yesterday, today and tomorrow review

film by Vittorio De Sica (1963)

Frederick Douglass had a ready-made riposte whenever people ragged on him for not being patriotic enough: “What is the Fourth of July to a slave?” The characters of this film have something similar: “What is The Italian Miracle to the itinerant street hawker or the middling call girl?” I love when entire movies are built around refutations to terrible Life Magazine spreads.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

May 18, 2025

De Sica’s Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow is a triptych, not an anthology. That’s an important difference because these are not separate stories; they are dueling social classes jostling for the sympathy of the audience. Whether you identify with the perpetually pregnant Neapolitan cigarette hustler or the industrialist’s wife suffering from molten levels of ennui is entirely up to you. However, if you feel nothing for the wondrously dysfunctional hijinks of the third segment’s Call Girl-Daddy’s Boy couple, I fear for your soul.

Act One might be the most purely De Sica. Adelina and Carmine raise a brood of rapidly multiplying children in their peeling yet beautiful tenement. Local capitalists keep trying to repossess their furniture because of some bullshit involving “paying on time.” I don’t fucking care. Anything above 10,000 lira deserves a globule of phlegm in the face. This is Sophia Loren at her most powerful. She rules this household, both as morale cheerleader and primary bread winner.

In an incredible subversion of what we might imagine as traditionally feminist angling, Adelina’s decision to pump out as many kids as possible actually increases her economic autonomy—surplus bambini are able to run numbers, hawk cigarettes, perform essential housework, and literally keep her out of jail, as the Italian state apparently cannot imprison pregnant women, while they are with child and five months after. Sometimes you gotta game the system.

I will never forget the rows of itinerant street peddlers in this film. The pigs try to lock them up, slap them with fines, but it’s like playing Casual Employment Wop A Mole. This sort of floating employment, generally known as a phenomenon of Africa or Latin America, was essential to survival in Southern Italy for decades after Mussolini got righteously aired out. I know the Milanese snobs say “Africa starts at Naples,” but did they know the Informal Economy subsidized a great deal of that much ballyhooed Italian Miracle?

Perhaps the history of unequal development has a sense of irony. In 2024, huge swaths of Americans are dependent on App-Based Employment. I have friends in Brooklyn who are forced to walk the dogs of Met Gala PR ghouls for far less money than they’re entitled to. Africa starts at Staten Island. Favelas nestling the axe-throwing bars of Park Slope.

Act Two is the least satisfying, but I still found it interesting. You have the wife of an industrialist with her own bank account and relatively dependable lover, which is hugely progressive for that social class in 1963. Obviously, her life is a comfortable nightmare. When you have no “real” problems you begin to sweat, start finding issues with the tiling, develop something called “ennui.” I still found Anna sympathetic because she knows something is wrong with the world.

She still loathes and fears poor people, but she’s gradually realizing self-actualization will never be found at Knights of Columbus benefits or within Christian Democracy pamphlets loudly proclaiming COMMUNISTS WANT TO LEGALIZE HORMONAL BIRTH CONTROL AND/OR SELL RADICAL LITERATURE TO WILDCAT STRIKERS OUTSIDE THE FIAT GATES. Yes, and they’re fucking right to!

Act Three is a warm, mealy nugget. It’s sort of like Jeanne Dielman if Chantel Ackerman understood how jokes worked. Sophia Loren’s Mara is the Call Girl To End All Call Girls. She’s intense, she suffers no fools, she negotiates high rates the way Chicano nephews try to get you to listen to their terrible Horrorcore mix CD. Watching Loren prowl her apartment complex feels like seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964. It’s a primal mission, it’s sublime devotion, it feels like fucking the Grand Canyon.

Her Daddy’s Boy Industrialist plays off her in the only way possible—riffing meekly. He can convince himself he’s in control, and in the most literal way he is—his lira helps pay her rent—but he cannot have her on his own terms. He must learn to live around her. And amazingly, he is not pathetic or Less of a Man for this, but simply being a good friend. Or client. They’re sort of the same.

