m (1931) review

film by Fritz Lang

Peter Lorre, the face of Fritz Lang’s 1931 classic M, has always summoned a certain eerie charm for me. I remember watching reruns of “Looney Tunes” as a child and seeing caricatures of Lorre and other Hollywood faces that would periodically spring up. While most of the others’ faces would disintegrate into the background, Lorre’s unique physicality always made a distinct impression on my spongy 3-year-old brain. His unusual nocturnal trademarks, primordial eyes, and the unnatural sleepy cadence of his voice always embraced me with a chill, momentarily taking me out of the world of “Bugs and Daffy”.

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

July 29, 2024

As I came across Lorre’s films as an adult, depending on the character he was playing, those memories often added a subliminal layer within the film. None of them added more context than my initial viewing of M. Hans Beckert’s (Peter Lorre) presence, even though largely absent for the first half of the film, has always lingered within me as one of the most haunting characters in cinema, effectively challenging us to confront our own feelings about his character and empathize with his pathological transgressions in subversive ways during a time when heroes and villains were offered in traditionally black and white subtext.

Recognized for its modernist themes and broad display of technical achievements, putting it far ahead of its time, M is one of those special films that has found itself at the forefront of various crossroads of cinematic and historical significance. Including modernism, German Expressionism, WWII, Hitler’s rise to power, film noir, police procedurals, and early examples of the serial killer phenomenon, further adding to its relevance and interest.

The first of Lang’s films utilizing sound, with already a dozen or so titles under his belt as a director, M remains one of his most revered and a classic piece of 20th-century cinema. Shot in 6 weeks and released at the precipice of the Weimar Republic before Hitler came to power, Germany was in the midst of an economic recession, a thematic thread woven into the core of the film’s despairing tone.

From the film’s opening sequence of Elise Beckmann and her friends playing, seen from an overhead shot, we hear them singing nursery rhymes. At the same time, Elsie’s mother observes from a balcony above as she comments on the song’s macabre sentiment, which stands as a foreshadowing moment of things to come. Any frivolity that may have lent itself to the images of children playing is quickly dissolved. The film uses visual grammar to emphasize the importance and passing of time through symbolic imagery blended between her waiting mother at home and young Elise as she wanders aimlessly down the street with a ball.

M’s opening sequence is an achievement in itself, rivaling some of my favorite openings of all time, such as “Once Upon a Time in the West” and “Touch of Evil,” immediately placing its viewer into the film’s drama. Removing any displays of violence, it relies on visual imagery and audio cues to hint at the violence and murder. Using objects like the child’s ball or a balloon to signify tragic events demonstrates the expanded mechanics and technical inventiveness, including M’s whistling that early on serves as a makeshift version of Pavlov’s law and an audio cue to establish his cinematic presence on and off the screen until he is properly introduced in the film.

Arriving at a “wanted” poster for a murderer, a looming figure steps in again from above, this time as a shadow confronting Elsie, establishing to the audience that this shadow is one of predation and the very one depicted on the poster. The sequence of events that follows sets up Elsie’s murder, depicting shots of an abandoned ball and a floating balloon, two objects previously associated with Elsie, as the murderer is mostly perceived through his whistling while being largely obscured. At the same time, her mother anxiously looks on, depicting absent spaces normally occupied by her daughter. Within these few short minutes, a tangible sense of urgency is communicated, interspersed with a technical efficiency that translates flawlessly into a ratcheting sense of alarm as the paperboy exclaims news of the crime, prompting the public’s frenetic reaction.

Standing as the precursor to the serial killer and police procedural genre, only a few films, such as Alfred Hitchcock’s 1927 film “The Lodger,” predate M by a handful of years. Its connection with this genre can be largely attributed to the real-life crimes of Peter Kurten and Fritz Haarmann, prompting a systemic link to a growing preoccupation with and interest in murder and tragedy.

M stands as a study of fear and the mental degradation of the individual and society as a whole, where negligence and individualism play contributing roles. Beckert’s rage and alienation suggest a link to his character as a direct byproduct of urban life stuck in economic despair and stand as a pensive commentary on our culture of violence and moral nihilism upheld and allowed to thrive through urban living.

When we are given our first look into Beckert’s psyche, we get a confounding window into a conflicted mind where he struggles internally to save himself from himself. Beckert’s internal struggles are a transcendent moment, forging some modern themes into the film where we are confronted with asking ourselves, “Whose side are we on?” Sympathizing with the murderer may have felt like a betrayal to some of the audience and the film’s characters in the 1930s. In modern cinema, it is commonplace, but it remains a subversive move during its era and is one of the many layers that make M such a beautifully conscious work.

One of the film’s unusual choices is that it detours from the notion of a “whodunit?” mystery from the audience’s perspective, as it immediately establishes Beckert, who has a pervasive influence over the city, as the murderer. Through sprawling navigation, it surveys the city’s corruption and indifference as they conduct their search amongst smoke and shadows, intersecting between the police, politicians, and criminals.

The film links the different groups and settings through their mutual pursuit, skillfully intersecting their social spheres and representing each group by class and social status. This mutual motivation further solidifies the city’s social ruination, exemplifying that all walks of life have been consumed with self-interest.

It increasingly comments on the sociological parallels of criminals, cops, and politicians, defining the different social groups who all share a desire for Beckert’s apprehension, though not because they are beholden to a cultural responsibility or a code of ethics. Instead, it exemplifies our own social disorders, which abound from a lack of checks and balances observed through our economic anxieties, power, and greed. Dispelling a unified order influenced by collectivism and principles, it instead shapes a darker society diversified by class yet mutually motivated by individualism and economic gain.

