funny games review

film by Michael Haneke (1997)

“What do you think? You are on their side, aren’t you?”

Review by: Max Palmer | Filed Under: Film Reviews

December 01, 2025

Michael Haneke’s Funny Games (1997) has built a reputation as a difficult and unsettling experience, but its real strength lies in how quietly it builds its argument. The film places the viewer in an awkward position, asking them to consider their own expectations of violence in cinema without turning that idea into a lecture. Haneke shapes the film around questions rather than answers, and the result is a thriller that gradually reveals how carefully controlled it really is.

The 1997 version works better than the shot-for-shot 2007 remake largely because of its unremarkable visual style. The house, the countryside and the characters feel familiar, almost anonymous. Nothing about the setting suggests anything dramatic or theatrical. The flat colours and natural lighting give the impression of a place that could belong to anyone. This plainness is deliberate. As the film becomes stranger and more self-aware, the contrast between style and intention grows more uncomfortable.

The story is simple. A family arrive at their holiday home and are approached by two young men dressed in white. Their politeness seems slightly off, but the tension comes from how long everyone stays within the rules of social niceness. The mother tries to be patient, the father tries to be reasonable, and the son tries to understand. The two visitors exploit this politeness slowly and deliberately. Haneke avoids shocks or dramatic escalation. The sense of dread builds from tiny interruptions rather than obvious threats, and the shift from odd behaviour to genuine danger is almost invisible.

The opening credits prepare the viewer for this distortion. Classical music plays as the family drive through the countryside, but the soundtrack suddenly cuts to the violent thrash-metal track “Bonehead” by Naked City. The shift is jarring enough to unsettle even before the narrative begins. Haneke seems to be signalling that the film will not follow the emotional cues the viewer expects. The imagery and the sound do not match, and neither will the comfort of the setting and the events that follow.

One of the most notable choices is the refusal to show violence directly. The film avoids graphic depiction and instead focuses on the emotional responses of the characters after the violence has occurred. This often results in long, uninterrupted shots where nothing appears to happen, yet the atmosphere becomes almost suffocating. One static shot, in particular, lasts several minutes and forces the viewer to sit with the aftermath of an unseen event. The lack of action creates more tension than any depiction could have, and the stillness becomes a central part of the film’s rhythm.

The fourth wall breaks shape the film in a quieter but equally important way. Paul glances at the camera early on, as if checking whether we are following his logic. These glances grow more pointed as the film progresses. Eventually he begins addressing the viewer directly, and the tone of these moments is calm, almost casual. He behaves as if he is letting the viewer in on a secret rather than disrupting the story. This approach works because the rest of the film maintains such a naturalistic tone. When the illusion is interrupted, it feels less like a stylistic flourish and more like a quiet accusation.

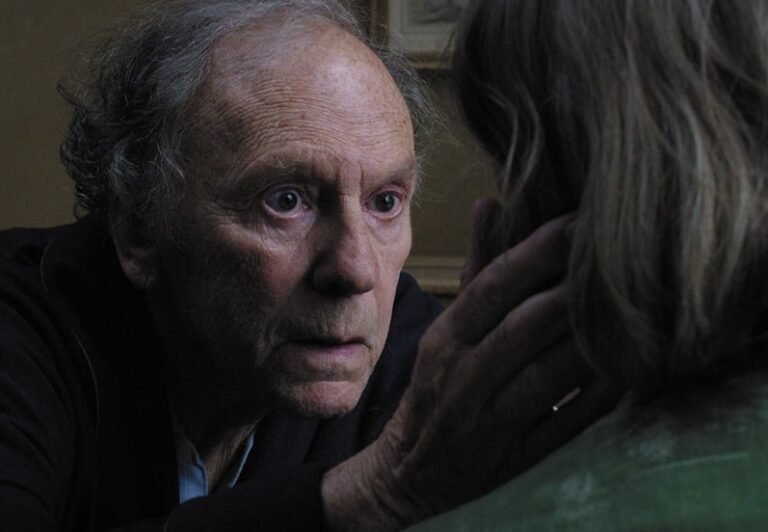

The performances anchor this effect. Susanne Lothar and Ulrich Mühe play the parents with a sense of disbelief that grows slowly into fatigue. Their reactions are small, restrained and believable. They do not behave like typical thriller protagonists who resourcefully fight back. Instead, they show confusion, frustration and moments of hesitation that feel very real. Arno Frisch’s portrayal of Paul is equally controlled.

