what is the meaning of kino-eye?

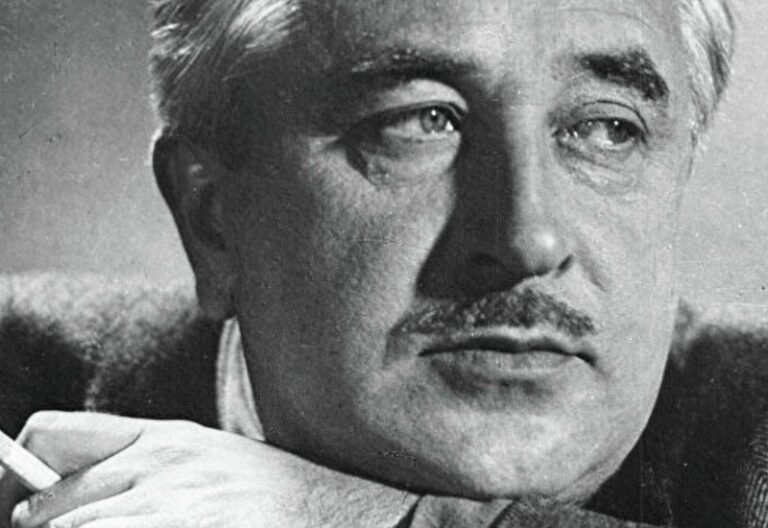

Kino-Eye (Cine-Eye) was a pioneering film technique founded by Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov in the early 1920s. It emerged as part of a larger avant-garde movement in post-revolutionary Soviet Russia, aiming to redefine the role of cinema in society. Unlike traditional narrative filmmaking, Kino-Eye focused on capturing real life, free from the artificial constraints of scripted storytelling and dramatic performances. It was not merely a style but a philosophy, driven by Vertov’s belief that the camera could reveal a deeper truth about the world than the human eye could perceive.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

Origins and Philosophy

behind Kino-Eye

Kino-Eye emerged in the context of the Soviet Union’s artistic experimentation following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. During this time, filmmakers aimed to create a new cinematic language that aligned with the ideals of socialism and revolution. Dziga Vertov became a leading figure in this movement, later named Soviet Montage.

Vertov rejected traditional narrative cinema, which he dismissed as “bourgeois theater” or “cine-drama,” seeing it as escapist and propagating illusion rather than truth. Instead, Kino-Eye proposed that the camera function as an objective observer, documenting reality as it unfolded. Vertov believed the camera had the ability to “see” the world more truthfully than human eyes, as it could capture perspectives, angles, and movements impossible for the human gaze.

The Kino-Eye approach embraced the use of montage to construct meaning through the juxtaposition of real-life footage. For Vertov, the editing process was the key to shaping the raw material of reality into a cohesive, politically charged narrative that would educate and inspire the masses. Kino-Eye was thus as much about filmmaking techniques as it was about using cinema as a tool for social transformation.

Development of the Kino-Eye Technique

The Kino-Eye movement took shape through Vertov’s experimental filmmaking collective, known as the Kinoks (short for “cinema-eyes”). The collective sought to capture everyday life in the Soviet Union and present it in a way that emphasized the dynamism and potential of the socialist state.

One of Vertov’s earliest Kino-Eye films, “Kino-Eye” (1924), epitomizes the movement’s principles. The film documents the daily lives of ordinary Soviet citizens and uses innovative editing techniques to construct a narrative of collective progress and industrialization. Vertov’s use of slow motion, split screens, and unusual angles demonstrated the camera’s potential to “see” beyond the surface of reality.

Vertov’s most famous work, “Man with a Movie Camera” (1929), is often regarded as the pinnacle of the Kino-Eye philosophy. This groundbreaking film is a meta-documentary that captures a day in the life of a Soviet city while showcasing the filmmaking process itself. The film is renowned for its inventive editing and experimental techniques, including double exposure, jump cuts, and extreme close-ups. “Man with a Movie Camera” exemplifies Vertov’s belief in cinema as a revolutionary medium capable of inspiring collective consciousness.

Other notable works include “A Sixth Part of the World” (1926) and “The Eleventh Year” (1928), which focus on themes of Soviet industrialization and collectivism, blending documentary realism with avant-garde aesthetics.

Key Features of the Kino-Eye Technique

Emphasis on Reality: Kino-Eye aimed to document authentic, unscripted moments of life, avoiding actors, sets, or traditional storytelling methods. Vertov wanted to capture the raw essence of everyday life, believing that truth could be found in the ordinary rather than the staged.

Dynamic Camera Work: Frequent usage of unconventional angles, rapid movements, close-ups, and tracking shots to create a more dynamic visual experience. These techniques allowed the camera to explore perspectives inaccessible to the human eye.

Montage: The editing process was central to Kino-Eye. By juxtaposing disparate images, Vertov revealed the hidden connections and rhythms within reality, creating meaning through visual association. This method turned everyday occurrences into poetic and visual stunning narratives.

Breaking the Fourth Wall: Kino-Eye often incorporated self-referential elements, such as showing the camera operator at work or the editing process itself, to make viewers aware of the constructed nature of cinema.

Mechanical Objectivity: Vertov believed that the camera, as a machine, could perceive and record the world more accurately than human eyes, offering an unbiased perspective. By removing human subjectivity, the camera became a tool for uncovering patterns and truths invisible to ordinary perception.

Impact and Legacy

Although Kino-Eye was initially celebrated in the Soviet Union for its innovation and alignment with socialist ideals, it eventually fell out of favor with Stalinist authorities, who demanded more straightforward propaganda films. By the mid-1930s, Vertov’s approach was largely sidelined in favor of more conventional narrative filmmaking. Despite this, Kino-Eye had a profound and lasting impact on the history of cinema.

Vertov’s work influenced the development of the documentary genre, inspiring filmmakers like Jean Rouch, Chris Marker, and Dziga Vertov’s own contemporaries, such as Sergei Eisenstein, although Eisenstein’s approach to montage differed significantly. Kino-Eye also laid the groundwork for later experimental and avant-garde movements, including the Cinema Verite and Direct Cinema movements of the 20th century. Today, films like “Man with a Movie Camera” are celebrated as masterpieces of world cinema and are studied for their groundbreaking techniques and lasting relevance.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

In the early 20th century, a cinematic revolution was brewing in the Soviet Union. A group of visionary filmmakers, collectively known as the Soviet Montage School, gathered…

The term “Cinema of Attractions” is one of the most intriguing and transformative periods in the history of film studies. Coined by film scholar Tom Gunning, this concept…

Juxtaposition is a powerful storytelling technique where two or more contrasting elements are placed side by side to highlight their differences or to create a new, often more…

The Kuleshov Effect is one of the most influential concepts in film theory, demonstrating the power of editing to create meaning and manipulate our perception. Named after…

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…

German Expressionism stands out as one of the most distinctive styles in the era of silent film. Expressionism, as an artistic movement, originally emerged in poetry and…