polish film school

est. 1955 – 1963

The Polish Film School, also known as the Polish New Wave, is an influential film movement that originated in the countries post-World War II era. It stands today as a beacon of creativity and intellectual exploration of cinema as it influenced numerous Eastern European movements.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Movements

Origins of the Polish Film School

The Polish Film School emerged in the mid-1950s during a period of political and cultural shift in Poland, following the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in 1953. In the years immediately preceding, Poland, like much of Eastern Europe, was subject to strict censorship and ideological control by the communist government. Socialist Realism dominated the cultural landscape, dictating that art must promote the ideals of the state.

However, the period of liberalization that followed Stalin’s death, particularly under the leadership of Poland’s First Secretary Wladyslaw Gomulka, allowed for greater artistic freedom and opened the door for more nuanced, critical, and personal forms of expression in film. Despite the ongoing political control, the relative openness of the mid-1950s and 1960s allowed filmmakers to create films that would resonate with Polish audiences and gain recognition internationally, making the Polish Film School one of the first and most significant movements in Eastern European cinema.

The movement developed within the newly founded Lodz Film School, which had become a hub for young filmmakers eager to explore new cinematic techniques and push the boundaries of Polish cinema by addressing themes related to Poland’s complex history, particularly its experiences during World War II. Inspired by the works of Italian Neorealism, these filmmakers, many of whom had lived through the war themselves, used cinema to showcase the personal and collective traumas of the Polish people, offering a new perspective on history that contrasted with the official state narratives. The emphasis on real locations, ordinary people, and the harsh realities of war found a natural fit within the framework of the Polish Film School, further shaping its development.

Characteristics of the Polish Film School

The movement embraced realism, portraying the harsh and often grim realities of life in post-war Poland, emphasizing authentic locations, non-professional actors, and a raw approach to storytelling.

Symbolism and allegory played a significant role in the movement’s storytelling, as filmmakers used metaphorical narratives to convey deeper meanings. This symbolic depth added layers of interpretation to their works. The Polish Film School was characterized by its intellectualism, delving into complex themes, including moral dilemmas and existentialism, using cinema as a medium for further philosophical exploration.

The films of the Polish Film School frequently served as a vehicle for social and political commentary. Filmmakers depicted the complexities of life under communism, critiquing the oppressive nature of the regime and its impact on individuals. Their narratives provided a window into the human cost of political ideologies.

The films of this era showcased an innovative visual style. Cinematographers like Slawomir Idziak and Witold Sobocinski experimented with cinematography, using techniques such as deep focus, chiaroscuro lighting (low and high-contrast lighting, which creates areas of light and dark in films), and unconventional camera angles to create visually stunning compositions.

Important Filmmakers and Their Works

Regarded as the leading figure of the Polish Film School movement, Andrzej Wajda’s films like “Ashes and Diamonds” (1958) and Golden Palm winner “Man of Marble” (1977) are celebrated for their artistic depth and political engagement. Wajda received an honorary Academy Award, Golden Lion, and Golden Bear for his contributions to world cinema, which was a testament to the international recognition of the movement.

Andrzej Munk’s films often exhibited a keen interest in social and political themes. He gained international acclaim for his satirical war film “Eroica” (1957), which offered a unique perspective on heroism and the absurdity of war.

Although he gained international fame with films like “Rosemary’s Baby” and later “Chinatown,” Roman Polanski had his beginnings in Poland. His early work, including “Knife in the Water” (1962), showed his talent for psychological thrillers and his contribution to the movement.

Legacy of the Polish Film School

A testament to the resilience of artistic expression in challenging political contexts, the Polish Film School remains an essential chapter in the history of world cinema. Through its intellectualism, symbolism, and innovation, it not only challenged the conventions of its time but also pushed the boundaries of cinematic storytelling. Its legacy can be seen in the works of masterful directors like Krzysztof Kieslowski, and in contemporary Polish cinema, where directors like Pawel Pawlikowski and Agnieszka Holland continue the tradition of intellectual depth and philosophical exploration.

The movements impact transcends its borders. It laid the foundation for the exploration of cinema as an art form, while influencing subsequent generations of filmmakers around the world. Moreover, it paved the way for later movements in Poland, such as the Cinema of Moral Anxiety, which continued to explore complex social and political themes with a critical and introspective approach.

Refer to the Listed Films for the recommended works associated with the movement. Also, check out the rest of the Film Movements on our website.

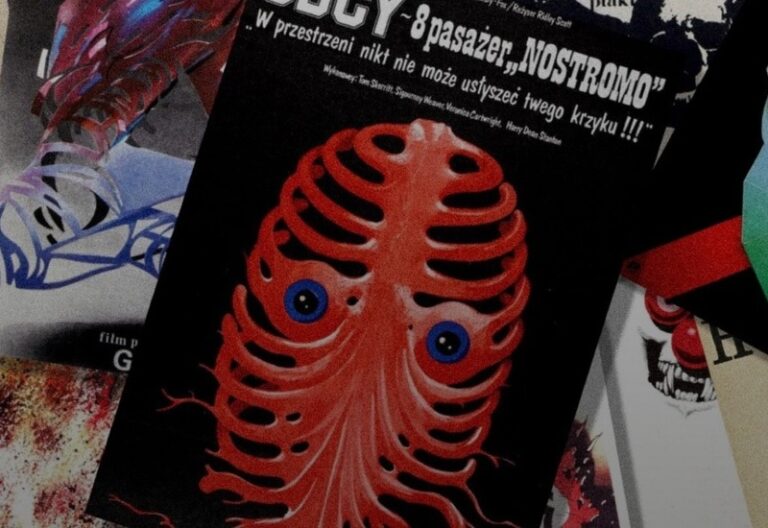

The Polish School of Posters stands as one of the most distinctive movements in the history of graphic design. Emerging in the aftermath of World War II, it transformed…

The Cinema of Moral Anxiety, or Kino Moralnego Niepokoju in Polish, represents a pivotal movement in Polish cinema, developing during the 1970s and continuing into the early…

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy was a country in ruins, both physically and economically. Amidst the rubble and despair, a group of visionary filmmakers arose to…

In the mid-20th century, a cinematic revolution was brewing in Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak New Wave, film movement characterized by visual experimentation…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…

The 1960s was a tumultuous era of change and transformation across the globe, while in the former Yugoslavia, a unique and provocative film movement known as the…