introductory guide to metacinema

Metacinema, also known as metafilm, is a style of filmmaking that reflect on the nature and structure of cinema itself. It involves works that draw attention to their own construction, question the boundaries between fiction and reality, or explore the role of the filmmaker and the audience in the cinematic experience. In essence, metacinema is cinema about cinema.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

What Does "Meta" Actualy Mean?

The word meta comes from the Greek term meaning “beyond” or “after,” and in storytelling, it refers to self-awareness within the work. When something is meta, it doesn’t just present a narrative—it acknowledges that a narrative is being told. In cinema, this means a film might reflect on its own construction, question its relationship to reality, or make the audience aware they’re watching a movie.

In this sense, they uses meta techniques to challenge traditional cinematic conventions. Characters may recognize they’re in a film, stories may reference their own creation, or the movie might call attention to editing, performance, or genre tropes. This self-referential approach invites the viewer to think critically about how stories are made and why we respond to them.

Historical Development

of Metafilms

The development of metacinema started in the early 20th century, when filmmakers began to experiment with the medium. Silent films like “Sherlock Jr.” (1924) by Buster Keaton represent early examples of metacinema. In this film, Keaton plays a projectionist who dreams himself into the movie screen, creating a playful interaction between the world of the audience and that of the film. This blending of fiction and reality laid the groundwork for later developments in self-referential cinema.

During the post-war period, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, metacinema became more prominent with the rise of modernism and film movements like the French New Wave. Directors such as Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut frequently used techniques to disrupt narrative flow and provoke the viewers. This period subsequently marked a turning point. A prime example of metacinema from this era is Federico Fellini’s classic “8½” (1963)—an introspective tale about a director struggling to make a film, which blurs the lines between reality, memory, and imagination.

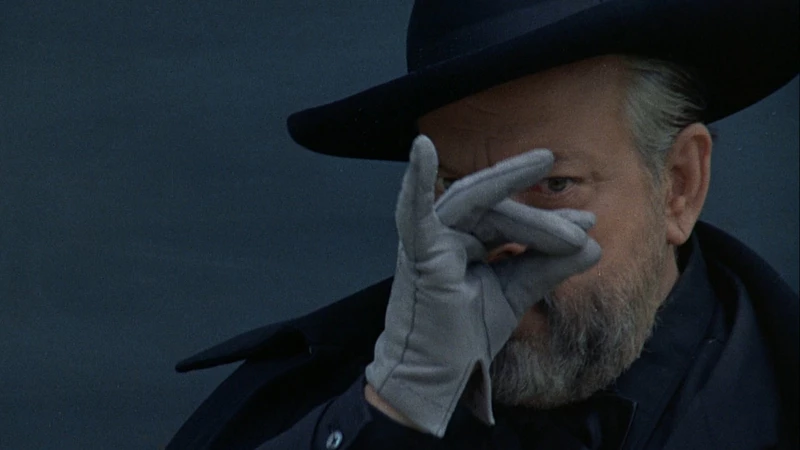

The 1970s and 1980s continued this trend with a more postmodern approach. Filmmakers like Woody Allen and Orson Welles expanded the language of self-referential cinema, with films such as “The Purple Rose of Cairo” (1985) and “F for Fake” (1973). While Allen explored the interaction between fictional worlds and reality, Welles took a more experimental route—F for Fake cleverly blurs the line between documentary and fiction, using editing and narration to examine themes of authorship, illusion, and the nature of truth in storytelling.

