french new wave

est. 1955 – late 1960s

The French New Wave or La Nouvelle Vague, is one of the most iconic and influential film movements in the history of cinema. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing throughout the 1960s, it transformed the cinema not only in France but also worldwide, which marked cultural and intellectual transformation of the film as a medium.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Movements

Beginnings of the

French New Wave

The origins of the French New Wave can be traced to the post-World War II period in France, when the country was undergoing a major cultural and social transformation. After years of Nazi occupation, French cinema had stagnated, relying on formulaic, studio-driven productions.

However, with the liberation of France, a new generation of young cinephiles emerged, many of whom were critics for the influential film journal Cahiers du Cinéma. These aspiring filmmakers, including Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol, were passionate about cinema and critical of the conventional French filmmaking practices of the time, which they saw as uninspired and detached from real life. This dissatisfaction laid the foundation of the French New Wave movement.

In the 1950s, French New Wave pioneers found inspiration in the films of Italian Neorealism, American cinema, and the writings of film theorists such as Andre Bazin, who championed the idea of “auteur theory.” This theory proposed that directors should have creative control over their films and that their personal vision should be clearly reflected in the final work. Motivated by Bazin’s ideas and a desire to break from the traditional filmmaking, these young directors began experimenting with new techniques and narratives. They wanted to create films that reflected the changing realities of post-war France, stories that were personal and in touch with contemporary life.

The French New Wave was also fueled by important technological and economic changes. Advances in lightweight camera equipment, portable sound recorders, and faster film stock allowed filmmakers to shoot on location and with smaller crews, giving them more creative freedom and flexibility. Further, the rise of government funding and support for the arts in France, including the establishment of the Centre National de la Cinematographie (CNC), made it easier for these young filmmakers to access resources. By the late 1950s, with the release of Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows” and Godard’s “Breathless,“ the French New Wave had officially started.

French New Wave Characteristics

The New Wave filmmakers rebelled against the conventions of traditional cinema, which relied on elaborate sets and studio shooting, instead embracing location shooting and using Parisian streets, cafes, and everyday spaces as their backdrops. In their pursuit of realism, they often cast non-professional actors alongside established stars, further enhancing the naturalism and spontaneity of their work. This approach stood in stark contrast to the highly polished, meticulously controlled productions of the previous era.

In addition to their dedication to realism, films were characterized by their experimentation with narrative structures. Instead of adhering to the conventional beginning-middle-end format, many filmmakers rejected linear storytelling in favor of non-linear, fragmented, or episodic narratives.

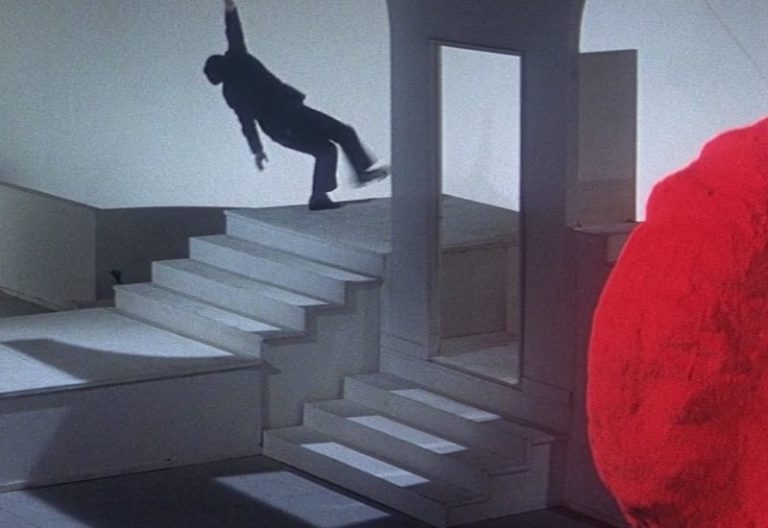

The movement introduced innovative cinematography techniques, including hand-held cameras, jump cuts, and unconventional framing. This gave their films an energetic, almost rebellious quality, evoking a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. Many French New Wave films also delved into existential and philosophical themes, with characters grappling with issues of identity, love, alienation, and the complexities of human existence.

