inside the polish school of posters

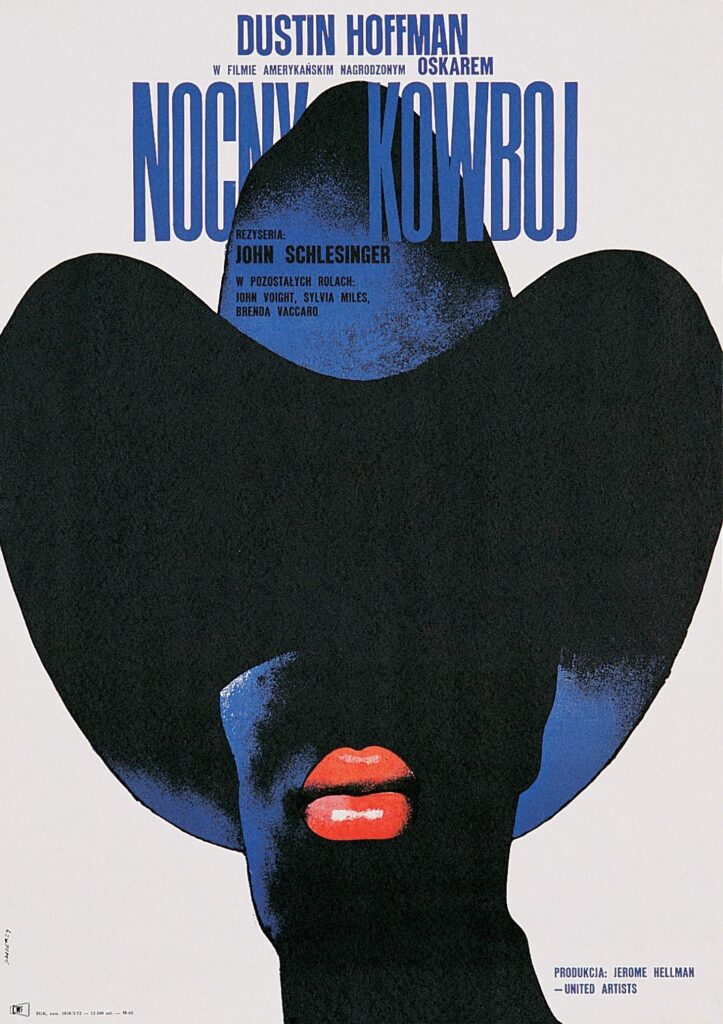

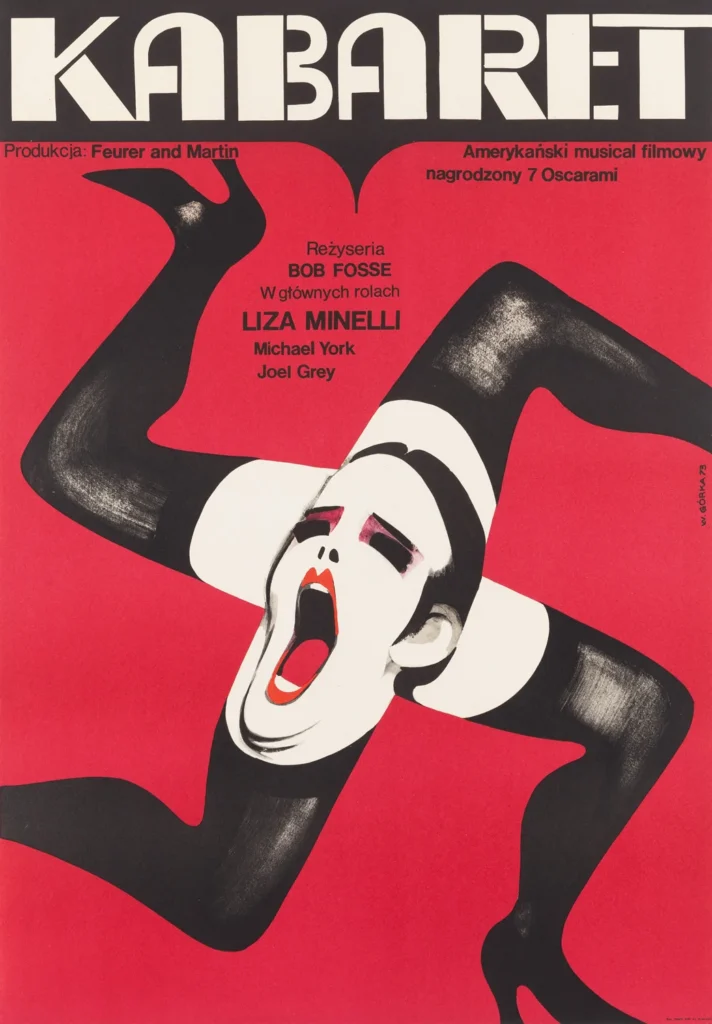

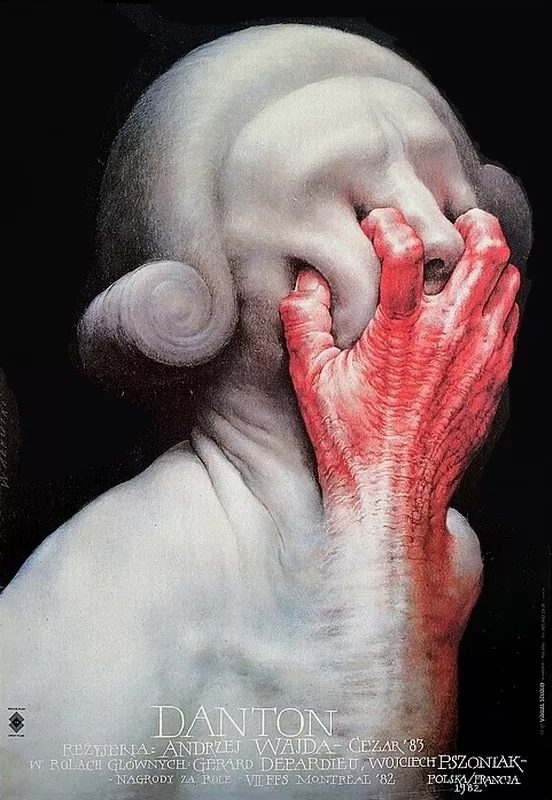

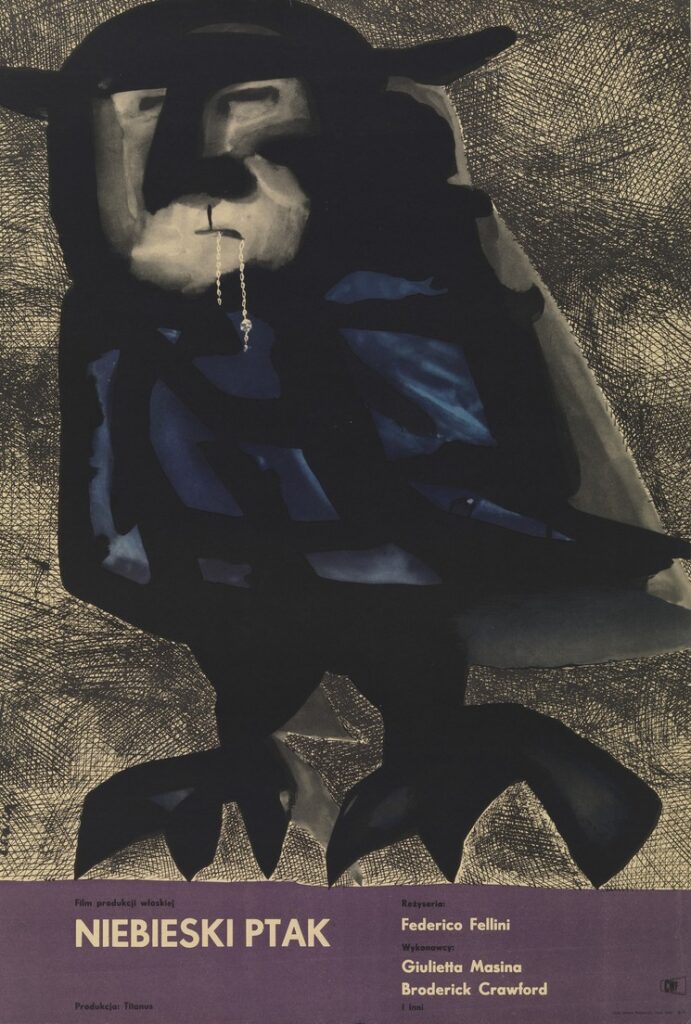

The Polish School of Posters stands as one of the most distinctive movements in the history of graphic design. Emerging in the aftermath of World War II, it transformed a medium into space for artistic expression, metaphor and intellectual play. At a time when much of Europe was rebuilding, materially and culturally, Polish poster artists developed a visual language that was bold, symbolic, and deeply personal.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

Historical Background

The origins of the Polish School of Posters are inseparable from Poland’s political and cultural situation after 1945. Following the devastation of World War II, Poland fell under socialist rule and became part of the Eastern Bloc. The state controlled most forms of cultural production, including publishing, cinema and advertising. Posters became one of the primary tools for promoting events, largely because commercial advertising as it existed in the West was limited or nonexistent.