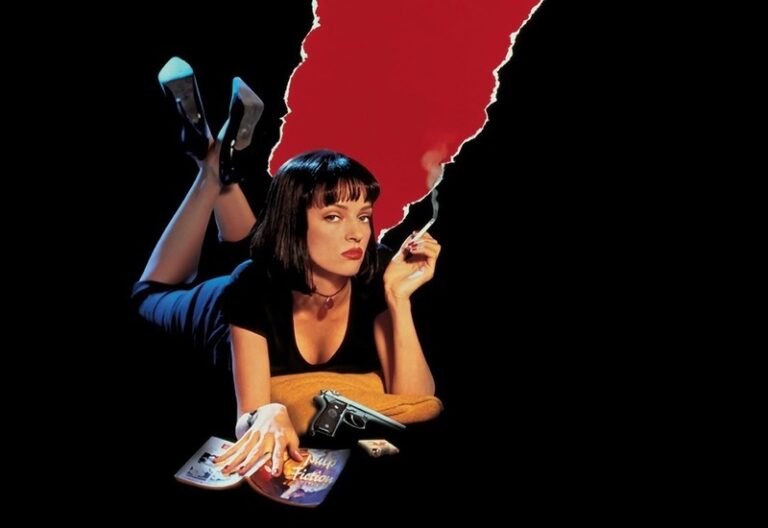

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, metacinema gained even more traction with the rise of digital technology and a more media-savvy audience. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Wes Craven, and Spike Jonze crafted works that deliberately referenced film history, genre tropes, and audience expectations. The emergence of the internet further encouraged self-awareness and irony in storytelling, making metacinema an increasingly common tool in contemporary cinema.

Characteristics of Metacinema

Breaking the Fourth Wall: Characters may speak directly to the audience, acknowledging their existence within a film. This direct address disrupts immersion and invites viewers to reflect on the constructed nature of the narrative.

Film-Within-a-Film: A common device where a movie includes another movie being made or watched, creating a layered storytelling experience. This structure draws attention to the processes of filmmaking itself.

References to Film History or Conventions: Metacinema frequently engages with genre clichés, cinematic tropes, or specific homages to classic films.

Exploration of Authorship and Identity: Many films reflect on the creator’s role, using surrogate characters or autobiographical elements to explore artistic intention and self-expression.

Narrative Disruption: Metacinematic works often feature non-linear storytelling, sudden shifts in perspective, or deliberate confusion between reality and fiction.

Famous Examples of Metafilms

“8½” (1963) – Federico Fellini: One of the most influential films ever made, 8½ follows a film director experiencing creative block as he struggles to make his next movie. Blurring memory, fantasy, and reality, the film becomes a surreal reflection on the artistic process, filled with self-referential moments that question the purpose and meaning of cinema itself.

“F for Fake” (1973) – Orson Welles: In this playful blend of documentary and fiction, Welles explores the nature of authorship, illusion, and truth through the lens of art forgeries. Constantly breaking the fourth wall and manipulating the audience’s expectations, the film acts as both a trick and a commentary on the power of storytelling.

“The Truman Show” (1998) – Peter Weir: Truman Burbank’s seemingly perfect life begins to unravel when he discovers that he’s the unwitting star of a global reality TV show. As he becomes aware of the artificial world around him, the film explores themes of surveillance, authenticity, and the ethics of entertainment—posing deep questions about performance and spectatorship.

“Adaptation” (2002) – Spike Jonze & Charlie Kaufman: A screenwriter struggles to adapt a nonfiction book and ends up writing himself into the story. This layered narrative examines the difficulties of creative expression while folding real-life figures into a fictionalized structure, blurring the boundaries between author and character.

“Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” (2019) – Quentin Tarantino: Set in 1969 Los Angeles, Tarantino’s film is a metatextual homage to a bygone era of filmmaking. By reimagining real historical events and inserting fictional characters into Hollywood’s mythos, the film reflects on the cultural power of cinema and the stories we choose to remember—or rewrite.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

Postmodernist film emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, rooted in the broader cultural and philosophical movement of postmodernism. It started as a reaction to the…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory suggests…

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…

Juxtaposition is a powerful storytelling technique where two or more contrasting elements are placed side by side to highlight their differences or to create a new, often more…

Experimental film, referred to as avantgarde cinema, is a genre that defies traditional storytelling and filmmaking techniques. It explores the boundaries of the medium, prioritizing…

Film criticism is an essential part of cinema, serving as a bridge between filmmakers and audiences. It focuses on analyzing, evaluating, and interpreting films, while providing…