the complete history of hollywood

The name “Hollywood” was once just a real estate gimmick, stamped on a patch of land at the edge of Los Angeles in the early 1900s. Within a decade, though, it had become shorthand for the entire American film industry. What drew the first filmmakers west was not glamour or legend but practical needs: a lot of sunshine, varied landscapes, and distance from Edison’s patent lawyers back east. The dream factory came later. Out of makeshift studios and rented barns grew an industry that learned quickly how to turn light and celluloid into power, wealth, and influence.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

The Early Days: Silent Films and the Birth of a Dream

When filmmakers first began experimenting in the late 19th century, few could have predicted how quickly (and massively) cinema would evolve. In the early 1900s, the American film industry was centered in New York and New Jersey, close to inventors like Thomas Edison.

However, the strict patent controls Edison held over film technology drove many independent filmmakers westward, seeking freedom from lawsuits and sunny weather that allowed year-round shooting. They landed in Southern California, specifically in a small agricultural community called Hollywood. But how did Hollywood get its iconic name?

It dates back to the 1880s. Real estate developer H.J. Whitley is often credited with coining it after hearing the word from a man he met while traveling through the area. He liked the sound and registered it, combining “holly,” the plant, with “wood,” giving the place an idyllic, almost pastoral identity that contrasted with the growing bustle of Los Angeles.

By 1910, studios such as the Nestor Company had already set up shop. Soon after, silent shorts were being shot in makeshift studios, and by the 1920s Hollywood had transformed into the movie capital of the world.

The silent era produced its first international stars: Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Buster Keaton, and Rudolph Valentino. Directors like D.W. Griffith revolutionized narrative cinema with films such as “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), a technically groundbreaking but controversial film, to say the least. Meanwhile, early comedies with Chaplin or Harold Lloyd showed that cinema could speak a universal language.

Silent films had orchestral accompaniment in theaters, and intertitles provided dialogue or narration. Yet even without spoken words, the emotional power of the medium was undeniable. By the mid-1920s, Hollywood was no longer an experiment. It was an empire.

The Arrival of Sound: A New Era in Storytelling

The late 1920s brought one of the most dramatic shifts in film history: synchronized sound. The “Jazz Singer” (1927) is often credited as the first “talkie,” as its success marked the end of the silent era. Studios scrambled to adapt, building soundstages and investing in new technology. Some silent stars struggled to transition, their voices not matching their screen personas, while others flourished.

Sound changed not just the technical side of filmmaking but also storytelling itself. Dialogue-heavy scripts became popular, and musicals exploded in the 1930s as audiences marveled at the novelty of hearing music on screen. Genres that had struggled in silence, such as gangster films, thrived with the arrival of talkies.

The early years of sound also gave rise to what is now called the Pre-Code era, roughly 1929 to 1934, before strict enforcement of the Production Code. Films from this period often shocked contemporary audiences with their frank depictions of sexuality, crime, and moral ambiguity. Stars like Barbara Stanwyck, Mae West, and James Cagney headlined stories that pushed boundaries with risqué dialogue and unapologetic portrayals of vice.

This creative freedom came to an abrupt end in 1934, when mounting pressure from religious groups and conservative voices led to the strict enforcement of the Hays Code. From then on, Hollywood operated under a set of moral guidelines that dictated what could and could not be shown on screen, shaping the tone and themes of American cinema for decades.

This period also cemented the rise of the “Big Five” studios: MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO. Along with Universal and Columbia, these companies created what became known as the studio system.

The Golden Age of Hollywood

From the 1930s to the 1950s, Hollywood experienced what many call its Golden Age. The studio system controlled nearly every aspect of filmmaking. Actors were signed to long-term contracts, directors were assigned projects, and studios owned both production and distribution channels.

During this time, genres flourished. Musicals such as “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952), sweeping historical epics like “Gone with the Wind” (1939), screwball comedies starring Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, and noir films filled with shadows and moral ambiguity all defined the era.

