brief history of sound in film

The history of sound in film is an essential chapter in the evolution of cinema, marking the transformation from silent films to the immersive, sound-driven experiences we know today. Sound in film does far more than accompanying the moving pictures, it can evoke emotions, deepen narrative layers, and completely transform the audience’s experience.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

The Silent Era:

Before Sound

Before the introduction of synchronized sound, silent films were relying heavily on visual storytelling through expressions, gestures, and intertitles. While lacking the spoken dialogue, they were rarely experienced in complete silence. Large theaters employed live orchestras, while smaller venues might use pianos or phonographs. These early musical accompaniments helped to create a mood, pace, and emotional depth, compensating for the absence of spoken words.

During this era, filmmakers developed various techniques to convey stories without sound. Title cards or intertitles, which displayed written dialogue or exposition between scenes, were a common way to ensure the audience understood key plot points. Actors commonly used exaggerated facial expressions and physical gestures as they had no words to rely on. Visual cues like lighting, makeup, and costume design also played critical roles in expressing the tone and themes of the narrative.

Though these visual tools were effective in engaging audiences, early cinema pioneers were already seeking ways to integrate sound into films. The desire for synchronized sound in films can be traced back to the late 19th century when early inventors like Thomas Edison and the Lumiere brothers began experimenting with devices that could synchronize sound and motion pictures. Edison’s Phonograph and the Lumiere brothers’ Cinématographe, while groundbreaking, could not yet fully integrate sound and image in a way that would revolutionize the industry.

The technical challenges of synchronizing sound with film were substantial. First, there was the issue of timing: sound and image had to play simultaneously, which was difficult with early mechanical devices. Secondly, amplification posed another problem. In small settings, a piano or phonograph might suffice, but for larger theaters, the ability to project sound clearly to every audience member was necessary. Early experiments with sound synchronization were usually frustrating for inventors, as phonographs and early recording devices struggled to maintain consistency with the film’s frame rate.

The First Sound Film:

The Jazz Singer (1927)

The true breakthrough came in 1927 with the release of “The Jazz Singer,” a Warner Bros. film credited as the first full-length movie to feature synchronized sound. While the majority of the film remained silent with intertitles, it included several moments of synchronized singing and spoken dialogue, creating a sensation that revolutionized the industry. Starring Al Jolson, the film marked the first time audiences experienced spoken words in sync with the actor’s lips, forever changing how we experience the cinema.

This technical achievement was made possible by the innovative Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, developed by Western Electric and used by Warner Bros. The system recorded sound separately onto phonograph discs, which were then synchronized with the film projector, offering a reliable way to sync sound and visuals that earlier attempts had failed to achieve.

“The Jazz Singer” was a commercial success, demonstrating that synchronized sound was not just a gimmick but a powerful new way to enhance storytelling. The film’s famous line, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” symbolized the dawn of the sound era in cinema. Vitaphone’s ability to provide higher-quality sound with precise coordination between the projector and the audio disc allowed audiences to experience a seamless integration of dialogue and music.

The Transition to Sound

After “The Jazz Singer,“ the race to develop more sophisticated sound technologies accelerated. Warner Bros. continued to lead the charge with their Vitaphone sound system, however, the system was soon eclipsed by the sound-on-film technologies developed by RCA and Fox, notably Fox’s Movietone and RCA’s Photophone. These systems recorded sound directly onto the film strip, eliminating the need for separate discs and ensuring better synchronization.

This transition, while revolutionary, posed significant challenges to both filmmakers and theaters. Directors accustomed to the silent era had to adapt their filmmaking techniques, as cameras and actors could no longer move as freely on set due to the limitations of early sound recording equipment, which was bulky and sensitive to extraneous noise. Theaters had to invest in new projection and sound systems, while actors had to adjust their performances for the microphone. By the early 1930s, sound had become fully integrated into the film industry, leading to the end of the silent film era and the rise of “talkies.” Hollywood studios that adapted to sound quickly, such as Warner Bros. and Fox, thrived, while those slow to adopt the technology struggled.

The Golden Age of Sound: Technological Advancements

As sound became an essential part, the demand for improved sound quality and innovation grew. The development of optical soundtracks in the 1930s and 1940s, which allowed sound to be embedded directly onto the film strip, finally started producing more consistent sound quality. Additionally, studios began experimenting with more complex soundscapes, including background noise, dialogue layering, and dynamic sound effects that gave films a more immersive atmosphere.

