what is film editing?

Film editing, sometimes referred to as the “invisible art,” is the process of selecting, arranging, and assembling shots to create a cohesive and compelling story. It plays a pivotal role in shaping a film’s narrative, pacing, and emotional resonance. By combining visuals, sound, and timing, editors create the final version of a film that serves the director’s vision. Beyond mere technical work, editing in film is an art form that influences how a story unfolds, the rhythm of scenes, and the emotional connections we feel with the characters and events on screen.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

Early History and Development of

Film Editing

Editing in film dates back to the late 19th century, emerging alongside the birth of cinema itself. Early films, such as those created by the Lumiere Brothers and Thomas Edison, consisted of single, unbroken shots capturing events in real-time. These films, while innovative for its time, lacked any form of narrative structure. The concept of editing as a storytelling tool emerged with Edwin S. Porter’s groundbreaking work in “The Great Train Robbery” (1903). Porter introduced the idea of cutting between shots to depict simultaneous action in different locations, pioneering the use of continuity editing. This marked a shift, transforming films from static recordings into dynamic visual narratives.

Silent Film Era:

The Evolution of Storytelling

During the silent film era, editing became a powerful means of storytelling. D.W. Griffith, one of the most influential early filmmakers, demonstrated the potential of editing to shape narrative structure. His 1915 epic, “The Birth of a Nation,” popularized techniques such as parallel editing, which alternates between different story-lines occurring simultaneously, and close-ups, which brought emotional nuance to characters’ expressions.

Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein elevated editing to an art form with the development of montage theory. Eisenstein’s film “Battleship Potemkin” (1925) showcased his belief that juxtaposing unrelated images could create new meanings and evoke powerful emotions. His use of rapid cuts and dynamic composition transformed editing into a tool for intellectual and emotional engagement.

The Sound Era:

Hollywood’s Golden Age

The advent of synchronized sound in the late 1920s revolutionized film editing. With the introduction of dialogue, sound effects, and musical scores, editors had to synchronize visual and auditory elements seamlessly. The transition was challenging, as early sound technology limited the mobility of cameras and editing techniques. However, innovations like the Moviola, the first device designed for editing film, helped to streamline the process.

During Hollywood’s Golden Age (1930s–1950s), continuity editing, also known as the classical Hollywood style, became the industry standard. Editors like Margaret Booth and Anne V. Coates perfected techniques such as the invisible cut, where transitions between shots are so smooth that they go unnoticed by the audience. This approach emphasized storytelling clarity and maintained spatial and temporal continuity.

The classical Hollywood style relied heavily on techniques like match on action, eyeline matching, and the 180-degree rule to create a cohesive cinematic experience. By prioritizing seamlessness and narrative coherence, editors played a crucial role in shaping the immersive quality that defined Hollywood films of the era. All this laid the groundwork for the editing conventions still widely used in filmmaking today.

Post-War Innovations:

New Wave Movements

The post-war period saw the emergence of avant-garde and experimental approaches to editing. In the 1950s and 1960s, filmmakers associated with movements like the French New Wave challenged traditional editing conventions. Directors like Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut employed jump cuts, abrupt transitions that disrupt continuity, to draw attention to the filmmaking process itself.

Films such as Godard’s “Breathless” (1960) embraced this fragmented style, which reflected the spontaneity and subjectivity of modern life. In Italy for example, neorealist filmmakers like Vittorio De Sica used long takes and minimal cutting to emphasize authenticity and the passage of real time. These innovations expanded the language of cinema, offering alternative ways to shape narrative and meaning.

Modern Ear:

The Digital Revolution

The late 20th century brought another seismic shift with the advent of digital technology. Non-linear editing systems (NLEs) like Avid and Adobe Premiere Pro replaced traditional film splicing and tape-based systems, allowing editors to work more flexibly and efficiently. Digital tools enabled seamless integration of visual effects, color grading, and sound design, pushing the boundaries of creative possibilities. Films such as “The Matrix” (1999) demonstrated how digital editing could enhance storytelling through intricate visual effects and rapid-paced cuts. Today, editing continues to evolve with advancements in artificial intelligence and virtual reality.

Famous Film Editing Techniques

Continuity Editing: Or the classical Hollywood style, ensures smooth transitions between shots to maintain spatial and temporal coherence. Techniques like match on action and eyeline matching create an illusion of seamlessness, keeping viewers immersed in the story.

Montage: Pioneered by Soviet filmmakers, montage editing involves juxtaposing images to generate new meanings or emotional effects. This technique is used to convey the passage of time, compress complex ideas, or heighten dramatic intensity. Soviet montage theory, emphasized the power of editing to evoke intellectual and emotional responses, with iconic examples such as the “Odessa Steps” sequence in “Battleship Potemkin” (1925).

Jump Cuts: Popularized by the French New Wave, jump cuts are abrupt transitions that omit parts of a scene. They create a jarring, fragmented effect that draws attention to the constructed nature of cinema and disrupts narrative flow. This technique is often used to convey urgency or disorientation, as seen in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless” (1960), where jump cuts became a defining stylistic feature.

Cross-Cutting: Also known as parallel editing, cross-cutting alternates between two or more scenes happening simultaneously. This technique builds suspense, as seen in films like “The Godfather” (1972), where parallel editing heightens dramatic tension.

