cuban revolutionary cinema

est. early 1960s – late 1970s

Cuban Revolutionary Cinema started in the wake of the Cuban Revolution of 1959, a period that saw the overthrow of the Batista regime and the rise of Fidel Castro. The new government recognized cinema as a powerful tool for cultural and political expression, leading to the establishment of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC) in 1959. ICAIC aimed to produce films that reflected revolutionary ideals, national identity, while addressing social issues.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Movements

Origins of the Cuban Revolutionary Cinema

The roots of Cuban Revolutionary Cinema can be traced back to the revolutionary spirit that swept through Cuba during the late 1950s. The Castro-led government saw the potential of cinema to educate and mobilize the masses, promoting the ideals of socialism and anti-imperialism. The creation of ICAIC provided filmmakers with state support and resources, fostering an environment where artistic freedom and political commitment could coexist. This period was marked by a departure from commercial cinema, focusing instead on the realities of Cuban life and the aspirations of the revolution.

The establishment of ICAIC was a pivotal moment, as it marked the first time in Cuban history that cinema was institutionalized and given a central role in the cultural policies of the state. This institution aimed to create a new kind of cinema that was not only entertaining but also politically and socially engaged. The early years of ICAIC saw the production of newsreels, documentaries, and feature films that highlighted the achievements of the revolution and addressed issues such as literacy, agrarian reform, and the struggle against imperialism.

Characteristics of the Revolutionary Cinema

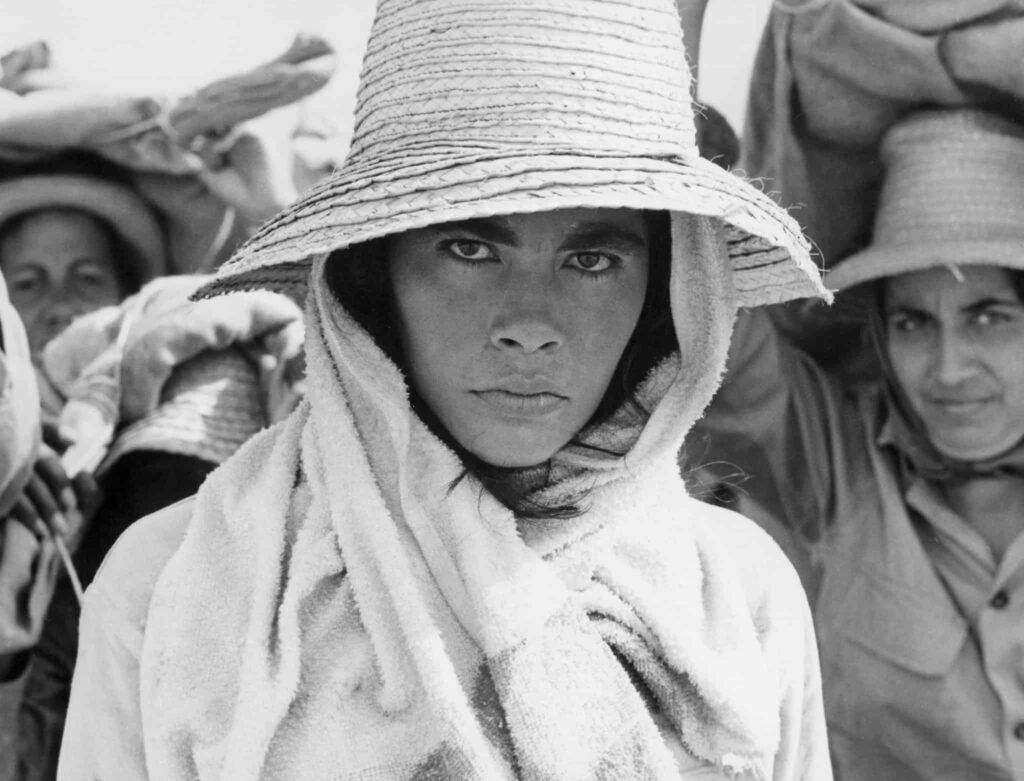

Cuban Revolutionary Cinema is characterized by its emphasis on social realism and its commitment to portraying the struggles and triumphs of the Cuban people. Filmmakers employed a documentary-style approach, often using non-professional actors and shooting on location. Themes such as class struggle, imperialism, and solidarity were central. Additionally, the movement embraced experimental techniques, drawing inspiration from Soviet Montage and Italian Neorealism.