Paradoxically, this system created unusual creative freedom for poster designers. Since posters were not directly tied to market competition, artists were not required to follow strict branding rules or realistic representation. Censorship existed, but it focused mainly on overt political messages. Cultural posters for films or theater plays were often treated as secondary, allowing artists space to experiment with abstraction, metaphor, and personal interpretation.

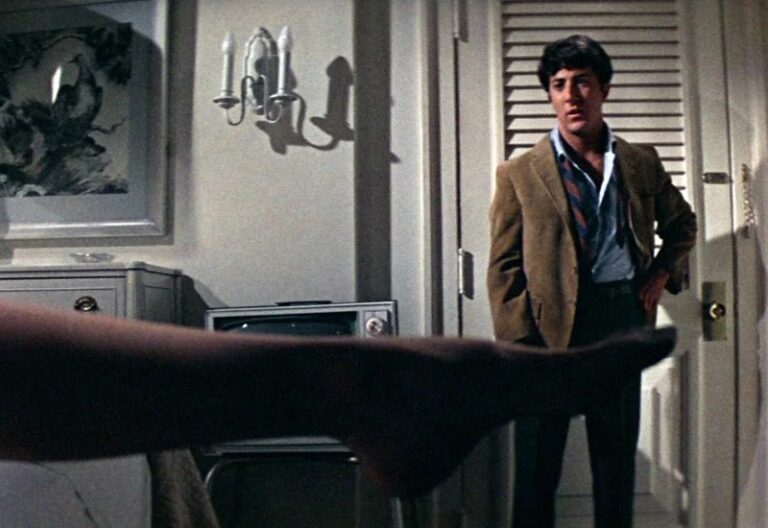

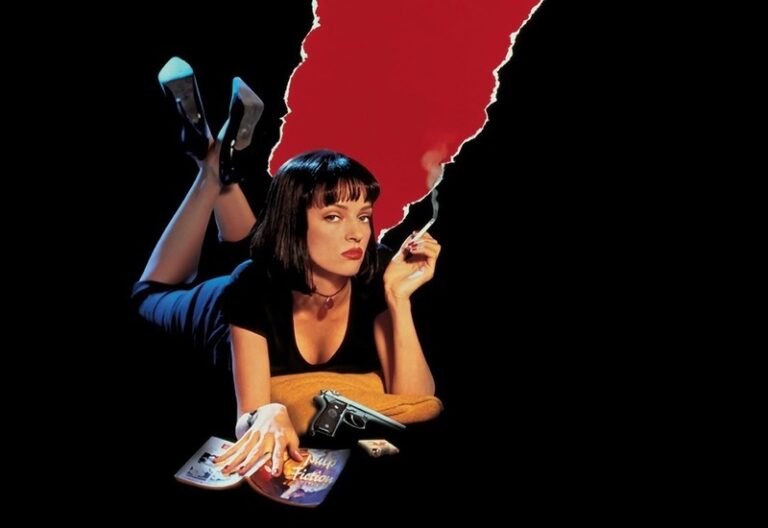

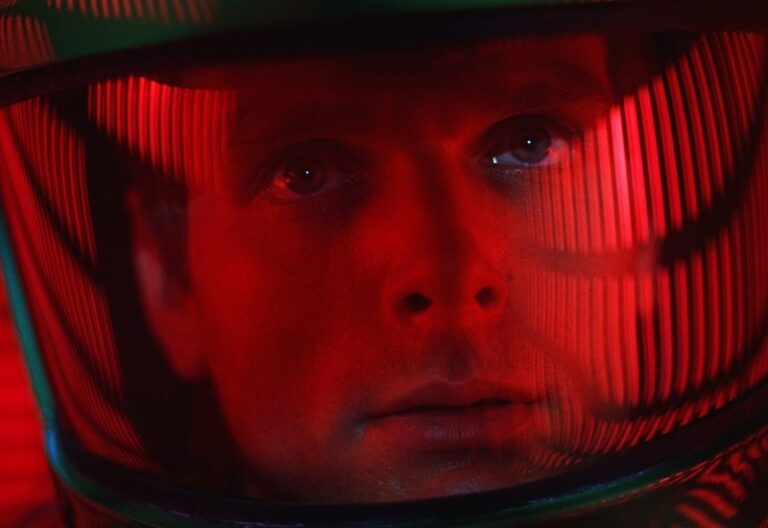

This environment gave rise to a generation of designers who approached poster-making as a form of authorship rather than mere illustration. Instead of reproducing actors’ faces or narrative scenes, Polish artists created conceptual images that captured the emotional or philosophical core of a film (or play).