He delivers his lines with a politeness that sounds genuine at first, before gradually taking on a more unsettling edge. His smiles are slight and his gestures are simple, which makes his confidence all the more disturbing. He never seems rushed or angry. He behaves like someone who has already decided how everything will unfold.

Analytically, the film functions as both a narrative and a study of viewer expectation. Haneke removes the usual cues that guide audiences through thrillers. There is no dramatic score, no heightened tension through editing and no clear structure that leads to hope or resolution. The viewer is left to navigate the events without the usual support systems, which exposes how often thrillers shape our emotions by following predictable patterns. Moments that would normally provide relief or catharsis are absent. Instead, the story moves forward with an unsettling calmness.

The film often lingers on mundane actions, and these moments create more unease than any violent set piece. Characters boil water, tidy objects or stare into space. The camera watches these actions with the same patience it applies to scenes of fear, which blurs the line between normal behaviour and danger. Haneke creates a rhythm that feels off balance, where the simplest activities carry tension because of what they follow or what they may lead to. This approach gives the film a sense of realism that keeps the viewer on edge.

Visually the film is defined by stillness and clarity. The camera rarely moves, and when it does, the movements are slow and deliberate. This minimalism reinforces the feeling that nothing is being exaggerated or manipulated for dramatic effect. The lack of music in key scenes adds to this quietness. Without the usual emotional indicators, the viewer must rely solely on the behaviour of the characters, which can be uncomfortable when those characters themselves are uncertain or frightened.

Some viewers may find the film too distant or controlled. The characters do not always express strong emotions, and the film does not offer a sense of closure. However, this restraint serves the film’s larger purpose. The structure, tone and performances all work together to question how stories about violence typically function and why we expect certain outcomes. The discomfort is part of the examination.

Overall, Funny Games remains one of Michael Haneke’s most carefully constructed works. It uses familiar elements of the home invasion genre but reshapes them into something far more analytical. The plain visuals, measured performances and self-aware structure combine to create a film that leaves a lasting impression not through shocks or spectacle, but through precise control. It is a demanding watch, but also a compelling one, and its quiet intensity continues to resonate long after the credits end.

Author

Reviewed by Max Palmer. Based in North Wales, Max has had an admiration for films ever since he got Pinnochio on DVD for his third birthday, since then he has grown to be a fan of anything and everything from David Lynch to Hayao Miyazaki. However his heart has a special place for anything shocking and underground.

Bruno Stroszek is released from prison and warned to stop drinking. He has few skills and fewer expectations: with a glockenspiel and an accordion he ekes out a living…

Georges and Anne are in their eighties. They are cultivated, retired music teachers. Their daughter, who is also a musician, lives abroad with her family. One day…

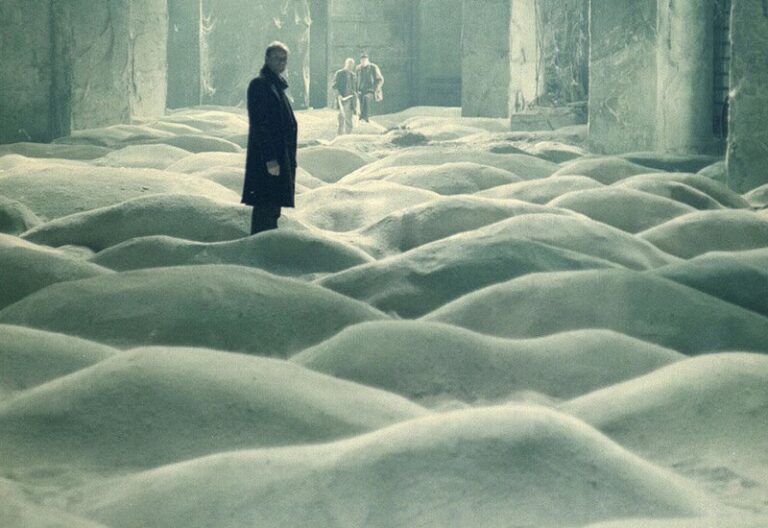

In 1943, Rudolf Hoss, commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, lives with his wife Hedwig and their five children in an idyllic home next to the camp. Hoss takes…

Bleak, unflinching, and thought-provoking are just a few words often used to describe Austrian born auteur Michael Haneke who is known for challenging audiences…

New German Cinema or Neuer Deutscher Film, is a film movement that started in the late 1960s, and thrived throughout the 1970s and 1980s. It represents a significant turning point…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…