korean new wave

est. late 1990s – now

The Korean New Wave reshaped South Korean cinema, earning both local and international acclaim. Characterized by a departure from conventional filmmaking, it introduced a wave of innovative, diverse, and socially aware films that reshaped the industry.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Movements

Origins of the Korean New Wave

The late 1980s and early 1990s marked a pivotal moment in South Korea’s political and cultural evolution, as the nation underwent significant democratization following years of authoritarian rule. This shift brought political reforms with the lifting of strict government censorship, which had long suppressed artistic expression. Filmmakers, now free from the constraints of state-imposed limitations, found a new sense of creative liberation that allowed them to explore socially relevant themes.

In tandem with political change, South Korea experienced rapid economic growth during this era, known as the Miracle on the Han River. The country’s newfound prosperity extended into the arts, as increased funding flowed into the film industry. With greater financial backing, filmmakers could pursue more ambitious projects, experiment with new styles, and increase production values, leading to a renaissance in South Korean cinema.

Simultaneously, urbanization and modernization were transforming South Korea’s society, while the influx of Western cultural influences contributed to a more globalized outlook. These shifts resulted in a cultural landscape that was increasingly complex and multifaceted. South Korean filmmakers began to reflect this evolving reality by addressing themes that resonated with the changing society – exploring contemporary Korean identity, the clash between traditional and modern values, and the generational conflicts emerging in the rapidly urbanizing nation.

Characteristics of the Korean New Wave

The Korean New Wave is characterized by its exploration of diverse and complex themes, often delving into societal issues, historical traumas and the intricacies of human condition. Many films examined the complexities of family dynamics, shedding light on the hidden tensions, and emotional struggles concealed within Korean households. A recurring theme in the New Wave cinema was the critique of social disparities, illuminating the lives of the marginalized, and prompting viewers to confront issues of inequality and injustice.

Revenge served as a powerful motif in numerous films, highlighting the moral ambiguity surrounding the pursuit of vengeance. Certain directors, notably Park Chan-wook, incorporated visceral violence and psychological depth into their work. This departure from standard storytelling norms contributed to the “edgy” and unconventional nature of the Korean New Wave.

Numerous films explored themes of cultural identity, tradition, and the clash between old and new in South Korea. The tension between tradition and modernity became a rich source of storytelling.

Important Korean New Wave Films and

Directors

Renowned for his visually striking and psychologically intense films, Park Chan-wook gained international acclaim with works like “Oldboy” (2003) and “The Handmaiden” (2016). His films usually feature themes of vengeance, morality, and human nature with the unique blend of style and substance.

Bong Joon-ho’s films, including “Memories of Murder” (2003), and the Academy Award and Palme d’Or-winning “Parasite” (2019), exemplify his versatility and social commentary. Bong’s ability to blend genre elements has made him a central figure in South Korean cinema.

Known for his unconventional and often provocative films, Kim Ki-duk delves into the darker aspects of human nature. “Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring” (2003) and “3-Iron” (2004) are notable examples of his contemplative and visually striking work. His approach to filmmaking has earned him both acclaim and criticism, making him one of the most enigmatic figures in cinema.

In addition to these three filmmakers, Lee Chang-dong, with films like “Peppermint Candy” (1999) and more recent “Burning” (2018), offers poignant social commentary through meticulously crafted narratives, and are celebrated for their exploration of relationships and human behavior.

Global Recognition and Legacy

The Korean New Wave gained massive international acclaim, with South Korean films finding success at major film festivals and attracting a growing global audience. Directors like Bong Joon-ho achieved milestones by winning prestigious awards, including the Palme d’Or at Cannes and multiple Oscars for “Parasite.” The movement changed perceptions of South Korean culture on the global stage, generating interest in Korean cinema, and paving the way for increased cultural exchange. South Korea’s film industry became a key player in the global market, influencing filmmakers worldwide.

As its Asian predecessors Hong Kong and Taiwanese New Wave, it stands as a cinematic revolution that not only revitalized South Korean cinema but also contributed significantly to the diversity and innovation of Asian and global filmmaking. Through its unique storytelling, thematic richness and international success, the movement has cemented its place in the history of cinema.

Refer to the Listed Films for the recommended works associated with the movement. Also, check out the rest of the Film Movements on our website.

Emerging in the late 20th century, a film movement known as the Hong Kong New Wave, originating from the bustling neon streets of Hong Kong, while captivating global…

In the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, until mid 1980s, a cinematic revolution unfolded in Hollywood that would forever change the landscape of the film industry. American New..

Taiwan New Wave, also known as Taiwan New Cinema, was a film movement that flourished during the 1980s and 1990s. It gained international acclaim for its exploration of complex…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…

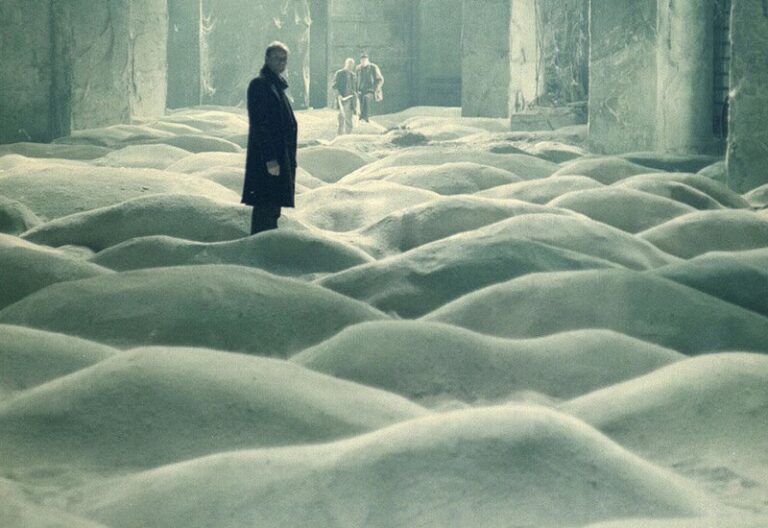

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…