect ratios between theatrical films and home viewing formats. Early cinema and television used the 4:3 aspect ratio, known as the Academy ratio. However, in the 1950s, filmmakers began experimenting with wider aspect ratios, such as CinemaScope (2.35:1) and VistaVision (1.85:1).

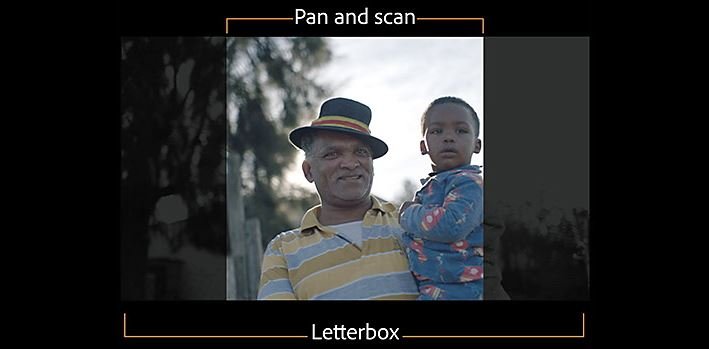

With the introduction of home video formats like VHS and Betamax in the 1970s and 1980s, films became accessible for home viewing, but televisions still adhered to the 4:3 aspect ratio. Initially, the “pan and scan” technique was used, cropping widescreen images to fit 4:3 screens, but this usually resulted in significant portions of the frame being lost. To address this, letterboxing was introduced, adding black bars to the top and bottom of the screen to display the entire width of the widescreen image on a 4:3 screen.

Technical Aspects

Letterboxing involves adding black bars, or “mattes,” to the top and bottom of the screen to maintain the film’s original aspect ratio. This ensures that a widescreen film, such as one with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio, is fully visible across the width of a 4:3 screen, with black bars occupying the unused space.

While this method preserves the full width of the image, it does reduce the visible height of the picture due to the black bars. This can occasionally give the impression of a loss in vertical resolution, but the overall image integrity is kept intact. The size of the black bars varies with different aspect ratios. For instance, a film with a 1.85:1 aspect ratio will have smaller black bars compared to a film with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio when displayed on a 4:3 screen.

Comparison with Other Techniques

Pan and Scan: This technique involves cropping the widescreen image to fit the 4:3 screen, focusing on the most important part of the scene. While this avoids the black bars, it often results in significant portions of the image being lost, altering the director’s intended composition and potentially losing important visual information.

Pillarboxing: The opposite of letterboxing, pillarboxing is used when fitting a narrower image, such as a 4:3 aspect ratio, onto a wider screen like 16:9. This results in vertical black bars on either side of the image.

Windowboxing: A combination of letterboxing and pillarboxing, windowboxing occurs when both vertical and horizontal bars are present, used when displaying an image that is both narrower and shorter than the display screen.

Impact on Viewing Experience

Letterboxing maintains the director’s intended composition, ensuring that the viewers experience the film as it was originally presented in theaters. While some viewers may find the black bars distracting, they become less noticeable over time, allowing for a more authentic viewing experience. Modern widescreen TVs (16:9) have minimized the use of letterboxing, but it remains relevant for ultrawide content. With the proliferation of widescreen TVs, letterboxing has become less prevalent for most contemporary content. However, it is still commonly used for:

Classic films: Older films originally shot in widescreen formats often use letterboxing when presented on modern screens to preserve their original aspect ratio.

Ultrawide formats: Films and content shot in ultrawide formats (e.g., 2.35:1) will use letterboxing even on 16:9 screens.

Streaming services: Platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and others use letterboxing to ensure that content is viewed as intended, regardless of the device’s screen ratio.

Contemporary Use and Significance

The 1990s and early 2000s saw advancements in digital technology and the adoption of DVD and Blu-ray formats, which offered higher resolution and better quality. Letterboxing became standard for DVDs, preserving the original aspect ratios of films. Around the same time, widescreen televisions with a 16:9 aspect ratio began to replace 4:3 models, reducing the need for letterboxing. However, films shot in ultra-widescreen formats still required letterboxing on 16:9 screens.

Filmmakers and content creators alike continue to explore various aspect ratios to enhance their narratives. Today, letterboxing is less about overcoming technological limitations and more about preserving artistic intent. It ensures that the visual storytelling created by filmmakers is accurately conveyed, regardless of the viewing platform.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking techniques and cinema history.

Cinematography is the art and craft of capturing visual images for film or digital media. It involves the use of cameras, lighting, composition, and movement to tell…

Film production is the process of creating a film from its initial concept to the final product. It involves numerous stages, each requiring a collaboration of…

Silent films trace their origins to the late 19th century when inventors like Thomas Edison and the Lumiere brothers pioneered motion picture technology…

Georges and Anne are in their eighties. They are cultivated, retired music teachers. Their daughter, who is also a musician, lives abroad with her family. One day…

Film noir emerged in the early 1940s as a distinctive style within American cinema, marked by its dark, moody aesthetics and cynical narratives. The term “film noir”…

In a bustling Mexican household, seven-year-old Sol is swept up in a whirlwind of preparations for the birthday party for her father, Tona, led by her mother, aunts…