woman in the dunes review

film by Hiroshi Teshigahara (1964)

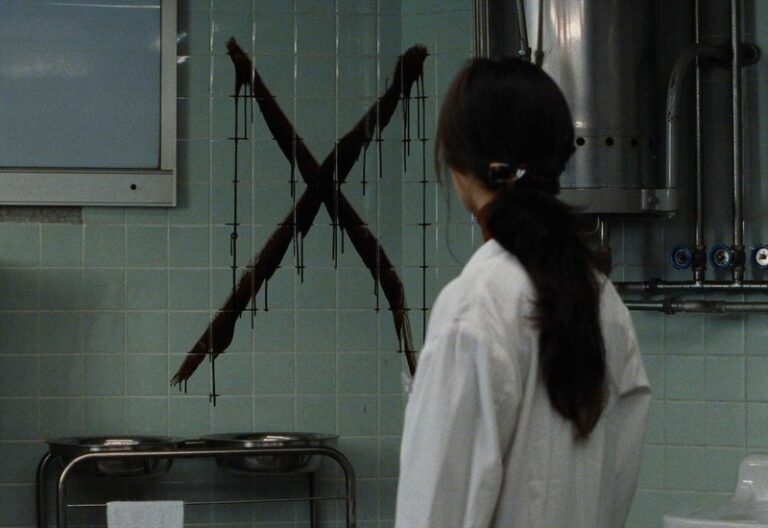

There is a casual sadism to the entomologist, both amateur and professional, which I don’t think either breed really considers. Row after row of exoskeletal corpses, pinned in mock crucifixion, taxonomized for the (enlightenment? Pleasure? Sublimated desire to “defeat” the inscrutable insectile chaos via Latin etymology?) ostensible benefit of “rational” Anthropocene.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

January 12, 2026

These macabre displays, which I have been shown on multiple occasions with the giddy half-embarrassment of a seventh grader flashing you Hustler, always induced more questions than answers, none of them comforting.

How were the victims chosen; did he draw straws? Is the crucifixion process clipped and clinical or laboriously erotic? Does the lending of Latin labels make it feel more respectable in the eyes of peers, teachers, potential crushes? Do insects feel pain? Do they posses the self-awareness to anticipate death? What, if anything, are we learning here? Who—or what—benefits from the humiliation ritual? Why does Kevin’s room smell of formaldehyde?

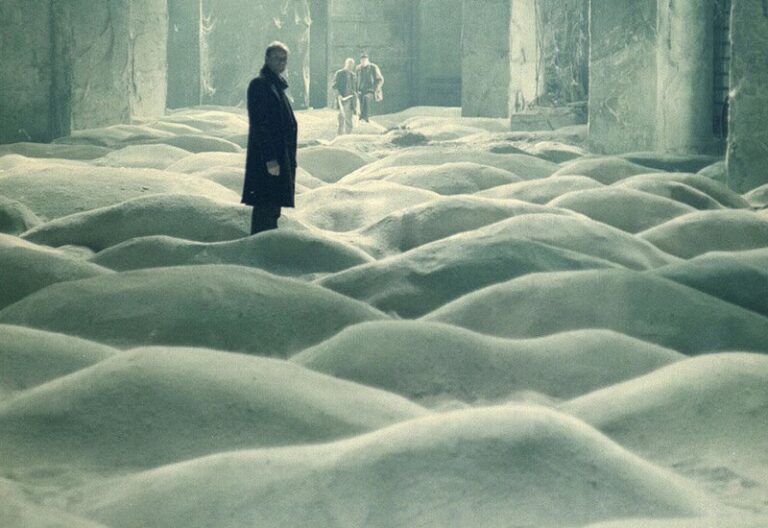

Tokyo, Kyoto, the pissant mountain-spa hamlets, they no longer exist. All is shifting grit and The Promise of the Sea. Mind you, this is only a physical transformation. All the depressing characteristics of Liberal Democratic Japan—the ennui, the anomie, the sake suicides on the installment plan, the crushing paternalist oppression of deskilled workers and women (probably some overlap there!), the pathetic vacuity of political cartoons in legacy publications, commodity fetishism to paper over the dawning realization that A Parliament With Multiple Parties Does Not A Democracy Make—are still with us, even in this “speculative” world. Eiji The Husband and Kyoko The Wife are doomed to bicker over the contours of the tomb their ruling class chose for them.

