midnight cowboy review

film by John Schlesinger (1969)

Envisioned on the picturesque coast of Southern California and based on the book of the same title, the collaborative efforts to put Midnight Cowboy on screen resulted in a 37-year-long love affair, the launching of careers, and a film that inherited an X rating for explicit content that in retrospect feels tame. It would also acquire seven Oscar nominations, winning three, including Best Picture. Its improvisational style meshed perfectly with its urban setting, influencing a generation of future cinema with its avant-garde execution and its refreshing and dogged avoidance of the glamour filmmakers had so readily relied on during the 50s & 60s.

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

Jun 05, 2024

These qualities serve to elevate and keep the film relevant more than 50 years later. Leaning into lived experience and impressing upon a younger generation the possibilities of cinema, Midnight Cowboy abandoned its allegiance to decadence and ego, exposing an ever-widening gap between generations of moviegoers and setting into motion a passing of the torch that brought in the new wave of Hollywood, forever changing the landscape of cinema.

From within the images of America’s disposed relics emerges Joe Buck (Jon Voight), an ambitious, optimistic, and naive hustler with a heart of gold, whose cowboy persona represents a caricature and re-emergence of America’s discarded past. Portrayed through the wonderfully effective and telling introduction, Schlesinger uses the long bus ride to New York City to introduce us to Joe through flashbacks of memories and scenes from his life back home. This gives the audience an immediate look inside Joe Buck’s past leading up to the present, which marks Joe’s arrival in New York. We find him on a voyage into the unforgiving environment of a colorful yet unyielding city in all of its glory and decay.

Immediately, we witness Joe completely out of his element as his southern charm and warmth fall upon the deaf ears of discerning skepticism characteristic of native New Yorkers. What ensues is a deconstruction of the American dream through the eyes of the lonesome cowboy—a “cowboy” whose identity has been built off the wisps of memories and culture that are no longer dominant, now obsolete and without influence in his new urban settings.

As Joe sets his sights on exploiting the laissez-faire attitude of a morally ambiguous city with a thriving economy in the indulgence of vice, we see the unfolding landscape of a sensitive and fragile psyche characterized by a need to be desired by women as a means of compensation for his subconscious feelings of inadequacy stemming from a sequence of abandonment manifested through various dream sequences of Joe’s past.

His confidence in his ability to attract women, which he feels is one of his only successful qualities, is overinflated and, like many other things about Joe, stems from his naive fantasy of an America that no longer exists but that Joe nevertheless feels people still desire. His precarious and exaggerated confidence, coupled with his naive obliviousness, makes him a lost and lonely human being looking for a deeper human connection fueled by his enduring and as yet woefully unfulfilled desire for belonging, acceptance, and love.

Flashbacks become the language that ties the bonds between Joe’s past and present, revealing how the idealistic and increasingly irrelevant image of the American cowboy became the template for Joe’s development in the absence of consistent nurturing and guidance. This simultaneously conveys an unhealthy childhood revealing neglect, abuse, and traumatic events that have led to a need for Joe’s independence and control over his own destiny, clearly showing a damaged interior being protected by his cowboy persona.

It isn’t until Joe Buck’s overconfidence finds him repeatedly being duped by those he means to hustle that he crosses paths with Enrico “Ratso” Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), a petty grifter with a limp like a wounded bird or injured alley cat who endures and survives in a calloused world. Joe and Rizzo’s acquaintance morphs into a codependency for survival, building an unlikely bond that transcends friendship amidst the grimy underworld of street hustlers and the dispossessed.

Through their platonic love, they begin to accept each other unconditionally, each gaining the other’s respect through their shared plights, hardships, and ultimately, their rejection by conventional society. It is in the squalor and despair of their day-to-day existence that Joe finds the deeper connection that supersedes his ambitions of becoming a gigolo. He is faced with the dilemma of his duty to his friend versus his desire to be admired and wanted by sexually unfulfilled wealthy women.

Joe’s caring and empathetic nature is repeatedly directed at those in need rather than himself. Even though he is a victim, he is still sympathetic to others. As his role shifts from pursuing the fulfillment of his childish fantasy to caring for an increasingly infirmed Rizzo, Joe’s vain aspirations begin to lose their luster, leaving him disillusioned with any hope for material success, belonging, or acceptance among the city’s upwardly mobile and elite.

We witness the transformation from a gullible boy to an authentic and earnest man when Joe finally sells his radio, his prized possession and only enduring connection to normalcy and hope, leaving him with nothing but a few dollars to get him and Rizzo through the day. Joe’s immutable personality speaks to his outsiderness and ignorance that has in turn slowly transformed into desperation through his moral struggles, where his past aversion to despair now resembles the urban grit that he so sharply contrasted—conveying the slow death of the human spirit.

