direct cinema & cinema vertie

est. 1957 – 1970s

Two documentary styles, Direct and Cinema Verite, unfoldedin the late 1950s, sharing a common goal of capturing reality in its most unfiltered form. Direct Cinema, pioneered in the United States, used lightweight equipment to observe events spontaneously, offering an untouched and authentic experience. Cinema Verite, originating in France, embraces a more subjective and participatory approach, acknowledging the filmmaker’s presence and allowing for interpretations.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Movements

Origins of Direct and Cinema Verite

The beginnings of Direct Cinema and Cinema Verite can be traced to different cultural, technological, and philosophical factors that characterized the 1950s and 1960s in both the United States and France. As traditional documentary filmmaking methods began to feel restrictive and detached from the evolving spirit of the decades, a desire for more immediate and authentic representations of reality fueled the emergence of these documentary movements. The social upheaval and cultural shifts of the post-war era demanded new forms of expression that could more accurately reflect the complexities of contemporary life.

In the United States, the advent of lighter, more portable cameras and sound equipment revolutionized the documentary filmmaking process. This technological innovation allowed filmmakers to capture events as they unfolded, without the need for staged scenes or intrusive setups. The influence of television journalism, which prioritized real-time coverage and on-the-spot reporting, also played a significant role in shaping Direct Cinema.

In France, the intellectual climate of the 1960s was ripe for experimentation and innovation in the arts. Influenced by existentialist philosophy and the works of avant-garde filmmakers, especially from the French New Wave, French documentarians began to challenge traditional notions of objectivity and detachment in documentary filmmaking. Cinema Verite emerged as a movement that embraced the subjectivity of the filmmaker, recognizing that the presence of the camera inevitably influenced the events being filmed.

What is Direct Cinema?

Associated with American filmmakers in the late 1950s and 1960s, Direct Cinema was a response to the limitations of traditional documentary filmmaking. It aimed to provide an untouched depiction of reality, employing lightweight, portable equipment that allowed filmmakers to be more agile and less obtrusive. The key doctrine was the minimal use of directorial intervention, aiming to present events as they naturally occurred.

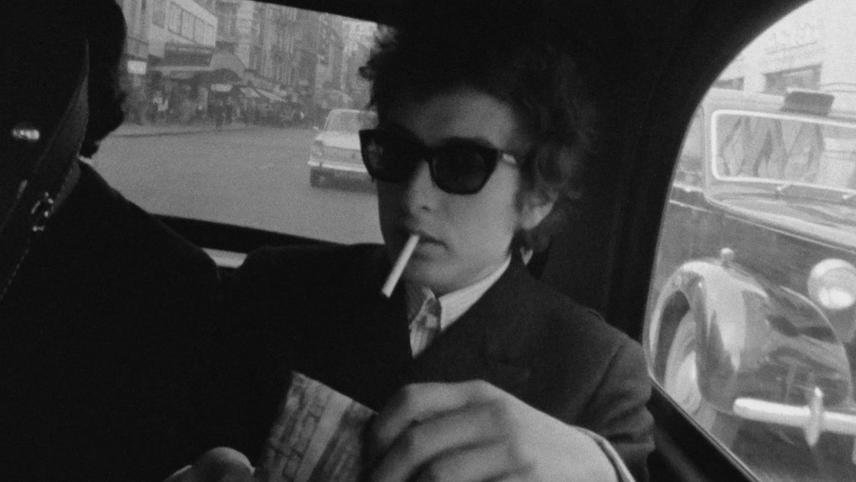

Prominent figures include Albert and David Maysles with their work “Salesman” (1968), which documents the lives of door-to-door Bible salesmen. Also, D.A. Pennebaker, with the now popular documentary film, “Don’t Look Back” (1967), which follows Bob Dylan on his 1965 tour of the United Kingdom.

The filmmakers often used observational techniques, avoiding interviews, voiceovers, and scripted scenes. The resulting films had a raw and objective quality, providing viewers with an unfiltered window into the worlds they depicted. However, this approach also faced criticism for its potential to intrude upon the privacy of subjects and for the ethical considerations associated with documenting real-life events and people participating.

What is Cinema Verite?

Cinema Verite, meaning “truthful cinema” in French, shares similarities with Direct Cinema but has its roots in the French documentary tradition. Unlike Direct Cinema, Cinema Verite allowed for a more subjective and introspective approach, acknowledging the presence of the filmmaker as both observer and participant, and the impact of the camera on the events being documented. This approach allowed for a deeper exploration of subjects, leading to a more intimate exploration of their lives.

Considered one of the founders of Cinema Verite, Jean Rouch, in his work “Chronicle of a Summer” (1961), engaged with ordinary people on the streets of Paris, asking them existential questions about their lives. The film captured spontaneous moments, reflecting on the ethical and philosophical implications of documentary filmmaking. Chris Marker, a visionary film essayist, created the documentary “The Lovely Month of May” (1963), a snapshot of post-Algerian War Paris. Known for his innovative narrative techniques, Marker captured the city’s pulse through candid interviews, street scenes, and poetic narration, creating a timeless exploration of societal shifts and individual perspectives.

Legacy and influence of Direct and

Cinema Verite

The Direct and Cinema Verite movements never came to an abrupt end, rather, they evolved. Today, their impact is evident in the diversity of documentary filmmaking styles. Filmmakers draw inspiration from these movements while embracing a wide range of approaches, including investigative journalism and essay filmmaking.

The emphasis on authenticity, a shared commitment of both movements, remains a guiding principle in contemporary documentary storytelling. The technological innovations introduced by Direct Cinema and Cinema Verite have contributed to the democratization of filmmaking, while the advent of more affordable digital cameras democratized the filmmaking process, enabling a wider range of voices to continue expanding documentary landscape.

Refer to the Listed Films for the recommended works associated with the movement. Also, check out the rest of the Film Movements on our website.

The French New Wave, or La Nouvelle Vague, is one of the most iconic and influential film movements in the history of cinema. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing…

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy was a country in ruins, both physically and economically. Amidst the rubble and despair, a group of visionary filmmakers arose to…

In the mid-1990s, a group of Danish filmmakers, led by the visionary minds of Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, embarked on a cinematic journey that would…

Postmodernist film emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, rooted in the broader cultural and philosophical movement of postmodernism. It started as a reaction…

Experimental film, referred to as avantgarde cinema, is a genre that defies traditional storytelling and filmmaking techniques. It explores the boundaries of the medium…

Independent film, often called indie film, is produced outside the major studio system. Its roots can be traced back to the early 20th century, when filmmakers began seeking…