Woman in the Dunes is more or less a single tableau—a stage, if you will—for the (recursive/discursive) spiraling sociopolitical experimentation between a man who’s still delusional enough to think he can “outsmart” bourgeois superstructure and a woman who’s resigned herself to its tatami-lined cage since she was 13. This is not a scenario-relationship, which even the most starry-eyed JCP cadre would have to admit, could result in something approaching a Hegemony Shattering Epiphany or camaraderie or even a sad-cathartic “transcendence.”

Eiji The Husband and Kyoko The Wife are too set in their ways. ANPO will continue to be signed, B-12 bombers will continue to refuel in Okinawa en route to mass murder Vietnamese with Flash Gordon weaponry, commodities will be fetishized, labor will be degraded and (intentionally) blinded from an understanding of its own role in the supply chain, capitalist bureaucracy will incubate a million funny-novel mental illnesses; this is the dune from which Kyoko and Eiji must extricate themselves. I can’t say I would’ve done better.

I appreciated Hiroshi Teshigahara’s directorial chops on Face of Another, but I think the self-imposed exile to a dune-moon purgatory (a single set for 146 minutes), by forcing him to magnify the despairing sensuality of our complimentary societal agglomerations, is the better (and incredibly, a funnier!) filmmaker here. I loved how the grit clings to perspiring flesh—salt upon salt!—and the way Eiji and Kyoko’s back & forths approximate a type of anti-sitcom; punchlines without set-ups and Learning Moments where no-one actually learns.

Toru Takemitsu’s score lends sublimity as much as it mocks the tragicomedy. It sounds like 1800 birthday balloons with barbed wire for strings grating simultaneously over your deadbeat stepuncle’s wake; I never want to hear it again and I purchased it immediately with money I don’t have.

When Kyoko The Wife and Eiji The Husband fuck, those moments—as beautiful as Teshigahara films them, they’re reduced to tragicomedy as well, which is less “intentional” than congenital for the man—only reminded me of barbed wire friction, a rusty scalpel on necrotic subcutaneous pink-tar. The act of cumming, while arguably a sort of coupling-temporary transcendence, also emits exquisite glassy pain; it’s like “finishing,” but instead of a milky emission greeted by a wan smile, it’s fire ants, sawdust, malarial tumors and Tatami Mat Branding in the Key of A(tomic.)

I must credit Teshigahara for exhuming one of my more embarrassing adolescent memories: while dragooned into some friend’s pilgrimage to the (facsimile) Our Lady of Fatima shrine in Houston, I (unwisely) commented that the Portuguese apparition “looked like she was cumming, but for reasons which simultaneously repulse and thrill and forgive and doom her.” That particular family never invited me anywhere again.

Motifs of Constancy reign over Woman in the Dunes like gibbering sovereigns–granite grit, jouissance intercourse, bifurcated social reproduction, schematics for impossible wells–but only one resisted my slovenly nametag. It endures the entire runtime, a faintly perceptible but nonetheless aggravating flapflapflapthruuuuuuuuum. I knew I’d heard that sound before on a billion different occasions, usually a Thursday evening where the crowds were lonely as I. You oscillate between caffeine uprightness and supine opium daze. The film–if you wanna be thuddingly literalist about it–presents us with the culprit: a kerosene lantern. It, allegedly, produced the hypnotic flapflapflapthruuuuuuuuum. But don’t we all know better? Especially here.

It is, Dear Reader, the sound of a film projector. Admission was free; perpetuity is mandatory. Better get used to that seminal jawbreaker viscosity saturating your one good dress Polo for the remainder of your “lived, felt” existence. We all crane to the celluloid for life instruction.