M continually demands our engagement to reach further and can, at times, be seen as a premonition of the Second World War and German and European politics. Lang highlights the public’s fear through perverse distortions that act as a contagion, infecting everything it comes in contact with. A public that is constantly at the ready projects its own prejudices, paranoias, and suspicions about any target that finds itself under the canopy of its biases.

Looking to visualize something that does not exist in reality except in our minds of boogeymen, witches, and wolves, we see the murderer on every street corner and human face. A face that, ironically, was able to hide amongst the masses undetected by all our fears until the symbolic and mythological blind seer identifies him through his trademark whistle.

The perpetrator’s acts are overshadowed by society’s actions at large and mob mentality. A kangaroo court stands not as a pinnacle for justice but as a method of redemption and vengeance, displaying our own vile instincts in which we as a society have perverted justice to circumvent the very act itself from serving the target of our own aggressions. Fritz Lang’s M applies a realist lens to the human condition and the duality of humankind.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

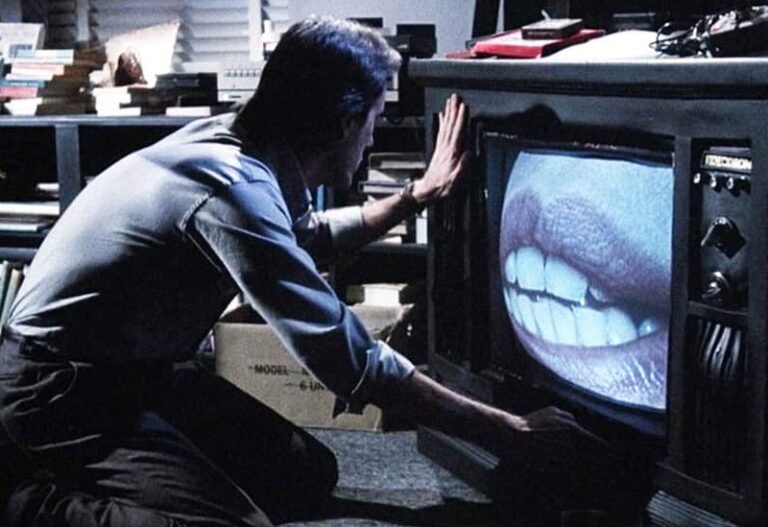

As the president of a trashy TV channel, Max Renn is desperate for new programming to attract viewers. When he happens upon “Videodrome,” a TV show dedicated…

When a car bomb explodes on the American side of the U.S./Mexico border, Mexican drug enforcement agent Miguel Vargas begins his investigation, along with American police…

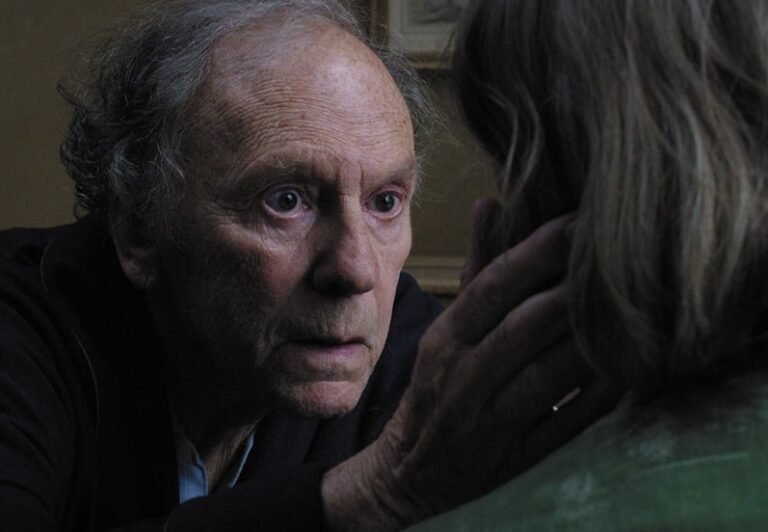

Georges and Anne are in their eighties. They are cultivated, retired music teachers. Their daughter, who is also a musician, lives abroad with her family. One day…

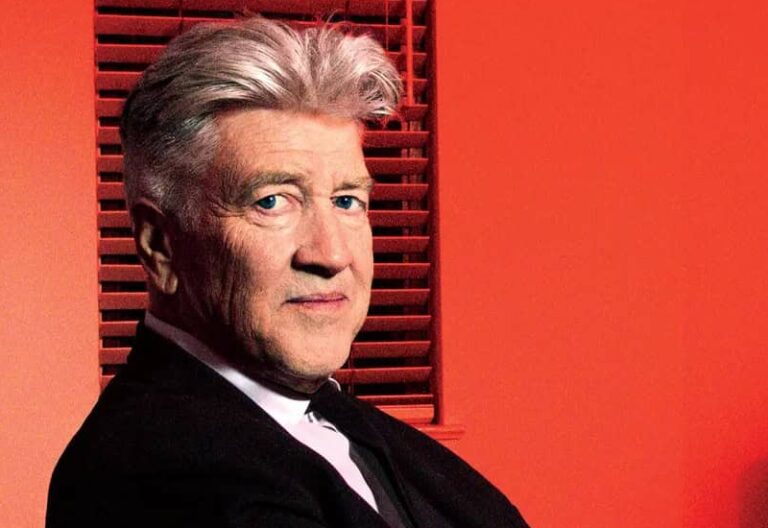

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory…

German Expressionism stands out as one of the most distinctive styles in the era of silent film. Expressionism, as an artistic movement, originally emerged…

Neo noir is a contemporary style that draws from the classic film noir genre from the 1940s and 1950s. Classic film noir became known post-World War II, characterized by…