an introduction to agnès varda

In The Beaches of Agnès, there is a scene in which Agnès Varda looks down the lens of her camera, straight at her audience, and says: “If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes. If we opened me up, we’d find beaches.” This quote resonated within her work for decades. Beyond the beaches, Varda’s approach to filmmaking tackled the complex relationship between people and place.

Written by: Inés Cases-Falque | Filed Under: Film Blog

Who are we, as communities and individuals, without the places we come from, we grow up, or intend to go to? To Varda, her camera was the canvas, and the people and place in front of her were the colours swirling together to paint how she saw humanity.

There is a constant game of tug-of-war in Varda’s career. Whilst today she remains as one of the most overlooked figures of the French New Wave movement, her role as a pioneer and leading voice during the era cannot be overstated. Varda surrendered herself to filmmaking in every way an auteur can; she let herself live in front of the camera, and encouraged ordinary people to do the same, shifting the idea that film, as an artform, was only accessible to glamorous starlets and rigid direction.

Grounded in an experimental approach, she layered her narratives with social commentary and feminist premises, the latter of which was rarely considered in an industry that was, and still is, overwhelmingly steered by men. But it’s also worth noting that her approach to this topic was seldom confrontational, as she preferred to invite her audience in a cinematic space that posed questions and teased with the answers in an almost playful manner.

Varda’s persistent ambition was to achieve accessibility; oftentimes, her films, documentary and fiction alike, were simple and uncomplicated, but layered in the way she experimented with editing techniques, colour, and perspective. Her films are personal, but direct in their approach, leaving its audience to scratch beneath the surface themselves and question their own existence.

Career beginnings and La Pointe Courte (1955)

Unlike many auteurs of her era, Agnès Varda didn’t grow up enamoured by the movies. She knew little about the medium, and in her early twenties, felt more drawn to photography and art history, which she studied and practiced in Paris. In fact, it’s said she had only seen a little over a dozen films by her mid-twenties. It’s perhaps her lack of cinematic influence that initiated her abstract approach to filmmaking, one that prioritised stillness, location, and cinécriture, setting her apart from her peers during the French New Wave.

Whilst the rejection of polished studio productions was a key element to this turning point in French cinema, it was Varda who pioneered the idea of blending documentary and fictional elements in her filmmaking.

Her feature debut, La Pointe Courte (1955), predated the New Wave, but it included many elements that would later become vital to New Wave filmmaking, a mark of Varda’s innovation. French film critic Georges Sadoul noted the film’s revolutionary approach, citing it as “truly the first film of the nouvelle vague”.

Filmed in Sète, a small fishing town in Occitanie, Varda combined a fictional story between a married couple, and a documentary-style narrative about the townspeople. Weaving together reality and fiction, Varda used real-life footage largely inspired by her own photography collection of Sète, a town she spent a large part of her adolescence in during the Second World War. Her personal connection to the town inspired the story, as she handles each image as if it were a home video, or a moving photograph from a holiday scrapbook.

Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

Cléo from 5 to 7 remains Varda’s most famous feature, and for good reason, as it premiered amid the popularity of the New Wave. Set in Paris, where Varda lived at the time, the film follows its protagonist, Cléo, as she wanders around the city waiting for the result of a potential life-changing diagnosis.

Mortality was a theme often present in Varda’s filmography, and existentialism became a vital philosophy unpacked by many of her peers at the time, but Varda’s lens also feels deeply feminist in its approach.

As Cléo wanders around Paris, interacting with the city and the time slipping through her fingers, there’s a newfound sense of agency that she gathers on her journey. Portrayed by Corinne Marchand, a glamorous figure in French pop culture, Cléo is less concerned by her physical appearance and more so by her interactions with people and the place she occupies. She feels her own vitality, which may be taken away from her in the coming hours, and savours it.

Shot on location, Cléo from 5 to 7 remains an essential film within the era. Varda’s use of jump-cuts, narration, chapter divisions, makes her audience readily aware that they are watching a constructed piece of media, without diluting her message. Cléo is given a voice, an angle, and a literal perspective through the lens. She is not a subject to be ogled at, but a character with her own agency.

Le Bonheur (1965)

Varda revisited feminist filmmaking in many of her works, but it’s perhaps Le Bonheur that emerged as her most divisive. Upon its release, it was labelled as grossly unfeminist, since Varda’s approach seemed to prioritise the perspective of her male protagonist. The film follows a married couple who seem to lead a perfect life with their two children, until the husband meets a beautiful post office worker and becomes enamoured with his new mistress.

The narrative is deeply unsettling, filmed in a more detached and impersonal way compared to her previous works, as her use of bright colours muddies the tone and urges its audience to scratch beneath the vibrant surface.

The use of colour, which is absent in her previously mentioned works, is purely artificial, as is the happy-go-lucky score which plays over many familial scenes. The façade of a happy family slowly dissolves into the affair that changes the dynamic, but the colours remain, as we come to realise that the husband is unaffected by his unfaithfulness.

It speaks to his ego, his lack of empathy, and eventually, his wife’s own demise. She is quickly replaced by his mistress, who takes on the role of housewife, and we are left to wonder if she too will be swiftly replaced by another in time.