Eiji The Husband’s character is sad, I’ll grant him that, his delusion is understandable—which makes it no less pathetic, but we are made to see him as the product of structural forces—but Kyoko The Wife is genuinely tragic because she is entirely clear-eyed about the forces which birthed her. She understands everything. She is resigned to the role political economy requires her to pantomime. I genuinely think it’s her self-awareness—in lieu of a self-actualization which will never come—that makes sex with Eiji so unforgivably rank. He sucks, but it’s better than no-one at all. To feel nothing or no-one down there, in there. Right?

Kyoko—in pantomiming The Cult of Domesticity, in representing 64 million other Liberal Democratic Wives—achieves a martyrdom Eiji will never be capable of: dying on your own terms. While Eiji is scheming, Kyoko is sowing. While Kyoko is producing petty commodities for a pitiless market, Eiji is grandstanding about aggrieved honor. Eiji taxonomizes, Kyoko sublimates. Eiji The Husband stomps and snorts and deflects and bargains; Kyoko mends and boils and reassures and digs and digs and digs and digs and digs because The Salt in The Grain is roughly commensurate to The Salt In Your Sweat.

Why escape to the sea when you can dig to it?

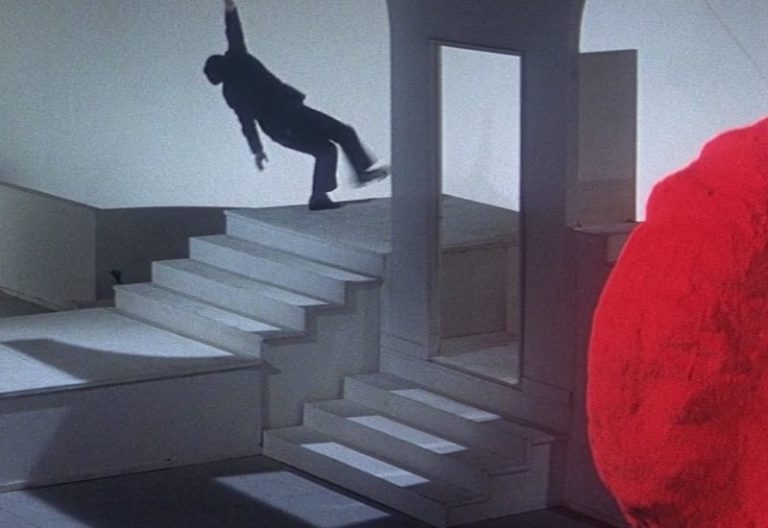

It is, I think, a curiosity (and the film’s only narrative choice which genuinely surprised me) that Eiji The Husband never successfully burrows to the Pacific from his seaweed sepulcher and ends the film on a cleansing deluge. I actively wanted (needed) the film to resolve in such a matter. It denied me that. It would’ve been so freeing, right? To see both blighted parties United In Aquatic Death?

I stewed about this and stalked back and forth between my computer and the door—roughly half the length of a kitchenette in the German Democratic Republic—and carved furrows into the carpet like a deranged foot-traffic woodpecker. Peering down, I see surly Misters and rowdy Mistresses, clad in bathrobes, shaking their fists up at me.

If Woman in the Dunes must deny me my watery absolution—and in the process, draft me into a political struggle I never knew I was delaying until I watched this—so fucking be it. Even entomologists deserve better than formaldehyde.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

A memory-wiped and defective cyborg sex slave is tossed onto the streets and taken in by a homeless woman while his corporate creators hunt him down. 964 Pinocchio was created…

The world has been ravaged by nuclear war. The planet is frozen and radiation kills anyone that ventures outside of ‘The Dome’. Soft is a shepherd for the last remnants…

The Tokyo of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Pulse” is the city at its most melancholy. Everything is enveloped in a grey fog. The sun is afraid to show its face. Brutalist architecture looms over everyone…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…

In the 90s, fear was defined by excessive gore, dark settings, and monsters in masks that chased their often-adolescent victims around their white-picket lawns. American…

The Japanese New Wave or Nuberu Bagu, as it’s known in Japan, represents a pivotal period in Japanese cinema, marked by a wave of artistic experimentation and…