Mara has a Meet Cute with a far younger seminary student, this poor kid ruled by a ridiculously traditional harridan. Sophia Loren’s immediate, violent hatred of this woman is funny, yes, but we feel it’s building toward upended expectations. Something must budge.

In the film’s best two scenes, Loren has an emotionally forthright conversation with the young seminarian, Roman pigeons providing chorus to the Excitement Of Discovery. How does De Sica know exactly where to place the camera? How do ant-like pedestrians feel equally as important?

Then, roughly 12 minutes later, the Religious Harridan comes to Loren’s door in tears. Her beautiful boy has given up on becoming a priest. Loren immediately gives in to her innate goodness and invites her in for coffee. Their conversation feels as intimate as between Five Decade Friends. How is De Sica so good at this?

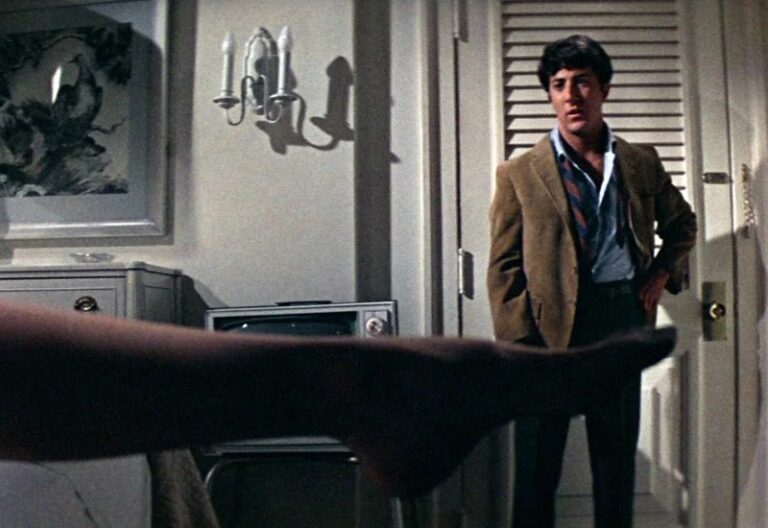

The Resolution itself isn’t terribly important. Just know that Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni reconcile, somewhat. It all ends on a strip tease that is incredibly hot, yes, but (I believe) enjoyable by everyone. It doesn’t feel like fodder for a particular Gaze. It’s more the consummation of an incredible woman’s story, done with a dude she finds somewhat annoying but essentially adores, a casual undressing with cabaret humor. Who could imagine anything better? I sincerely believe Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni were capable of the greatest sex Italy ever had.

Color has never been so kind to De Sica. I think that sucked some of the life out of Bicycle Thieves. This film is a pastel wonderland. The red-brown-green smudges on the sandstone walls have the messy intimacy of a paintbrush. It looks like a dripping painting. At some point, I paused the movie, tongued the LCD screen, and immediately knew; every movie should feel this voluptuous. You can taste the creeping wall peppers. You can smell the bubbling garlic. The salt of the Mediterranean pervades everything.

Life Magazine wanted to sell a “miracle,” but only De Sica could capture a vastly more beautiful reality.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

Middle-aged Giulietta grows suspicious of her husband, Giorgio, when his behavior grows increasingly questionable. One night when Giorgio initiates a seance amongst…

Anais is thirty and broke. She has a lover, but she’s not sure she loves him anymore. She meets Daniel, who immediately falls for her. But Daniel lives with Emilie – whom Anais also…

Miso lives from day to day by housekeeping. Cigarettes and whiskey are the two things that get her through the day. As cigarette prices and rent start to rise…

In the aftermath of World War II, Italy was a country in ruins, both physically and economically. Amidst the rubble and despair, a group of visionary filmmakers arose to…

Since the birth of cinema in the late 19th century, film has held an enormous cultural power. But with that power has come scrutiny — and often, suppression…

Tied to the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, feminist film theory critiques the portrayal of women in film, the male gaze, and the ways in which cinematic techniques…