what is japanese pink film?

Pink film, or pinku eiga, occupies a unique, but also misunderstood, place in Japanese cinema. Emerging in the early 1960s, it developed at the intersection of erotic content, independent production, and formal experimentation. While usually reduced to its sexual elements, it became an unexpected space for creative freedom, political expression, and stylistic innovation.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

Origins and Early Development

Pinku Eiga was shaped by economic pressure and shifting cultural boundaries within the Japanese film industry. As television drew audiences away from cinemas, major studios struggled to maintain attendance, while independent producers searched for alternative ways to survive. Erotic content, still tightly regulated but increasingly visible, became a means of attracting viewers outside the mainstream studio system.

The first widely recognized pink film is Flesh Market (Nikutai no Ichiba, 1962), directed by Satoru Kobayashi. Produced independently and shot on a modest budget, the film quickly attracted attention for its explicit subject matter. Just days after its initial release in Tokyo, police seized all known prints and negatives on obscenity charges. Rather than ending the film’s life, the incident amplified its notoriety. A censored version was later reissued and proved commercially successful.

This moment is often regarded as the birth of pink film. It revealed both the risks and possibilities of working at the edges of censorship, and it established a model that others soon followed.

Pink films were typically produced under severe constraints. Budgets were low, shooting schedules were short, and locations were limited. These restrictions fostered a fast-moving production culture that valued efficiency and improvisation. Within this framework, directors were expected to include erotic scenes, but were otherwise given surprising freedom, laying the groundwork for the genre’s later artistic and political ambitions.

Industry Shifts and Studio Involvement

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, pink film had become a significant part of the Japanese film economy. Major studios took notice, most famously Nikkatsu, which rebranded itself as a producer of “Roman Porno” films in 1971. While Roman Porno was technically distinct from independent pink film, the two shared audiences, themes, and personnel.

This period marked a shift in tone and ambition. Pink films became more stylized, more narratively complex, and increasingly willing to engage with social issues. Sexuality was often intertwined with themes of alienation, gender roles, power, and political unrest. The permissive structure of the genre allowed filmmakers to explore subjects that mainstream cinema avoided.

Themes and Aesthetic Traits

Pink films often display a tension between erotic display and emotional distance. Sex is rarely presented as purely pleasurable. Instead, it appears as a site of power struggle, frustration, or escape. Many films adopt a bleak or introspective tone, reflecting broader anxieties in postwar Japanese society.

Visually, pink cinema ranges widely. Some films favor stark black-and-white photography, minimal settings, and theatrical staging. Others embrace stylized lighting, surreal imagery, or documentary-like realism. What unites them is a willingness to use the body as a symbolic rather than merely provocative element.

A Space for Artistic Freedom

One of the most important aspects of pink film is the freedom it offered directors. Because these films operated outside prestige circuits and commercial expectations, filmmakers were often given significant creative control. As long as required erotic content was present, directors could experiment with structure, tone, and imagery.

This freedom attracted politically engaged and formally adventurous artists, especially during the turbulent years surrounding the student movements of the late 1960s. Pink films incorporated avant-garde techniques, fragmented narratives, and confrontational imagery. Some works blurred the line between erotic cinema and art film.

Pink film also developed alongside the Japanese New Wave, sharing many of its ideas while operating outside the studio system. When institutional support for experimentation began to fade in the late 1960s, pinku eiga offered an alternative space where radical ideas continued. Although not formally part of the New Wave, pink film carried its critical and rebellious spirit into more marginal and provocative territory.