World War II also left its mark. Hollywood produced both patriotic propaganda and escapist entertainment to boost morale. Stars like Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in “Casablanca” (1942) became symbols of resilience and romance in turbulent times.

The Golden Age also cemented the idea of the movie star as cultural royalty. Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, and Elizabeth Taylor were more than just actors; they were larger-than-life icons. Cinema became central to American identity.

Challenges to the Studio System

As powerful as the studio system was, it began to unravel in the post-war years. The 1948 Paramount Decree forced major studios to sell their theater chains, breaking their vertical monopolies. Television’s rise in the 1950s provided a new form of home entertainment that competed directly with cinema.

In response, Hollywood sought to differentiate itself with spectacle. Widescreen formats like Cinemascope, 3D experiments, and big-budget epics such as “Ben-Hur” (1959) tried to lure audiences away from their living rooms. At the same time, independent production grew, giving directors more creative control and breaking the rigid studio contract system.

The Hollywood Ten

and the Blacklist

In the late 1940s, Hollywood entered one of its most turbulent periods with the rise of the Red Scare. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) accused the film industry of harboring communist sympathizers and summoned writers, directors, and actors to testify.

Ten screenwriters and directors, later called the Hollywood Ten, refused to cooperate, citing their constitutional rights. They were convicted of contempt of Congress, jailed, and soon after blacklisted by the major studios. The blacklist quickly expanded, shutting hundreds of artists out of work and forcing many to write under pseudonyms or leave the country altogether.

Under this climate of fear, studios avoided political subjects and turned instead to safer, escapist genres. At the same time, the blacklist fractured Hollywood itself: some cooperated with HUAC while others defended their colleagues.

The blacklist only began to break down in the 1960s, when Dalton Trumbo was publicly credited for “Exodus” and “Spartacus.” Though the era eventually ended, it left lasting scars on the industry and remains a stark reminder of how political pressures can shape and silence art.

The New Hollywood

Movement

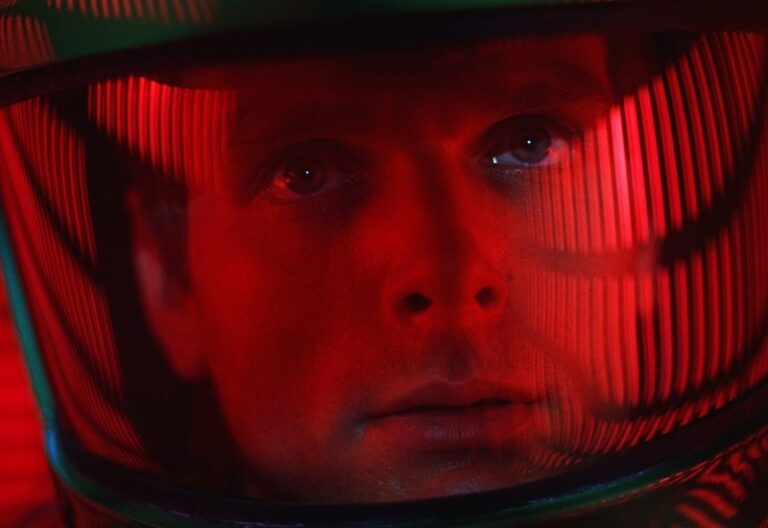

The 1960s and 1970s marked another radical transformation, as younger generation of filmmakers emerged. Influenced by European cinema, particularly the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism, and a cultural shift of Counter Culture, these directors wanted to achieve greater artistic freedom and realism.

The Hays Code, which had enforced moral guidelines since the 1930s, was replaced in 1968 by the MPAA rating system, which allowed for more explicit content and gave directors room to explore taboo subjects.

