vengeance is mine review

film by Michael Roemer (1984)

There’s a moment in the 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers where Brooke Adams does something remarkable with her eyes. They fizzle ’round her sockets like chocolate spinning fireworks. In the context of that particular film it’s an endearing idiosyncrasy, a roadside marker of individuality which we can recall In Case of Future Pod Personhood, but it confirmed something else: Adams was one of the greatest to ever do it.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

June 20, 2025

Her accolades are belated and she’s often overshadowed by (frankly, less versatile) actresses of the era like Meryl Streep, but from that evening in 2007 I was convinced, converted, an Adams Acolyte. She does wondrous things with eyes, minute twists of lips, betraying either ebullience or despair—or perhaps both at once, or neither at all.

Here—in 1984, drunk on a bootleg TWA to Providence, the city Seth MacFarlane made worthy of gentrification—she is grinning. Falteringly, perhaps, but she would tell you she’s happy. She is very insistent—to herself—that she is happy. She prides herself on Working In Television and living in an Up And Metastasizing City Like Seattle. Incredibly, she thinks Being Adopted excuses her from all that Philip Larkin Filial Haunting Coastal Shelf Shit; she is unexcused.

Vengeance Is Mine showcases a New England often neglected in the cinema of the ’80s: working-class Irish Catholic New England. Leapfrogging from Dover to Providence to Fall River to the sun-dappled Block Isle, this is the hollowed-out, deindustrialized, ascendant service economy the Lace Curtain Irish punted to their less economically successful ethnic brethren.

While we may later speculate on the exact ratio Icy-Repressive Fenian Parenting-to-Socioeconomic Exploitation plays in the mental health carnivals of Jo (Adams), Fran (Audry Matson), and Donna (Trish Van Devere), all is not despair. There is a genuine communitarian ethos to these locales. Everyone has a spare room. All parties feel comfortable swapping kids or roommates or even lovers if one household or another becomes too unbearable. It’s fascinating to see such fluidity to what are (on paper, and in the most literal sense) fairly anodyne patriarchal units.

Michael Roemer’s pen and camera—which is done a massive disservice by the epithet of “unintrusive,” it’s doing far, far more, just take note of the magisterial blocking, for one—allow glimpses at scenes we’re rarely allowed to see.

While out-and-out “joy” or “ebullience” seem to be a hopeless mirage for these characters, there is a warmth, a comfort to knowing you’ll never be homeless, never be hungry, never “turned out” of the futon carousel irrevocably. All of these people are, to varying degrees, rendered mentally unwell by some combination of economic degradation, repressive childhoods, and Faulty Wiring Upstairs.

Will they ever be happy? Most likely no, not in this lifetime. But perhaps content—if they play their bikes right and don’t shut themselves off from neighbors, and realize there is some beauty in brutal Somerville winters and the way the sun glints off the breakers on Block Isle.

But communitarian ethos, while mighty elastic, does have a snapping point: Donna, Artist in Residence on Block Isle. She has a biological daughter—Jackie, only 10 and learning rapidly about Adults and Their Morose Ways—and a spiritual daughter: Jo. As stated above, Jo was adopted (abandoned), so perhaps it’s fitting she finds Donna a vessel she can pour the accumulated frustrations and neuroses of 34 years into.

I think, by liberating Jackie from the (increasingly terrifying) tenterhooks of Donna’s imploding social reality, she can finally smile—like, for real.

Trish Van Devere’s Donna achieves what is often impossible in film: lending immense empathy to the interior reality of Those With Mental Health Struggles—not treating their autonomy as a joke, nor condescending to them—while in no way indulging behavior when it becomes dangerous, to them and those who love them.