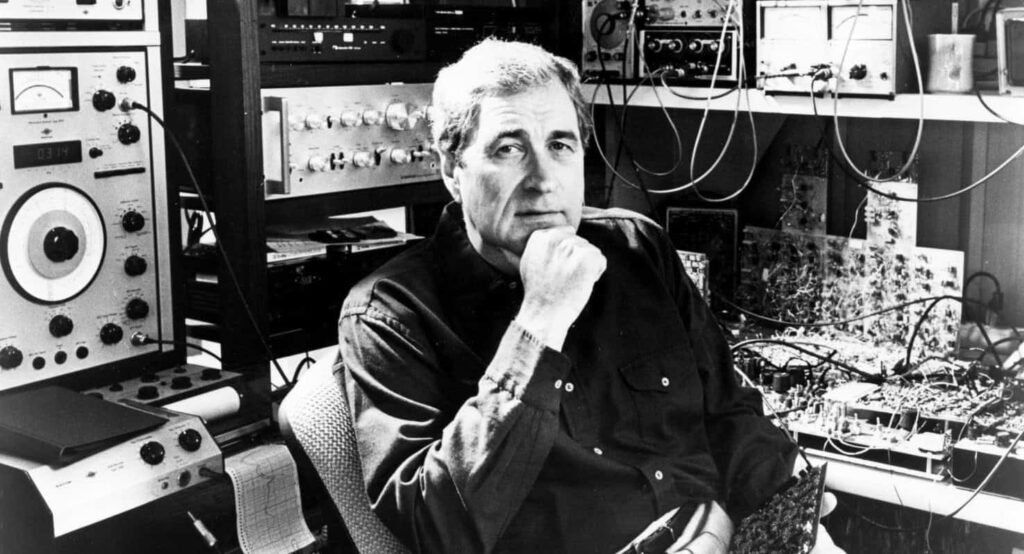

By the 1950s, stereo sound had made its debut, offering a more realistic auditory experience by dividing sound into multiple channels. The widescreen formats of the time, such as CinemaScope, further pushed the boundaries of sound design by integrating advanced audio technologies to complement the expansive visuals. One of the key figures in sound innovation during this time was Ray Dolby, who founded Dolby Laboratories in 1965.

The Rise of Dolby Sound and Modern Inovations

The introduction of Dolby sound in the 1970s marked a significant leap forward in sound technology. Dolby Stereo, first used in “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), provided cleaner, more dynamic sound, reducing noise and enhancing the overall audio experience. However, it was “Star Wars” (1977) that truly brought Dolby sound into the mainstream. George Lucas’ sci-fi epic made groundbreaking use of Dolby’s four-channel stereo sound, immersing audiences in a richly detailed sonic environment that heightened the action on screen. The film’s use of sound effects, spaceship fly-bys, laser blasts, and John Williams’ iconic score, helped redefine what was possible in sound design and set a new standard for blockbuster filmmaking.

Dolby’s innovations continued with the introduction of Dolby Surround, later, Dolby Digital, followed by THX (developed by George Lucas), and DTS (Digital Theater Systems). Dolby Digital, first introduced in 1992, expanded the possibilities of multi-channel sound with its six-channel system (often referred to as 5.1 surround sound), allowing for a more immersive experience where sound could move dynamically around the audience. This was a key innovation for action films, science fiction, and horror, where sound could greatly enhance tension, movement, and space.

The development of digital sound recording and editing in the late 20th and early 21st centuries further revolutionized sound in cinema. Films could now be mixed with greater precision, allowing for more complex layering of sound effects, dialogue, and music, while giving filmmakers additional control.

Influence of Sound on Cinema

In the early days, filmmakers faced challenges as sound equipment imposed new limitations, making fluid camera movements and long takes more difficult. This led to more static compositions in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but as technology improved, directors began to use sound with greater creativity. Sound also became crucial in creating atmosphere and emotion, especially in genres like horror, where films like “Psycho” (1960) used iconic soundscapes, such as Bernard Herrmann’s screeching violins, to heighten tension and fear.

Dialogue revolutionized character development and plot depth, allowing actors to deliver more nuanced performances compared to the exaggerated expressions of silent films. Screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s thrived on witty, rapid-fire verbal exchanges, and sound became essential for delivering humor. Furthermore, the rise of sound expanded the role of composers in filmmaking. Musical scores became integral to the narrative, as seen in films like “Gone with the Wind” (1939), “Jaws” (1975), and “The Godfather” (1972), where unforgettable music became as iconic as the visuals, forever embedded in history of cinema.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

The Cinema of Attractions refers to an early style of filmmaking, popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that prioritized spectacle and visual novelty over storytelling…

Silent films, originating in the late 19th century, represent the foundation of modern cinema. Characterized by their lack of synchronized sound, these films relied on visual…

The Golden Age of Hollywood refers to the period between the late 1920s and the early 1960s when the American film industry was at its peak in terms of creativity, influence…

The studio system was a dominant force in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was characterized by a few major studios controlling all aspects of film production…

Technicolor’s origins trace back to the 1915 when Herbert Kalmus, Daniel Frost Comstock, and W. Burton Wescott founded the Technicolor Motion Picture. The company…

Cinematography is the art and craft of capturing visual images for film or digital media. It involves the use of cameras, lighting, composition, and movement to tell…