Varda asks its audience if the role of the housewife is sustainable to a woman’s character, and if the housewife trope is ethical at all. She effectively uses juxtaposition to position the husband as an antagonist, and his first wife as a victim of her own replaceability in the household.

Vagabond (1986)

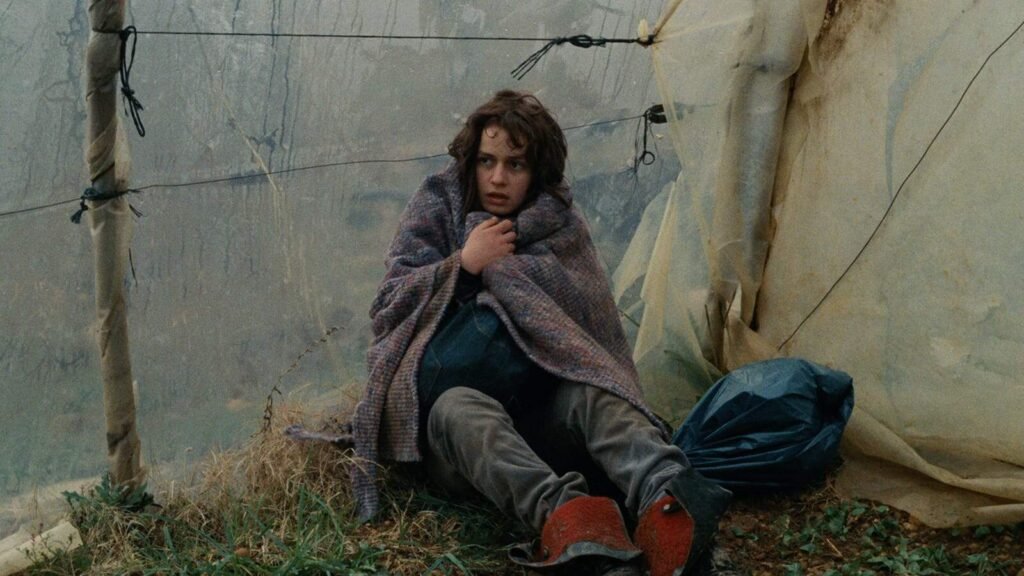

This hybrid approach to filmmaking continued long into her career, and it is perhaps most notable in Vagabond (1985), which saw a young Sandrine Bonnaire in one of her most notable leading roles. The film follows a young homeless woman called Mona, as she tries to survive in the French countryside during the cold winter months.

It’s worth noting that Mona was not born into poverty but was a secretary in Paris who became disillusioned with her life and decides to live on the streets to find a new purpose, or rather, no purpose at all within society. Once again, Varda questions the role of women in France, inviting her viewers to dissect how they are regarded within these female-orientated roles.

This film differs from the others mentioned, noting a slight change in Varda’s approach at the time, as she used a more fragmented approach to construct the story. For example, the film opens on Mona, lying dead in a ditch, covered in frost and ice. Her whole story is told in flashbacks; with snippets of the people, she interacted with on the road before her demise shown in police-style interviews.

Varda used non-actors to play these roles, highlighting her commitment to grounding her work in cinérealité despite the fictional story. Bonnaire herself didn’t wash her hair for months during filming, and performed all the rough stunt work herself to fully immerse herself in the role.

This pseudo-documentary style of filmmaking was what set Varda apart from others, especially nearly a decade after the end of the New Wave. I would argue that Varda positioned her audience similarly to the people being interviewed in the film, as they too observed Mona’s demise, and would later recount what they saw when they left the movie theatres.

Conclusion: The Mother of

the French New Wave

The French New Wave prided itself in its authenticity, and yet, few came closer to capturing the authentic than Varda. Though her Oscar-nominated documentary, Faces Places (2017), did reawaken some interest in her past works, it wasn’t until her passing in 2019 that cinephiles and critics turned their heads towards the collection of cinema gems she left behind.

Agnès Varda celebrated life in all of its complexity, colour, and contradiction. To revisit her films is to rediscover the world through her eyes: curious, compassionate, and always searching for meaning in the seemingly mundane. Hers was a lens that never stopped asking questions, and in doing so, opened the door for generations of filmmakers to follow.

Author

Written by Inés Cases-Falque. A passionate film academic, writer, and cinephile who has contributed as a writer to blogs and film journals since her graduation. A founder, writer, and leading editor for Lancaster University’s CUT TO Film Journal, she mainly takes interest in the French New Wave, Nordic cinema, Japanese horror, and post-Franco Spanish political cinema. You can follow Inés on Instagram and Letterboxd.

Or La Nouvelle Vague, is one of the most iconic and influential film movements in the history of cinema. Emerging in the late 1950s and flourishing throughout the 1960s…

The studio system was a dominant force in Hollywood from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was characterized by a few major studios controlling all aspects of film production…

Jacques Demy appeared at the height of the French New Wave alongside contemporaries like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. Demy’s films are celebrated for their visual…

Tied to the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, feminist film theory critiques the portrayal of women in film, the male gaze, and the ways in which cinematic techniques…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory suggests…

Mise en scène is a French term that means “placing on stage” and encompasses all the visual elements within a frame that contribute to the overall look and feel of a film. Originating…