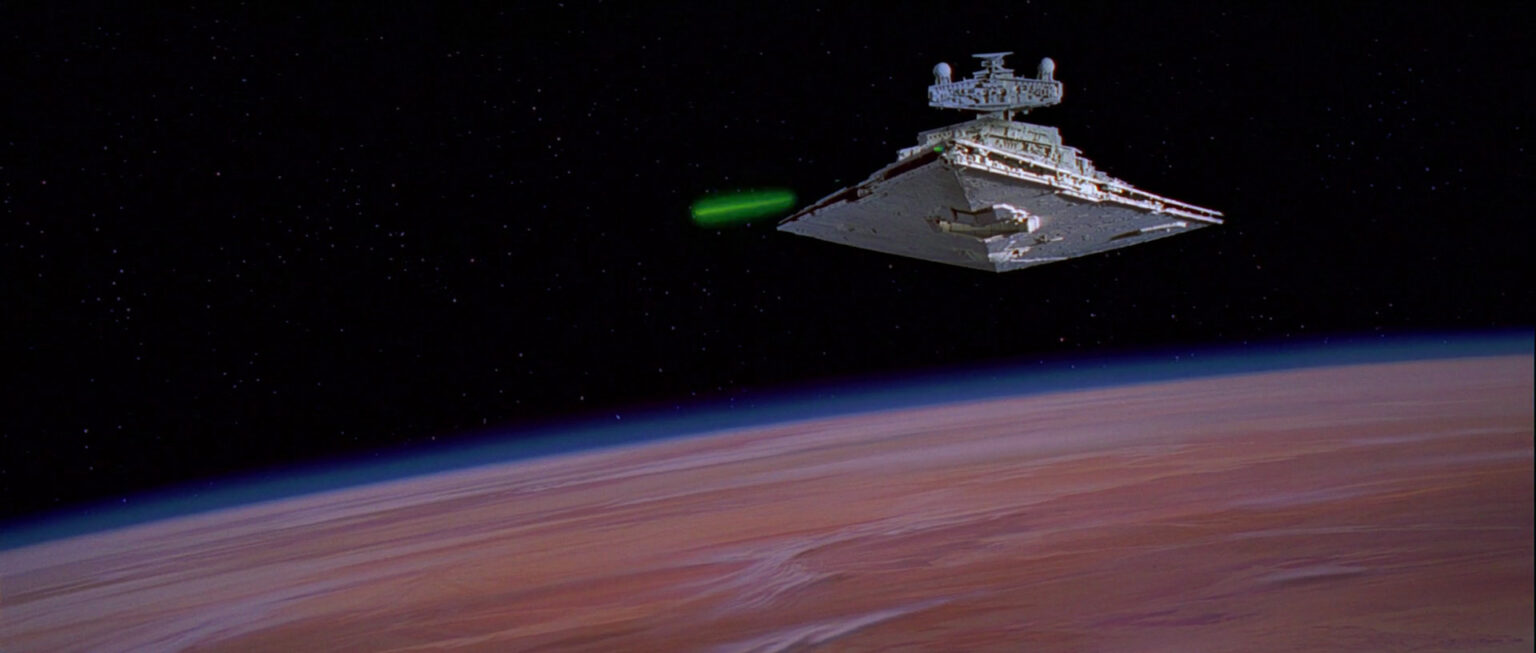

New Hollywood, or American New Wave, brought us groundbreaking and important films like “Easy Rider” (1969), which captured the counterculture spirit, and “The Godfather” (1972), which redefined crime dramas. Blockbuster culture also emerged during this era. “Jaws” (1975) and “Star Wars” (1977) introduced the concept of the summer blockbuster, shifting the industry toward high-concept, wide-release films that dominated the box office.

Hollywood in the 1980s and 1990s: Franchises and Globalization

By the 1980s, Hollywood had fully embraced the blockbuster model. Studios prioritized big-budget films with mass appeal, heavy marketing, and merchandising potential. Action stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone dominated, while franchises such as “Indiana Jones and Back to the Future” captivated audiences worldwide.

Technology again played a key role. The rise of VHS tapes and home video opened new revenue streams. Audiences could now rewatch films at home, and cult classics like “The Evil Dead” (1981) found new life outside theaters.

The 1990s brought digital innovation. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) transformed visual storytelling, as seen in “Jurassic Park” (1993) and “Toy Story” (1995), the first fully computer-animated feature. Hollywood also became increasingly global, with international markets influencing casting, storylines, and box office expectations.

