a brief introduction to jacques demy

In the early 1960s, the French New Wave had taken over European cinema screens and disrupted the studio-driven status quo of post-World War II cinema. No longer reliant on the conventional narratives or classic literary adaptations, the New Wave filmmakers strived towards experimental, personal, and, as penned by André Bazin, auteur cinema.

Written by: Inés Cases-Falque | Filed Under: Film Blog

Jacques Demy was one such auteur, and yet, his career did not follow the same as many of his French New Wave peers. As with all film movements, the conventions of that artistic era, once exhausted, became conventional and suffocating themselves regardless of how atypical they once appeared. Demy’s approach to style and filmmaking took an interesting change, and whilst he still utilised certain aspects of New Wave principles, he also took inspiration from classic Hollywood cinema and silent films.

Early Works

(Lola & Bay of Angels)

Demy released his directorial debut, Lola (1961) at the height of the French New Wave. The film takes place in Nantes, where Demy himself grew up, and was shot entirely on-location, following a crucial convention associated with the movement at the time.

In fact, Demy’s reliance on his personal connection to Nantes is vital to the film; Lola, played by Anouk Aimee, is hoping to leave the seaside town behind and reunite with her lover, Michel, but her work as a cabaret dancer attracts many other men into her life, including an American sailor, called Frankie, and a man she used to know before the war, Roland, who is now struggling to find work.

Tinged with melancholy, as Demy infuses the film with the post-war aimlessness that plagued many young men and women at the time, he provides the existential element through the nature of human connection as Lola focuses on its characters rather than a narrative. Demy prioritises authenticity, even on a technical level, as the use of hand-held cameras and direct diegetic sound contrasted with the polished filmmaking techniques employed in Hollywood studio cinema.

Bay of Angels (1963) followed a similar style. Primarily shot on the French Riviera, between Nice and Monte Carlo, Demy turns to a more fluid approach to filming his characters, perhaps to complement the more glamorous setting.

The Umbrellas of

Cherbourg (1964)

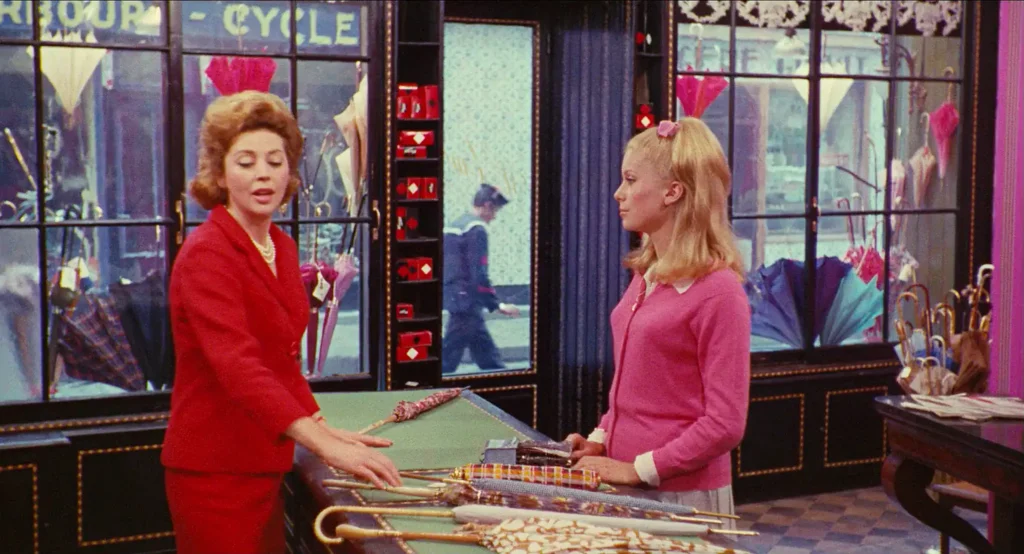

In the mid-60s, the New Wave was losing steam. The initial sparks and innovation had run their course, and a new generation of radically political filmmakers were taking centre stage. Jacques Demy’s career, however, changed trajectory entirely. In 1964, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, where Demy eventually took home the Palme d’Or and introduced the audience to a new trajectory in his career.

Gone was the black-and-white cinematography, conversational dialogue, and primarily diegetic sound; Umbrellas was a dreamlike musical, starring a then-unknown Catherine Deneuve and a music-driven film that tore him apart from his peers and the New Wave conventions. Most notably, Umbrella’s structure could be described as almost operatic.