Famous French New Wave Films

François Truffaut’s debut film, “The 400 Blows” (1959), stands as one of the defining works of the French New Wave and is widely regarded as a cornerstone of the movement. A deeply personal, semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story, the film follows young Antoine Doinel as he navigates the hardships of adolescence. Truffaut captured the restless energy and rebellion of youth, resonating with a post-war generation.

Similarly, Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” (1960) became a symbol of New Wave innovation, known for its unconventional cinematography and radical departure from classical storytelling. The film follows a couple on the run, but its plot is secondary to Godard’s bold use of jump cuts, hand-held camera work, and fragmented narrative. Godard’s subversive approach challenged traditional filmmaking methods, emphasizing style, form, and spontaneity over polished narrative coherence. “Breathless“ encapsulated the rebellious spirit of the French New Wave, with Godard pushing the boundaries of what cinema could be, not only in terms of storytelling but in how films could visually represent the disjointed, uncertain experience of modern life.

Although not a member of the original Cahiers du Cinema circle, Agnes Varda played a pivotal role in the French New Wave and remains one of its most celebrated figures, particularly as a pioneering female director in a male-dominated movement. Her film “Cleo from 5 to 7” (1962) is a masterful exploration of existential themes, following a pop singer through a two-hour journey in Paris as she awaits potentially life-changing medical results. Varda’s film blends the personal and the political, using artistic innovation to examine femininity, identity, and the anxieties of mortality. With her unique perspective and sensitivity, Varda expanded the scope of the New Wave, bringing a fresh focus on female subjectivity.

Eric Rohmer, another prominent figure in the French New Wave, contributed significantly to the movement’s legacy with his philosophical and dialogue-driven films. His 1969 film “My Night at Maud’s” stands out as one of his most acclaimed works. The film, part of Rohmer’s “Six Moral Tales,” focuses on the complexities of human relationships, moral choices, and intellectual introspection. Rohmer’s minimalist style and focus on character psychology made him a distinctive voice within the Wave.

Legacy and Lasting Influence of the French New Wave

The French New Wave’s impact on cinema is immeasurable. Its influence can be seen in the works of subsequent generations of filmmakers, from American directors like Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, who have incorporated New Wave aesthetics and storytelling techniques into their films, to international auteurs like the Hong Kong New Wave’s Wong Kar-wai, whose films exhibit the same sense of romanticism and free-spirited creativity.

In addition to shaping individual directors, the French New Wave inspired new film movements around the globe. The spirit of innovation and rebellion against conventional cinema found resonance in various countries, fostering a more diverse and dynamic global film culture. This legacy underscores the French New Wave’s pivotal role in redefining what cinema could be and how it could communicate complex human experiences and societal issues.

Finally, the French New Wave represents a revolution that challenged established norms, encouraged individual artistic expression, and reshaped the language of cinema forever. Its enduring impact is a testament to the power of cinema to engage with intellectual, existential, and philosophical themes while inviting the audience to actively participate in the storytelling process. The French New Wave continues to inspire filmmakers and captivate audiences, reinvigorating cinema with each new generation of cinephiles.

Refer to the Listed Films for the recommended works associated with the movement. Also, check out the rest of the Film Movements on our website.

In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, until mid 1980s, a cinematic revolution unfolded in Hollywood that would forever change the landscape of the film industry. American New…

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy was a country in ruins, both physically and economically. Amidst the rubble and despair, a group of visionary filmmakers arose to…

The Japanese New Wave or Nuberu Bagu, as it’s known in Japan, represents a pivotal period in Japanese cinema, marked by a wave of artistic experimentation and…

Jacques Demy appeared at the height of the French New Wave alongside contemporaries like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. Demy’s films are celebrated for their visual…

In The Beaches of Agnès, there is a scene in which Agnès Varda looks down the lens of her camera, straight at her audience, and says: “If we opened people up…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…