godland review

film by Hlynur Palmason (2022)

Inspired by early photographs taken in Iceland, which tell a story of historical fiction, Godland serves as a palette upon which colonial rule and religious dominance were commonly inflicted. Depicted through its precise use of technicality, this remarkable and highly POV experience involves most of what we observe through the eyes of a Lutheran priest and the lens of his camera, which inadvertently become one and the same, creating a metaphorically and symbolically expressive poetry.

Review by: Aaron Jones | Filed Under: Film Reviews

January 28, 2024

Iceland generally only produces a few dozen films a year, a grand achievement compared to the ’70s and ’80s when their output rarely surpassed 4-5 films, many of them shorts. Their film industry is repeatedly making its way into my cinematic memory, and two of those reasons are due to the collaboration between cinematographer Maria von Hausswolff and director/writer Hlynur Palmason, who have worked together on 5 projects.

Their collaborative works communicate the climate of Iceland through the serpentine presence of its uniquely isolated geography and characteristics that differ from what most viewers call home. These elements are immediately inviting in cinema because I am placed in an environment I know very little about, which is a sure way to inspire my curiosity.

Their films don’t take the natural landscapes for granted unless it is to develop a character and show that even with the convenience of the modern age, the characteristics of their homeland are an insurmountable factor that affects their daily lives physically and mentally. There is a symbiosis of bleakness and alienation within their films that seems symbolic and fitting of the atmosphere, which I find to be one of the many alluring components that resonate with a feeling of intimacy through storytellers deeply connected with the land they so methodically portray.

In the late 19th century, Iceland sought independence from Danish rule and the Kalmar Union. The dominant force of Denmark viewed itself as the template for virtue, morals, and superiority. A view represented by Lucas, a Lutheran priest sent to Iceland under Danish rule to supervise and build a new parish church, get to know the people, photograph and document the Icelandic inhabitants and landscapes during his travels, while unwilling to learn and embrace the Icelandic culture himself.

As Lucas journeys through the Icelandic wilderness with the help of his guide Ragnar and his companions, we see a fearful man out of his element in the unforgiving and harsh open landscapes which takes a toll on his morale and his faith. A wilderness of glaciers, mountains, and volcanoes serve as representations of our insignificance in the face of the natural world.

As we see him learning to ride a horse, Lucas is resistant to the directive of giving the reins some slack, which serves as a metaphor for his relationship dynamics, most notably, his need for absolute control. He carefully illustrates self-induced alienation, never humbled by his own outsiderness, and never eager to learn, even when doing so would be the path of least resistance. The embodiment of arrogance, he perceives anyone outside the influence of God and Denmark as an outsider, even in their own land, meeting them with condescension.

Becoming increasingly aware of his emotionally withdrawn persona, which borders on misanthropic, Lucas puts aside his efforts to deny solidarity with his guide and the locals and instead focuses on photographing the gorgeous open wilderness captured by exquisite cinematography. Shot in a 1:33.1 ratio, the wet-plate photo frames that Lucas captures throughout the film share similarities with the first-ever photographs of Iceland, which served as the inspiration for this film.

As the layers begin to be peeled away, we see what Lucas sees: a beautiful land country without recognition or acknowledgment of its inhabitants as equals, but only as mere obstacles set in place to help him reach his physical and spiritual destination. Obstacles he approaches much like his photography to be manipulated and altered to his desire.

A destination he believes he must reach because God has chosen him and his faith. Lucas demonstrates an entitlement that fuels his arrogance and his nationalistic mindset, reinforcing his air of superiority and prejudiced belief that there is nothing the Icelandic people possess that has value or worth learning.

Lucas’s survival increasingly depends on the knowledge and kindness of the Icelandic people who save his life and embody a stoic humility completely alien to the priest. Lucas sees his survival as an act of God inherited through his blind faith and shows neither recognition nor gratitude. The film’s tone shifts midway, evolving into a character study of simmering personalities all under the veil of Colonialism and religious superiority.

We are constantly reminded of the ugliness of human behavior and religious hypocrisy throughout history while surrounded by the ominous beauty and melancholic score of the traditional songs of the locals. We see how Lucas’s faith in religion acts as an impairment and disconnects him from those outside its influence. Perpetually reinforcing division, the tone-deaf priest never considers it a hindrance but rather a jewel unable to be seen or valued through primitive eyes.

Arrogantly claiming ownership of civilized progress yet seeing the world through the eyes of a preordained design and self-imposed narrative, much like the subliminal grammar within the film comparing Lucas’s reliance on photography and religion as a language to translate the order of the world. His version of the world is propped up by a baseless artificial structure and ideology that is only given credence by the power gained from its subjects within its authority to project their perceived concepts and ideologies upon them.

