postmodern contemporary romance movies

Love has never been easy to define, even less so on the silver-screen. Since the beginning of cinema, the feeling has become synonymous with melodramas, period pieces, and rom coms. Surging love stories and yearning protagonists are entangled with the concept of ‘love’ as its driving narrative force.

Written by: Inés Cases-Falque | Filed Under: Film Blog

In fact, if we turn our attentions to mainstream cinema of the 80s, the Chick Flick became a particularly popular subgenre, marketed towards the modern woman who yearned for a romantic connection. Female protagonists operated as vessels for the romantic female fantasy; women were not only present on-screen, but they were allowed to desire. They were flawed, sometimes even awkward and unlikeable, but it was always in the name of love.

Films such as Sixteen Candles (1984) and The Breakfast Club (1985) focused on the adolescent experience, whereas films centred on young-adult stories such as Dirty Dancing (1987) and Moonstruck (1987) introduced mature themes such as social class and cultural disparity.

Ultimately, all these stories usually end in true romantic fashion, where the two yearning protagonists confess their feelings and apparently live happily ever after in their respective cinematic bubbles.

So, why did the last twenty-or-so years bring around a more cynical attitude to love? Postmodernist perspectives within the romance genre have been brewing for decades, particularly in the independent scene, but it seemed to float up to the surface into the mainstream just as the digital age seeped in modern dating standards.

Perhaps, in this new age, there’s less fantasy to love. Conversations blossom over phones rather than in person, and there’s less mystery surrounding potential partners as people become easier to find. Humans, it seems, need to be perceived. The digital age made that desire easier to acquire, and thus, even more sought after.

Defining ‘postmodernist’ attitudes in cinema can be challenging, and the technical aspects are still in progression. For one, they often play as a parody of themselves. There is a level of self-awareness in these films that purposely takes their audience out of the film and allows them to analyse their own past and relationships. Filmmakers want their viewers to look inward; their point in creating human connections on-screen is to provide relatability. Romance, in this context, is less a fantasy to get lost in, and more so a tool to stipulate introspection.

500 Days of Summer (2009)

An example of this technique is effectively used in 500 Days of Summer (2009), where elements of its structure parodies Hollywood rom coms. One example, famously known as the ‘Expectations vs. Reality’ scene, demonstrates this literally. Tom, the male protagonist, is coming to terms with his breakup with Summer, who he considered a soulmate. On the left side of the screen, labelled ‘expectations’, we see how Tom imagines his reconciliation with Summer might pan out, as she pays attention to him, and they seem to talk to only each other all evening, and wind up sharing physical intimacy again.

On the right, the ‘reality’ half paints a very different picture. In reality, Summer is polite to Tom, but her kindness is purely amical. She spends time with other people, treats him like any other friend, and Tom watches as, at the end of the night, she shows off her engagement ring to another friend.

It’s a paradoxical image, meant to speak relatability, melancholy, and a little tongue-in-cheek too. Tom is a sympathetic character, funny, and painfully human. He makes awkward jokes that don’t land, he lets his self-esteem shatter when Summer doesn’t return his affections, and he fails to understand her perspective on their relationship until the end. Unlike its predecessors, the characters in love no longer provide the comedy, but rather the concept of love itself becomes the farce.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

This leads us to the use of cynicism, our second characteristic of postmodernist romance. Cynical attitudes to love often results in fragmented storytelling, as the filmmakers represent on the ambiguity between characters, rather than the knowledge that two protagonists are destined to be together. Human connection is complex, and characters who seem to despise each other due to their pasts may equally still love each other deeply.

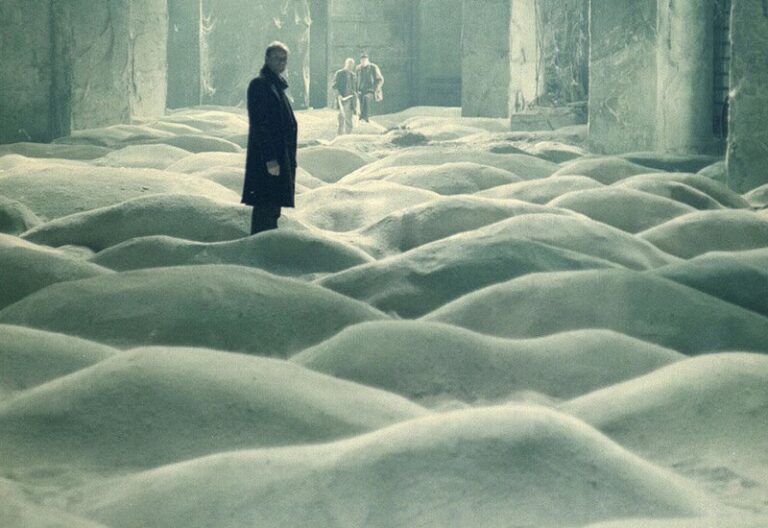

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) embodies this philosophy. The film takes place in the aftermath of Joel and Clementine’s relationship, when Joel finds out that she has cured her heartbreak by undergoing a fictional memory procedure that erases her past with Joel. Hurt at this decision, Joel decides to go through with the same procedure, only to discover how much he still cares about Clementine and their shared memories.

