stroszek review

film by Werner Herzog (1977)

The thing that struck me most about “Stroszek” was the inability of Germans to dress themselves. They pick out cowboy hats, greasy leather jackets, rhinestone vests, ferret fur coats, even clogging shoes, and then walk around outside like this is all normal.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

January 8, 2025

I believe this is one of Herzog’s signature traits; emphasizing the more bizarre side of Germanness, the Teutonic spirit run wild. Even though Herzog is preoccupied by the unbearable weight of capitalist modernity, I couldn’t help but grin at those goofy krauts and their wardrobe. No matter how bad things get, Herzog will slide in some truly bizarre humor, even if it’s more “clever” than funny. We don’t know why Bruno Stroszek (Bruno Schleinstein) was sent to prison. We can infer that it’s the result of some drunken petty crime.

We immediately feel concern for him because prison, while it is an institution designed to crush all light and spirit and hope, might have been an alright place for Bruno. He’s that warped. He cannot make it on the outside. He isn’t necessarily “mentally ill” or a “degenerate,” he simply lacks some fundamental understanding of power structures. Over of the course of the film, he will be beaten for it, sexually humiliated for it, extorted for it, and eventually forced into suicide over it.

Despite being a pariah in almost every way, Bruno has genuine friends. There’s the elderly gentleman (Clemens Scheitz) who brings bird cages, shares piano melodies, and engages in late-night conversations about anything and everything. There’s Eva (Eva Mattes), a prostitute down on her luck, who is genial and strong willed, but the wills of her oppressors are stronger.

This is not a story where the lovable loser rises above his foibles and kicks ass in the name of his friends’ honor. Bruno struggles even to defend them verbally while they’re being laughed at. For this, he gets his face screwed up, his eyes roll like errant pinballs, and his permanent facial fuzz bristles with a surprising amount of decibels. Bruno wants to react, to strike out so badly. But he can’t. It isn’t in his nature. He is capitalist modernity’s whipping boy, forever doomed to take it and take it again and take it again until he stops breathing.

I really liked Eva Mattes as, well, Eva. Perhaps the distinction between actor and character doesn’t matter too much in a film like this. Her relationship with Bruno, I suppose, could be called unconventional. It doesn’t fit into any narrow hetero-normative boxes. Bruno has the potential for possessiveness, for jealousy. Eva displays some home maker traits, like bringing him coffee while he’s playing piano. But there are plenty of other times where this isn’t the case at all. Remember when they’re haggling over the TV as equals? It’s a relationship that escapes easy definition, except that I was certain they were doomed from the start.

A lot of Europeans have a funny relationship with American culture. The French go hog wild for Bukowski, the Scandinavians even give Art Crumb’s most racist cartoons a pass. The Germans, in their irritatingly eternal placidity, really really love the stoic prairies of the Great Lakes states. Herzog makes plain his fetish for Friday Fish Fry’s, deceased squadrons of Hamm’s empties, those weird mobile home colonies surrounding a pond filled with inedible mutant trout. The man has a love affair, and it isn’t with Eva Mattes.

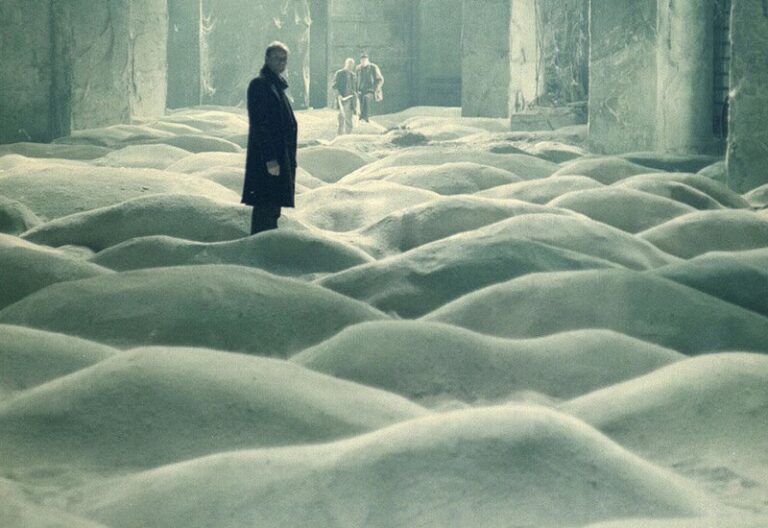

The ending is not surprising. It isn’t really supposed to be. It’s telegraphed from the first shot of a man (barely) leaving a prison. Herzog wants us to focus on his somewhat obvious point: that life is like a headless chicken staggering around in circles until we die. I don’t really agree with his thesis, but I can understand where he’s coming from. The way the animals (and he really means us) are trapped in performing an endless parade of parlor tricks for gawking spectators, is a haunting image to go out on. In some way, I feel like Herzog is piling on miserabilist imagery to be remembered, as if he isn’t confident enough in his other moments of humor and warmth and goofy hangouts.

This is a film, to quote film scholar Peter Griffin, that insists upon itself. Either you hop on Herzog’s bandwagon or show yourself the door. I was wracked with indecision because I spent the entire 107 minutes unsure if I bought into Herzog’s world or not.

I’m still not sure if I do. I found his characters to be, on one level, completely impenetrable, and on other, achingly real. I did not understand them but I did feel for them, cared about what happened to them. Herzog made me feel like an alien, not really comprehending these strange creatures but desperately wanting to figure out why they made me feel so sad. Maybe that’s an accomplishment in itself.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

A 1993 British black comedy drama film starring David Thewlis as Johnny, a loquacious intellectual, philosopher and conspiracy theorist. The film won several awards, including…

Anora, a young sex worker from Brooklyn, gets her chance at a Cinderella story when she meets and impulsively marries the son of an oligarch. Once the news reaches Russia…

Envisioned on the picturesque coast of Southern California and based on the book of the same title, the collaborative efforts to put Midnight Cowboy on screen resulted…

New German Cinema or Neuer Deutscher Film, is a film movement that started in the late 1960s, and thrived throughout the 1970s and 1980s. It represents a significant…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…