Becoming a shadow of his former self, Joe’s search for an unattainable semblance of normalcy begins to wear him down as he abandons any illusions of making it in the Big Apple. But just as Joe’s aspirations vanish, Rizzo’s dreams of guiding Joe to success in Miami begin to illuminate new sparks of hope within both men, as Rizzo’s failing health has finally met its limitations.

With nothing left to lose, they set off to Florida. Selling his radio symbolizes one of the last remnants of normalcy and connection to his former self, but it is not until Joe discards his cowboy attire that he entirely sheds the illusions of his fantasies. Willing to expose his vulnerabilities instead of hiding behind the facade of his cowboy persona, Joe allows himself to be seen for who he is, like an exposed nerve or a child revealed to the real world for the first time.

Midnight Cowboy largely builds from its personality and atmosphere to effectively establish characters through the portrayal of emotion and the human condition, which are physically reflected in their settings. Colliding hope with despair as the intersecting crossroads of Joe Buck and Rizzo coexist in a contemporary world of excess and absurdity normalized amidst the chaos of it all while dismantling social and cultural boundaries. Luring its audience with its seductive mixture of ambiguity, realism, and gritty subtext while rendering a deeply sympathetic view of wayward lives, the film delivers a lingering perspective on the impact of meaningful relationships in the ever-alienating experience of human existence.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

With the strange disappearance of Laura, two colleagues, her older boyfriend, Rafael, and Ezequiel, learn of their recent discoveries, which may help…

In this classic thriller, Hans Beckert, a serial killer who preys on children, becomes the focus of a massive Berlin police manhunt. Beckert’s heinous crimes…

In 1943, Rudolf Hoss, commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, lives with his wife Hedwig and their five children in an idyllic home next to the camp. Hoss takes…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory…

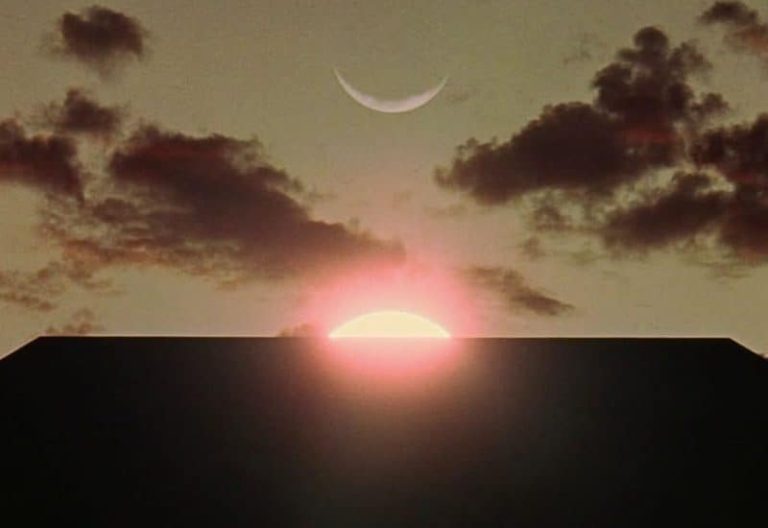

In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, until mid 1980s, a cinematic revolution unfolded in Hollywood that would forever change the landscape of the film industry…

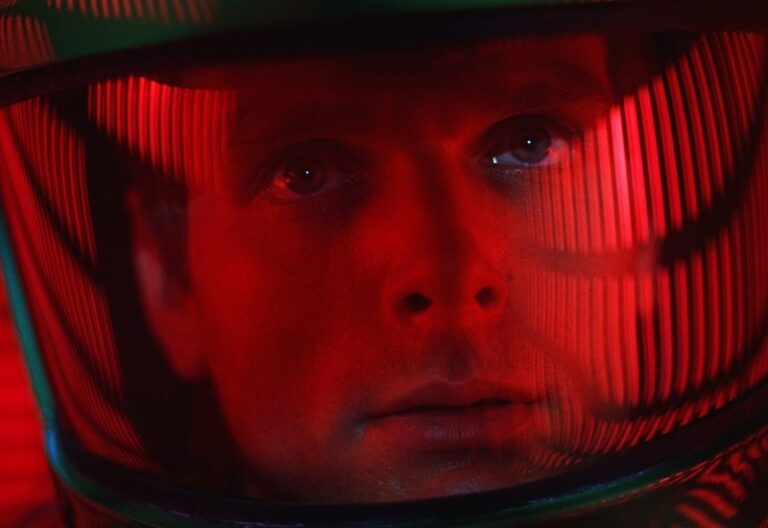

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…