Match Cuts: A match cut transitions between two visually or conceptually similar shots, creating a sense of continuity or symbolic connection. One of the most famous examples is the bone-to-spaceship cut in Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968).

Slow Motion and Fast Motion: Manipulating the speed of footage can emphasize action or create dramatic impact. For instance, slow motion is used effectively in films like “The Matrix,” (1999) while fast motion often serves comedic or surreal purposes.

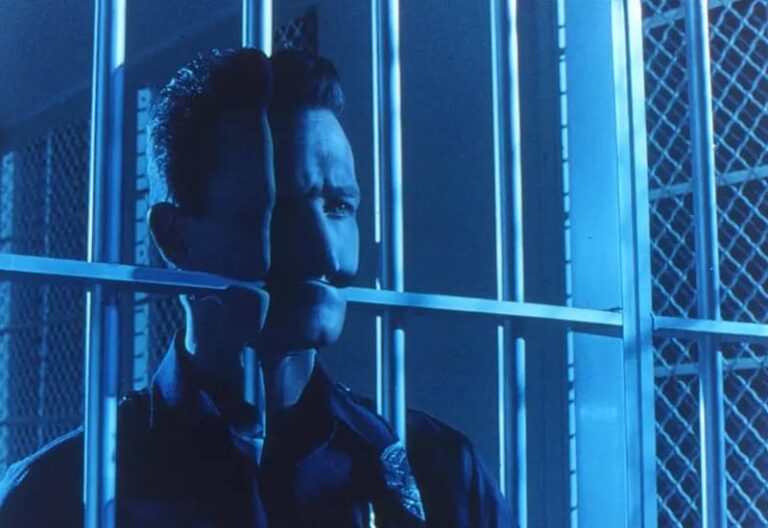

Split Screens: Split screens display multiple images simultaneously, allowing filmmakers to show parallel actions or contrasting perspectives. Brian De Palma used this technique extensively in his film “Carrie” (1976), heightening tension by juxtaposing simultaneous events in a single frame. This visual device offers a dynamic way to present complex narratives or thematic contrasts.

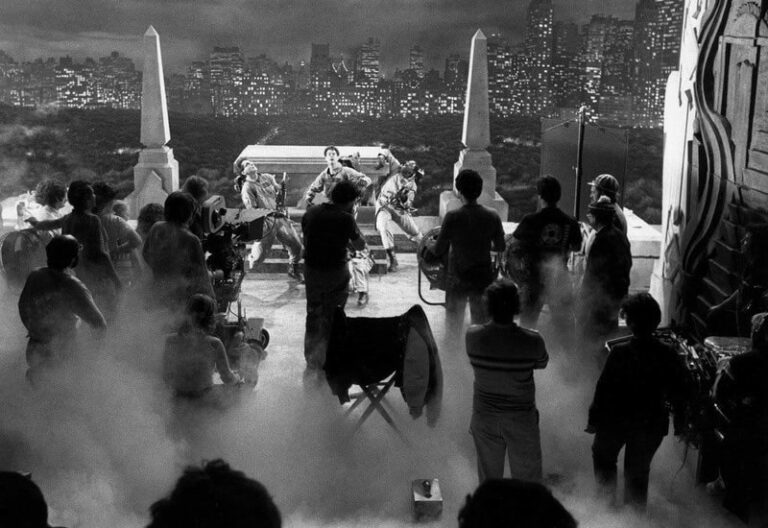

The Role of the Film Editor

Film editors are often called the “unsung heroes” of filmmaking. Their work extends beyond cutting footage; they collaborate closely with directors, cinematographers, and sound designers to shape the overall vision of a film. Editors decide on the pacing of scenes, the arrangement of shots, and the use of visual transitions, all while ensuring continuity and emotional coherence.

In modern cinema, editors also work with visual effects teams to integrate CGI seamlessly into live-action footage. Legendary editors like Walter Murch (“Apocalypse Now”) and Thelma Schoonmaker (“Raging Bull” and “Goodfellas”) have demonstrated how editing can elevate storytelling to new heights, blending technical precision with artistic sensibility.

Through their work, film editors bridge the gap between raw footage and a polished final product, transforming hours of material into a cohesive and impactful narrative. Their ability to create rhythm, build tension, and evoke emotion ensures that the audience becomes fully immersed in the story. In many ways, editors are the invisible architects of cinema.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

Special effects in film have always been a kind of magic – tricking our eyes into seeing the impossible, making the unreal seem real. It’s a craft that’s been around almost…

The studio system was a dominant force in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was characterized by a few major studios controlling all aspects of film production…

Mise en scène is a French term that means “placing on stage” and encompasses all the visual elements within a frame that contribute to the overall look and feel of a film…

Juxtaposition is a powerful storytelling technique where two or more contrasting elements are placed side by side to highlight their differences or to create a new, often more…

Technicolor’s origins trace back to the 1915 when Herbert Kalmus, Daniel Frost Comstock, and W. Burton Wescott founded the Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation. The…

Film production is the process of creating a film from its initial concept to the final product. It involves numerous stages, each requiring a collaboration of talents, skills, and resources. The…