Author

Reviewed by Aaron Jones. Based in California, he developed a passion for film from a young age and has since viewed over 10,000 films. His appreciation for the medium led him to film criticism, where he now writes for CinemaWaves, offering analysis of both contemporary releases and timeless classics. In addition to his work here, he has contributed to other publications as well. Feel free to follow him on Instagram and Letterboxd.

In a bustling Mexican household, seven-year-old Sol is swept up in a whirlwind of preparations for the birthday party for her father, Tona, led by her mother, aunts…

Following the everyday lives of a group of young theater performers from rural Fenyang, spanning the late 70s to the early 90s in the aftermath of China’s Cultural Revolution…

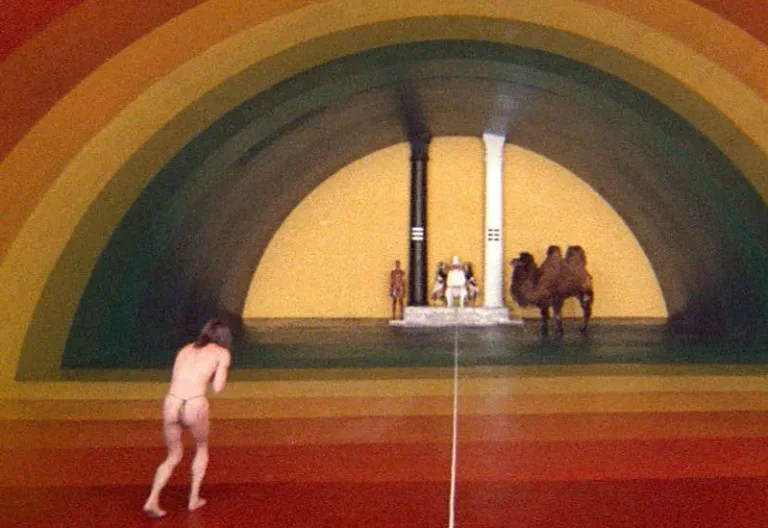

The scandal of the 1973 Cannes Festival, director Jodorowsky’s flood of sacrilegious imagery and existential symbolism in The Holy Mountain is a spiritual quest for…

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…

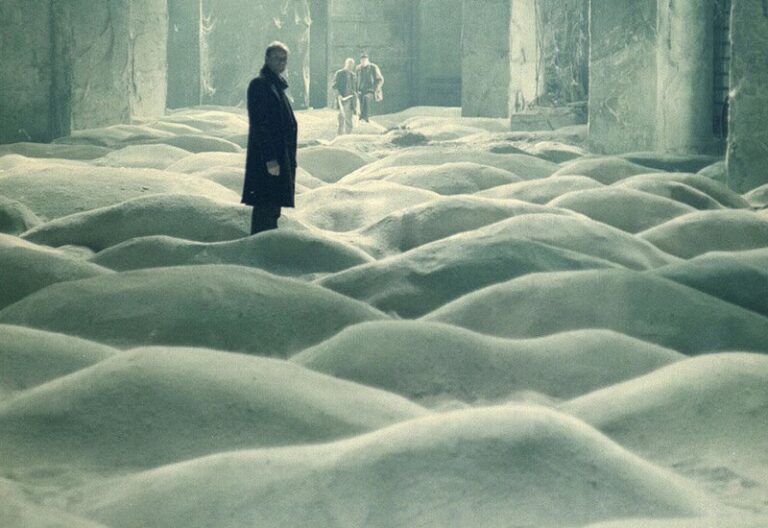

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its contemporaries…

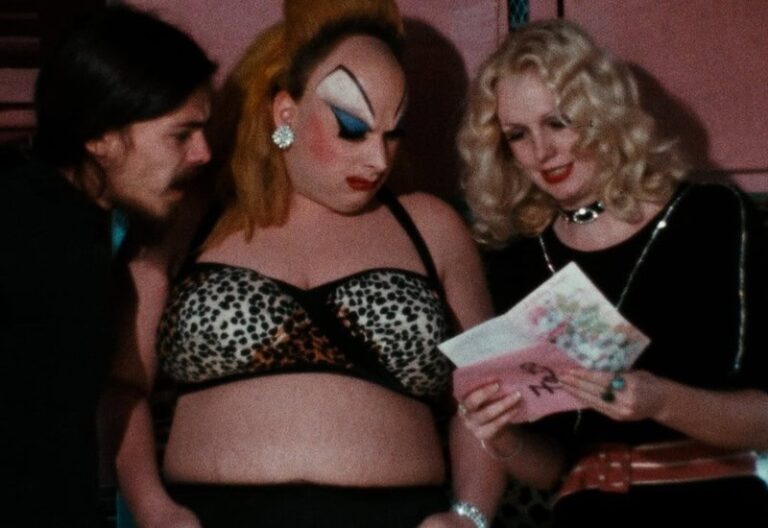

A cult film is a movie that builds a devoted following without achieving mainstream success or widespread critical praise at the time of its release. These films are…