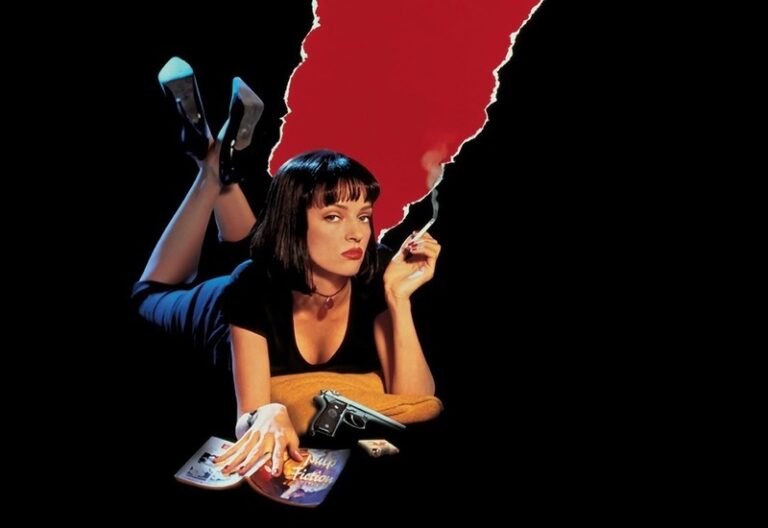

Independent cinema found a renaissance as well. Directors like Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers achieved great success outside mainstream, proving that smaller films could gain both critical acclaim and commercial success.

The 2000s to Today: Franchises, Streaming, and the Future

In the 2000s, the franchise model became Hollywood’s dominant strategy. Superhero films, particularly those from Marvel and DC, transformed the box office. The Marvel Cinematic Universe, beginning with “Iron Man” (2008), created an interconnected storytelling model that reshaped modern cinema.

At the same time, technological leaps continued. High-definition cameras, motion capture, and advanced CGI expanded what was possible. Peter Jackson’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy (2001–2003) showcased both technical mastery and epic storytelling, while James Cameron’s “Avatar” (2009) pushed 3D technology to new limits.

The rise of streaming platforms in the 2010s marked perhaps the biggest disruption since television. Netflix, once a DVD rental service, began producing original films and series. Other platforms such as Amazon Prime Video, Disney+, and Apple TV+ quickly followed.

Streaming has blurred the line between cinema and television, offering filmmakers creative freedom while also sparking debates about the theatrical experience. Several films, like “Roma” (2018) and “The Irishman” (2019) premiered on streaming but still garnered critical acclaim and Academy Award nominations.

Cultural Shifts

and Criticisms

While Hollywood has remained a cultural powerhouse, it has not been without controversy. Representation, diversity, and labor disputes have been ongoing challenges. Movements like #OscarsSoWhite highlighted the lack of inclusion in awards recognition, while #MeToo exposed systemic abuses of power within the industry.

Audiences are also increasingly critical of Hollywood’s reliance on sequels, remakes, and franchises. Some argue that risk-taking and originality have been overshadowed by formulaic storytelling designed for global box office appeal.

The history of Hollywood is a story of constant transformation. What has remained consistent is the power of storytelling. Audiences return to Hollywood films not only for spectacle but also for the emotions, dreams, and shared experiences they create. As the industry continues to evolve, Hollywood’s history reminds us that cinema is never static.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

The studio system was a dominant force in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was characterized by a few major studios controlling all aspects of film production…

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…

In the early 20th century, a cinematic revolution was brewing in the Soviet Union. A group of visionary filmmakers, collectively known as the Soviet Montage School, gathered…

Film criticism is an essential part of cinema, serving as a bridge between filmmakers and audiences. It focuses on analyzing, evaluating, and interpreting films, while providing…

Postmodernist film emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, rooted in the broader cultural and philosophical movement of postmodernism. It started as a reaction to the…

Juxtaposition is a powerful storytelling technique where two or more contrasting elements are placed side by side to highlight their differences or to create a new, often more…