Famous and Recommended

Pink Films

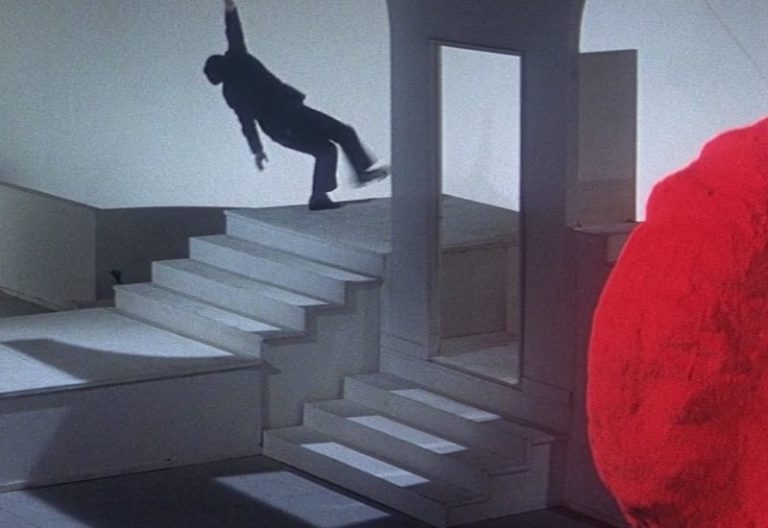

“Violated Angels” (1967, Koji Wakamatsu) – Loosely inspired by a real-life mass murder, Violated Angels is one of the most extreme and unsettling works to emerge from pink cinema. Shot in stark black and white, the film strips violence and sexuality of any erotic comfort, presenting them as acts of alienation and rupture.

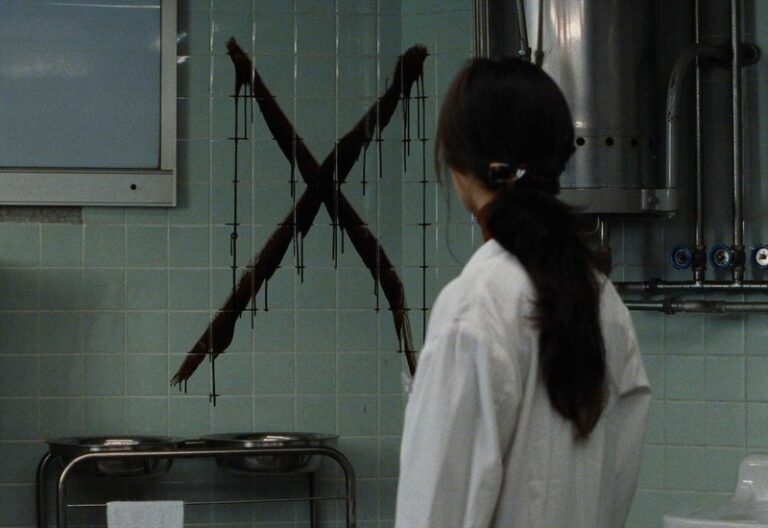

“Go, Go Second Time Virgin” (1969, Koji Wakamatsu) – Set in an urban wasteland of rooftops and abandoned spaces, the film depicts repeated cycles of violence and trauma with relentless bleakness. Sexual assault is portrayed not as spectacle but as a symptom of social collapse and emotional numbness.

“The Transgressor” (1974, Norifumi Suzuki) – It represents a more stylized and genre-inflected approach, blending eroticism with crime and psychological drama, the film explores obsession, power, and moral decay. Its polished visual style reflects the growing overlap between independent pink films and studio-backed erotic productions.

“Love Hotel” (1985, Tatsumi Kumashiro) – Directed by one of the most sensitive filmmakers to work within pink cinema, Love Hotel focuses on intimacy, guilt, and emotional isolation rather than shock. The film centers on a married man and a sex worker whose relationship unfolds within the confined space of a love hotel. Kumashiro treats sexuality with melancholy, using repetition and quiet observation to explore loneliness in modern Japan.