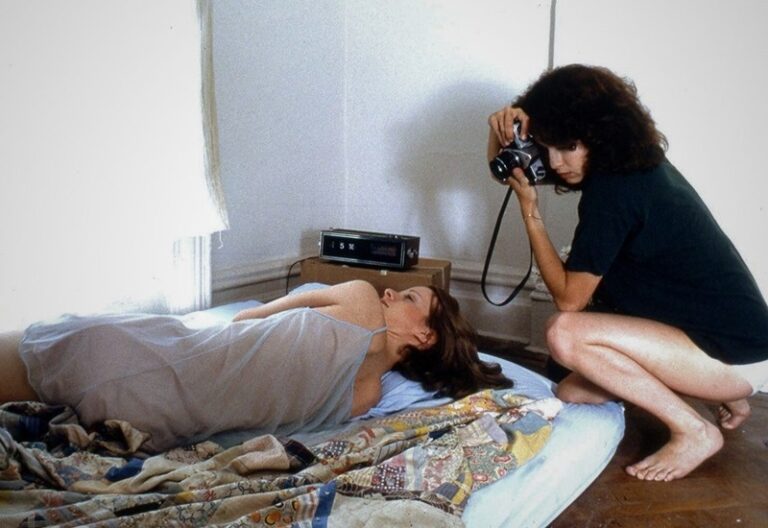

This is impossibly fucking hard, and I want to credit Van Devere and Roemer for their bravery (and research, and tenacity, and dedication to psychological liberation) in the creation of this human being. Donna is already somewhat “eccentric” by the standards of her blue-collar Fenian cohort—she crafts art of an erotic bent, she prefers the ethereal charms of Block Isle to Da Old Neighborhood—and by the time Jo Peter Pans into Providence, she’s been hospitalized on at least one occasion.

Donna is a fascinating person and her art looks incredible, but that Shameful Trifecta (economic–filial–physiological) has estranged her from husband and daughter alike. Her world is imploding, but she does her damnedest to appear serene and presentable Between Episodes. She is, in a very real way, killing herself to Appear Normal Enough To Love.

I can’t be “impartial” with Donna because there are too many shades of my mother (and to a lesser extent—or greater extent, in the reality where I never started antipsychotics—myself) coiled up within her like a rancid vine: threatening ruminations of an eschatological bent, inappropriate outbursts when Everyone Quits Paying You Attention Because They’re Conspiring Against You, a kind of saucy Machiavellianism to playing off parties you Correctly Clock As Rude (feel threatened by) in mixed company, and many, many more forensic case files too embarrassing to list here.

Perhaps that’s the watchword of Borderline Personality Disorder: it’s embarrassing. You are perfectly conscious of how ridiculous and insecure and downright annoying you’re being, and while that can lend itself to great art, it also destroys the febrile spiderwebs of Healthy Human Relationships you spent much time, and much effort, spinning.

But in a perverse way, it feels sorta good to tear them all down, stomp around on the eggs; they drove you to this point! Fuck them for their Bataan Death March through clinics, Sisyphean Burdens Borne Toward Normalcy! Why does it have to be so goddamn hard? (There isn’t a good reason. It’s just hard.)

Near the end of this woefully sad hang, Vengeance Is Mine lobs a curveball. Awaiting something devastating—though cathartic and operatic and finite; in a word, easy—Roemer denies us Clean Absolution/Defenestration and presents us with circuitous anticlimax.

Brooke Adams is back on the bootleg TWA, sober this time, allowing herself a parting glance at Block Isle & its Artist In Residence. The seafoam glare, perhaps searing and painful, is also quite pretty. Jo cannot (will never) exorcise Donna. She’ll weigh on her brain, lesions of sordid upbringing and faulty wiring forever malignant. Nothing can change that. It’s what you grew up with, and the trauma inherent there can never be bested; simply negotiated with. I’ve been trying to avoid that reckoning for most of my post-sanity life.

But something did change. Jo showed Jackie An Alternative, a productive cough. Painful? Yes. Wrenching? Doubly so. But if the offspring of Unwell Role Models/Shitty Parents/Deadening Milieu are doomed to remain haunted by forebears, transcendence never attainable, remember this: fate is not an inheritable trait.

You can learn to do wondrous things with your eyes.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

Bailey lives with her brother Hunter and her father Bug, who raises them alone in a squat in northern Kent. Bug doesn’t have much time to devote to them. Bailey looks for attention…

A photographer and her best friend are roommates. She is stuck with small-change shooting jobs and dreams of success. When her roommate decides to get married and leave, she feels…

A young woman, Janice, is living with her conservative, working-class parents, who become concerned at her rebellious behaviour, and are shocked when she becomes…

In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, until mid 1980s, a cinematic revolution unfolded in Hollywood that would forever change the landscape of the film industry. American New…

Independent film, often called indie film, is produced outside the major studio system. Its roots can be traced back to the early 20th century, when filmmakers began seeking…

American eccentric cinema is a distinctive style of filmmaking that surfaced in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, characterized by its quirky characters, whimsical…