Eternal Sunshine is a disjointed story, told in flashbacks as Joel revisits his memories of Clementine. He confronts the ultimate paradox many of us do at the end of relationships: pleasant memories, despite their ongoing pleasantness, are now tainted since the person in them is no longer present or the same. In fact, it’s their very pleasantness that causes pain.

Joel functions as a representation of how a person can become entirely disillusioned with love as a concept. The surrealist qualities of the film, such as non-linear narrative, vibrant colour palette, and experimental sound design, only help to bring us to its conclusion: despite the pain, the memories are important. However bittersweet love may appear, it’s worth falling in love and feeling its pain all over again. There is no defining pleasure without the knowledge of pain.

Before Trilogy (1995-2013)

Postmodern love films make use of their surroundings, to the point where the cities in which these films are set become essential to the relationship. Richard Linklater’s Before Trilogy (1995-2013) famously makes use of its setting as not only a setting, but also a narrative element.

Before Sunrise (1995) takes place in the Austrian capital of Vienna, where Jesse and Céline meet on a train. Céline is bound to return home to Paris, and Jesse is set to leave the next morning to return to the States. They form a connection and decide to get off the train and spend the night together in Vienna, where they fall in love. ‘Love’ here, is defined by Jesse and Céline’s individual perspectives, as they voice their thoughts and exchange dialogue on a variety of existential topics, such as purpose, death, emotions, and their very existence.

It’s worth noting how this dialogue is structured, as if the camera were an invisible lens following a pair of lovers, intruding on the first buds of their relationship. This wildly postmodern, favouring their feelings as individuals over the objective truth.

Furthermore, Linklater strips away any grand overarching narrative of love in their story. Whilst Jesse and Céline share intimate moments, both physical and emotional, there is no grand sweeping score or melodramatic gestures between the two. When they part at the same train station early the next morning, they are tearful and hold onto each other for as long as they can. But, ultimately, they still part. There is no fantasy here. The romance was inevitable to end before sunrise, and so it does.

Nine years later, Linklater presented his audience with Before Sunset (2004), filmed with Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy, who also contributed to the screenplay, as Jesse and Céline once again. As a filmmaker, Linklater continues to blur the line between fiction and reality, just on the precedent that he waited nine years to film a sequel to the first instalment in the trilogy. With time, the actors have naturally aged, and thus, so have Jesse and Céline. There is an authenticity present that simply cannot be recreated with makeup or visual effects, because there is no need to recreate. Hawke and Delpy create a sense of immediacy just by being present, and by collaborating with Linklater on the screenplay, the words they act out are also their own.

As they reference their past meeting in Vienna, they are referencing Before Sunrise as a fictional memory and a real-life film itself, and this is where the metafiction within the trilogy is revealed. Linklater has created a sense of postmodern self-awareness unique to art itself by referencing his own within his work.

Nostalgia is key to postmodern love. The past will always shape the present, and it dictates how the future will play out. Before Sunset embodies this entirely, especially as it acts as a bridge between the first and third film. Perhaps, Linklater intends for it to literally be the present, whereas the others function as the past and future. Or, maybe he didn’t intend for any such temporal manipulation at all, and they are all their own present, nine years apart.

Ultimately, each film’s dedication to defining Jesse and Céline’s relationship through their connection with time, themselves, and their words, may be the best example of postmodern love I can offer. It is a love that is relatively mundane, yet relatable. Passionate, but far from grand. These characters are so real, perhaps because they are so unabashedly infused with the filmmaker’s own questions about life and love.

Cinema as a Mirror of Love

People, like love, are harder to find these days. But it’s become even harder to erase them. We linger in the street corners we’ve been photographed together, in the early-morning phone calls after the bars close, in the profiles we code with references to our past, hoping that someone might just notice they are missed in real-life.

Cinema has always, and will continue, to reflect our relationships with one another. In fact, I would argue that they might be the whole point of all this. All the films previously mentioned are different in their approaches to love, even different in terms of style and genre, but all are linked by a similar philosophy pertaining to love and relationships.

Linklater’s take on human connection on-screen sticks with me almost every day, and there is a quote from Before Sunset that perhaps best encapsulates cinema’s fascination with postmodernist romance entirely: “Memory is a wonderful thing if you don’t have to deal with the past”.

Who are we, as people, if not a mosaic of those we have loved before?

Author

Written by Inés Cases-Falque. A passionate film academic, writer, and cinephile who has contributed as a writer to blogs and film journals since her graduation. A founder, writer, and leading editor for Lancaster University’s CUT TO Film Journal, she mainly takes interest in the French New Wave, Nordic cinema, Japanese horror, and post-Franco Spanish political cinema. You can follow Inés on Instagram and Letterboxd.

Postmodernist film emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, rooted in the broader cultural and philosophical movement of postmodernism. It started as a reaction…

Or La Nouvelle Vague, is one of the most iconic and influential film movements in the history of cinema. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing throughout the 1960s…

Subjective cinema is a distinctive approach to filmmaking that brings viewers directly into a character’s mind, allowing them to experience the world through a personal…

World cinema refers to films produced outside the mainstream Hollywood system, encompassing a wide range of countries, cultures, languages, and traditions. It offers a window…

Tied to the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, feminist film theory critiques the portrayal of women in film, the male gaze, and the ways in which cinematic techniques…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…