family life review

film by Ken Loach (1971)

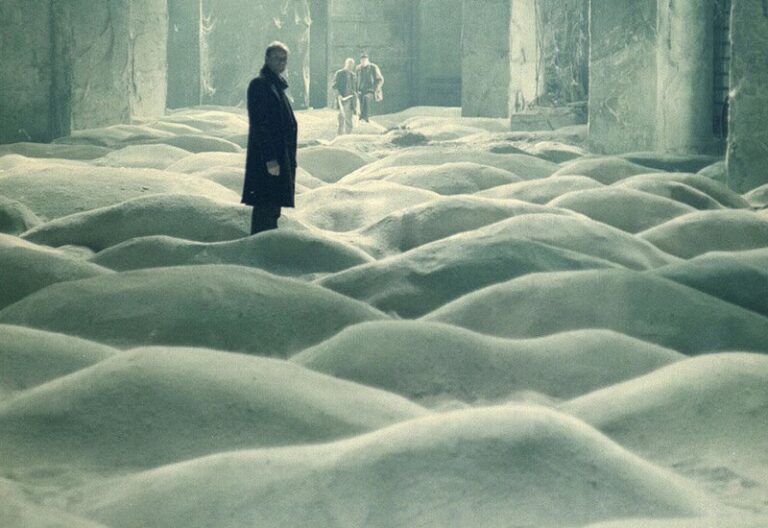

Janice (Sandy Ratcliff), a teenager living with her traditional authoritarian parents, finds her homelife tempestuously fracturing after a forced abortion leaves her with feelings of guilt and emotional neglect by her mother (Grace Cave) and father (Bill Dean). Causing a frenetic recourse and declining mental health where madness is her only refuge outside the suffocating infrastructure of those who curse a woman who has unconventional prospects outside the “normal” spheres of social acceptability. The culminating family dysfunction breaches its limits, causing her parents to turn to the public health system for a solution to Janice’s emotional instability, leading to her institutionalization.

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

December 14, 2024

Loach effectively fine-tunes the film from its broader dimensions into the more focused captive state of Janice’s reality. Bringing us within a hair’s breadth of her parents’ recoiling absolutism towards her, the narrative finds temporary balance through an unconventional therapy introduced by Dr. Donaldson, a progressive family psychiatrist. His methods seem promising for Janice but enter a stalemate with her parents, who remain steadfast in their refusal to accept any accountability for their family’s dysfunction.

Loach masterfully portrays this eternally imbalanced family dynamic, where conflict and disorder dominate, forming a precise recipe for Janice’s degradation. Dr. Donaldson confronts the parents’ denial of their daughter’s individuality, exposing their view of her as a malleable object to control and shape according to their rigid ideology of her prescribed social role. This dynamic heralds an infallible adherence to obedience and authority, shifting all blame onto Janice’s generation while perpetuating their own generation’s culture of oppression.

Blinded by emotional immaturity, Janice’s parents embody the space between ignorance and reason, revealing a parasitic multigenerational trauma. Their inability to recognize their sense of superiority as a factor in their daughter’s mental health decline highlights a deeply entrenched cultural deprivation. For them, repression is not only normalized but heralded as a virtuous ideal. By militantly enforcing these values and judging others by the same oppressive parameters, they perpetuate a divisive, corrosive ideology that undermines personal liberties and persists across generations, cementing itself as a cultural mainstay. Family Life widens its ambitions to explore these societal undercurrents while maintaining a hyper-focused and intimate lens on Janice’s experience, balancing its larger notions with an intimate and compact portrayal of her reality.

Dr. Donaldson’s efforts are no sooner thwarted by the conservative administration and bureaucratic powers that be. The psychiatric community turns over its power to more draconian methods that initially allow Janice’s now-diagnosed schizophrenia to descend further into madness. This reclaiming of power causes her to fall under barbaric treatment due to a gross misunderstanding of mental health by state-run institutions and the compromised authority of her parents. Janice’s independence is constantly at odds with her sense of self as she struggles to find her place in the world and is stuck in limbo between her freedom and her submissive position towards her parents. Her internal loyalty and principles are fear of her parents’ disapproval, leaving her unable to act upon the necessity of a 3rd option, which is to escape the guilt of failing parents who deny her autonomy. Until then, her submission to their control is the only way she will find any notion of solidarity: by agreeing to their every whim, desire, and command. Outside that sphere lies only despair and conflict.

Collectively, Tony Garnett, David Mercer, and Ken Loach tap into the therapeutic orientation of psychiatrist R. D. Laing, whose innovative approach to psychology created the foundation of Family Life, imprinting upon it a melange of naturalism through a working-class lens that employs an explicitly accurate and recognizable understanding of psychology and mental health and the injustices of the bureaucratic authority of mainstream psychiatry. Rejecting the academic opinions of a past era that categorizes schizophrenia as a biologically based, genetically inherited disease, the film suggests instead that it is a direct symptom of the individual’s environment. Laing’s environmental approach to the treatment of mental illness acts as a direct critique of the unearned positions of power in academia, where influence and power create an authority that is challenged and does nothing, even in the face of evidence, to demonstrate that those who represent authority have a rudimentary understanding of what makes that knowledge effective.

Family Life is a provocative film that levies its foresight against our contemporary and historical failures by making examples of those hypnotized into subordination by cosmetic systems of caste, the fear of social disapproval, and the obsessive need for order. While it understands the tragedy of order superseding truth both domestically and academically, those most vulnerable continually pay for society’s dissolutions—adding another tragic example of those who are failed by the system. Forming an acute lens into the Western mental health care system historically characterized by coercion and confinement.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

Joseph Losey’s 1963 film, The Servant, is loosely based on Robin Maugham’s novella. It was adapted for the screen by Harold Pinter (known for The Pumpkin Eater and…

Following the everyday lives of a group of young theater performers from rural Fenyang, spanning the late 70s to the early 90s in the aftermath of China’s Cultural Revolution…

When a car bomb explodes on the American side of the U.S./Mexico border, Mexican drug enforcement agent Miguel Vargas begins his investigation, along with American police…

Also known as the Kitchen Sink movement, was a transformative era in British cinema that emerged in the late 1950s and continued till the late 1960s. It was a period…

The Cinema of Moral Anxiety, or Kino Moralnego Niepokoju in Polish, represents a pivotal movement in Polish cinema, developing during the 1970s and continuing into the early…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its contemporaries…