Godard and Truffaut continued to peddle New Wave classics such as Le Mépris (1963) and The Soft Skin (1964) into the cultural sphere, and still focused on more experimental, character-driven filmmaking techniques such as prioritising natural lighting and sound, fragmented editing, and handheld cameras, Demy veered more towards the Hollywoodian technique. He crafted a set with a vibrant colour palette, to produce a more fantastical aesthetic, and chose to preserve the sound quality of the musical by prerecording the score and layering it on top during post-production.

This method of filmmaking is much more akin to the studio system, and Demy chose to prioritise the plot just as much as his characters, in an almost Shakespearean narrative of two lovers separated by their socio-economic statuses.

However, it’s worth mentioning that, whilst Demy didn’t enforce a story in Umbrellas that was as personal as Lola or Bay of Angels, he didn’t abandon the New Wave philosophy entirely. In fact, there are still many elements of social realism included in Umbrellas, such as Guy being drafted in the Algerian War in the first act of the film, a conflict which had only ended two years prior to its release.

The Young Girls

of Rochefort (1967)

His next musical, The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), proved to be another international breakthrough, and once again became famous for its bright, pastel cinematography and musical score. I would argue that Young Girls is even further entrenched in his bonbon style of filmmaking, as he places further emphasis on choreography and musical numbers, although he veers away from them seeming too over-rehearsed in favour of more freedom of movement.

The mise-en-scène is another visual treat that furthers his auteurism, as he uses colour in the costuming to emphasise tone, emotions, and character status. Complemented by 60s silhouettes to reflect the era, the twins Solange and Delphine are nearly always matching, with sometimes only slight colour or pattern differences to set them apart. Their sisterly bond is reinforced, and preferences for pieces associated with mid-60s trends such as go-go boots, wide-brimmed hats, miniskirts, A-line dresses, and bold tights. Young Girls became a fashion and aesthetic phenomenon, later influencing television shows, films, and musicals, including most famously Damien Chazelle’s La La Land (2016).

Donkey Skin (1970)

Donkey Skin was released in 1970, another Catherine Deneuve-led musical fantasy based on the fairytale by Charles Perrault and has become a French cult-classic. Though still bright and enchanting, Demy turns to a more watercolour-like palette for the film, rather than confectionary visual. This film departs from social realism entirely in favour of the uncanny. In fact, compared to his more light-hearted films such as Young Girls, Demy emphasises the dark twisted elements of the fairytale, including themes of rape, incest, and murder.

The film remains iconic for its visual elements, especially its on-location set design and costuming. Filmed in France in several castles around the country, Donkey Skin firmly plants its feet in the mystical world of Perrault’s story, and further adds to the fantasy by implementing its musical score, symbolism within colour, and weaving together elements of surrealism to highlight the artificiality of Demy’s fairytale vision.

Legacy & Influence

His career slowed considerably after the 70s, though A Room in Town (1982) perhaps saw a resurgence in his career, another musical with a similar stylistic approach as his previous efforts but with a considerably darker, political direction. However, it did not achieve anywhere near the success and cultural significance of his previous efforts, and the director passed in 1990, after a filmmaking career that spanned more than thirty decades.

Jacques Demy’s legacy is almost unmatched within the musical zeitgeist in modern-day cinema. Celebrated for his prowess with visual elements such as mise-en-scene, costuming, and cinematography, his initial endeavours in the French New Wave movement are not dampened by the success of his Hollywood-inspired musicals. His ability to marry the personal realism of the New Wave with fantasy and fairytale cemented his position as an auteur of cinema.

Author

Written by Inés Cases-Falque. A passionate film academic, writer, and cinephile who has contributed as a writer to blogs and film journals since her graduation. A founder, writer, and leading editor for Lancaster University’s CUT TO Film Journal, she mainly takes interest in the French New Wave, Nordic cinema, Japanese horror, and post-Franco Spanish political cinema. You can follow Inés on Instagram and Letterboxd.

Or La Nouvelle Vague, is one of the most iconic and influential film movements in the history of cinema. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing throughout the 1960s…

The studio system was a dominant force in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was characterized by a few major studios controlling all aspects of film production…

In The Beaches of Agnès, there is a scene in which Agnès Varda looks down the lens of her camera, straight at her audience, and says: “If we opened people up…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory suggests…

Mise en scène is a French term that means “placing on stage” and encompasses all the visual elements within a frame that contribute to the overall look and feel of a film. Originating…