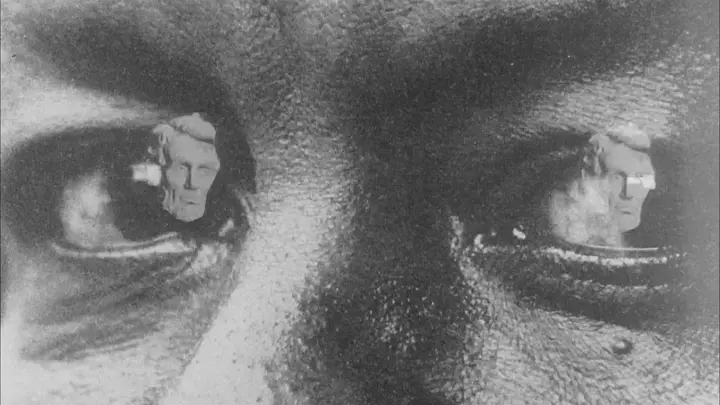

One of the hallmarks was its use of innovative narrative structures and visual styles. Filmmakers experimented with storytelling methods, opting for fragmented narratives, nonlinear timelines, and a mix of fiction and documentary footage. This approach was intended to engage viewers more critically and reflect the complexity of the social and political changes taking place in Cuba. Cinematography was another key aspect, with filmmakers employing dynamic camera movements, close-ups, and innovative lighting techniques.

Music and sound played a crucial role in these films, used to underscore the emotional tone and enhance the storytelling. Traditional Cuban music, as well as revolutionary songs, were commonly featured. The movement also placed a strong emphasis on collective filmmaking, where collaboration among directors, writers, and other crew members was encouraged to produce works that resonated with the revolutionary ethos.

Important Filmmakers and Films

Several key directors and films define Cuban Revolutionary Cinema. Tomas Gutierrez Alea, as one of the most prominent figures, is known for his critical yet nuanced portrayal of Cuban society. His film “Memories of Underdevelopment” (1968) explores the disillusionment and identity crisis of a bourgeois intellectual in post-revolutionary Cuba, blending narrative and documentary elements. This film is considered a masterpiece of Latin American cinema and exemplifies the movement’s capacity to address complex personal and societal issues.

Another significant director, Humberto Solas, gained recognition for “Lucia” (1968), a film that tells the story of three women named Lucia, set in different historical periods, highlighting the continuity of struggle and change in Cuban history.

Sara Gomez was a pioneering filmmaker whose work focused on issues of race, gender, and class in revolutionary Cuba. Her film “One Way or Another” (1974) is a seminal work that explores the lives of ordinary Cubans, particularly Afro-Cubans, and their experiences in the post-revolutionary society. The film blends documentary and fictional elements to address social and cultural transformations, making a significant impact on Cuban and international cinema.

Legacy and influence of the Cuban Revolutionary Cinema

Cuban Revolutionary Cinema played a crucial role in the development of a distinct Latin American cinematic voice. The movement’s emphasis on social and political issues resonated with filmmakers across the continent, contributing to the emergence of the Third Cinema movement.

This broader movement shared many of the goals and stylistic approaches of Cuban Revolutionary Cinema, advocating for a cinema that reflects the realities and aspirations of Latin American peoples, while challenging the dominant narratives of Hollywood & European cinema, and promoting a more authentic, politically engaged form of filmmaking.

It continues to be celebrated for its artistic innovation, political commitment, and its role in shaping the cultural identity of modern Cuba.

Refer to the Listed Films for the recommended works associated with the movement. Also, check out the rest of the Film Movements on our website.

Third Cinema is a revolutionary film movement that emerged in the 1960s as a response to the dominant ideals of Hollywood (1st Cinema) and European art cinema (2nd Cinema)…

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy was a country in ruins, both physically and economically. Amidst the rubble and despair, a group of visionary filmmakers arose to…

Cinema Novo, meaning “New Cinema” in Portuguese, was a revolutionary film movement that originated in Brazil during the 1950s. It aimed to break free from the confines…

In the early 20th century, a cinematic revolution was brewing in the Soviet Union. A group of visionary filmmakers, collectively known as the Soviet Montage School, gathered to redefine…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…

Juxtaposition is a powerful storytelling technique where two or more contrasting elements are placed side by side to highlight their differences or to create a new, often more…