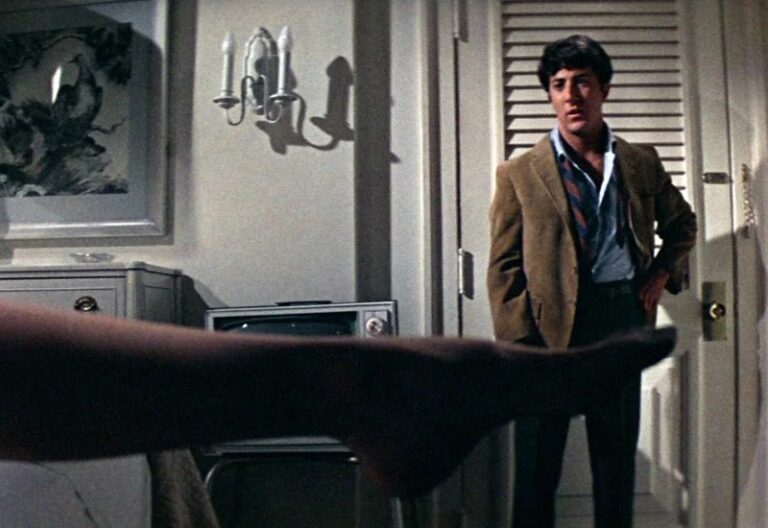

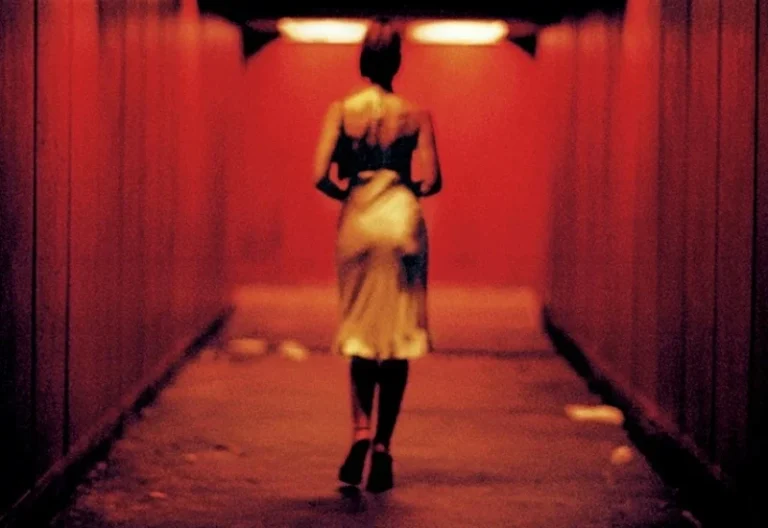

“Tokyo Decadence” (1992, Ryu Murakami) – Often described as a late echo of pink cinema, the film reflects the genre’s influence as it moved toward the margins of the 1990s film landscape. Following a high-end escort navigating sadomasochistic encounters in Tokyo, the film adopts a cold, detached tone that mirrors the emotional emptiness of its world.

Decline and

Transformation

By the late 1980s and 1990s, pink film faced declining audiences and competition from home video and explicit adult content. The theatrical infrastructure that had supported the genre weakened, and many independent theaters closed.

However, pink cinema did not disappear. It adapted. Some filmmakers transitioned into mainstream or arthouse cinema, while others continued producing pink films for smaller audiences. The genre also gained renewed attention from international critics and festivals, which began to reassess pink film as a vital chapter in Japanese film history.

Legacy and Influence

The legacy of pink film lies in its contradictions. It emerged as commercial exploitation, yet became a haven for artistic risk. It was constrained by censorship, yet found inventive ways to challenge it. It operated on the margins, yet influenced the center of Japanese cinema.

Today, pinku eiga is studied not only for its erotic content but for its role in shaping independent filmmaking, political cinema, and visual experimentation. Its history reveals how even the most unlikely genres can become vehicles for artistic expression when filmmakers are given space to work.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

The Japanese New Wave or Nuberu Bagu, as it’s known in Japan, represents a pivotal period in Japanese cinema, marked by a wave of artistic experimentation and…

Since the birth of cinema in the late 19th century, film has held an enormous cultural power. But with that power has come scrutiny — and often, suppression. The history of censorship…

In the 90s, fear was defined by excessive gore, dark settings, and monsters in masks that chased their often-adolescent victims around their white-picket lawns. American…

Cinema as an art form, has the unique ability to challenge societal norms, push the boundaries of storytelling and provoke intense emotions. One of the most striking…

The Tokyo of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Pulse” is the city at its most melancholy. Everything is enveloped in a grey fog. The sun is afraid to show its face. Brutalist architecture looms over everyone…

Giallo is a subgenre of horror-thriller films that started in Italy, characterized by its unique blend of murder mysteries, psychological horror, eroticism, and stylized violence….