How the Movement

Took Shape

The Polish School did not begin as an organized group or manifesto. It developed organically during the late 1940s and 1950s, centered largely in Warsaw and supported by institutions such as the Academy of Fine Arts. Many poster designers were trained painters, illustrators, or graphic artists, and they brought those sensibilities directly into their poster work.

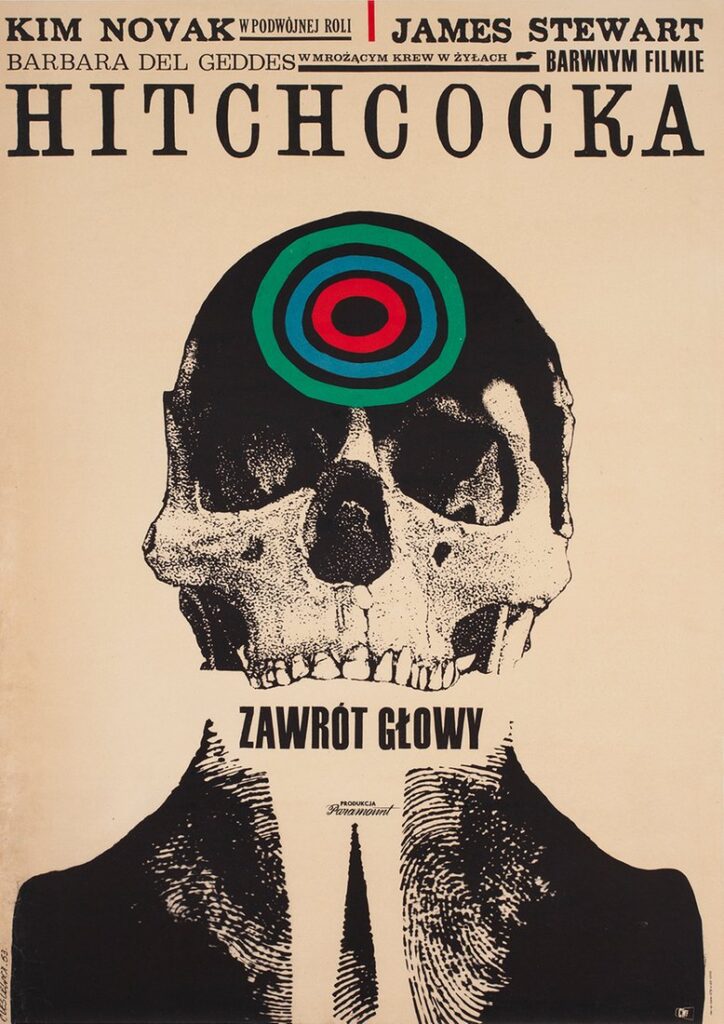

A crucial turning point came in 1948 with the founding of the state-run film distribution company Film Polski, which commissioned artists to design posters for both domestic and foreign films. This created steady demand for posters and allowed artists to build recognizable visual identities. Over time, a shared approach emerged: expressive drawing, painterly textures, hand-lettered typography, and strong reliance on metaphor rather than literal depiction.

International recognition followed in the late 1950s and 1960s, particularly after Polish posters were exhibited and awarded at events such as the International Poster Biennale in Warsaw, first held in 1966. By then, the term “Polish School of Posters” was already being used to describe a coherent visual phenomenon.

An important institutional milestone came in 1968 with the opening of the Poster Museum in Wilanów, near Warsaw. It was the first museum in the world dedicated entirely to poster art, signaling official recognition of the medium’s cultural value.

Defining Characteristics

What distinguishes the Polish School of Posters is its emphasis on interpretation rather than information. The poster was treated as a visual essay, offering a subjective reading of the source material rather than a literal summary. Humor, irony, and ambiguity played central roles, often encouraging reflection instead of immediate recognition.

Visually, these posters favored bold compositions, expressive brushwork, and unexpected juxtapositions. Human figures were frequently distorted, fragmented, or rendered symbolically, suggesting vulnerability, anxiety, or alienation. Color was used emotionally rather than descriptively, with muted tones, stark contrasts, and somber palettes appearing alongside moments of sharp visual intensity. Typography was integrated into the image itself, hand-drawn and uneven.

The influence of surrealism and expressionism was especially strong. Dreamlike imagery and visual metaphors allowed artists to hint at psychological and social tensions without explicit commentary. In a society shaped by censorship and ideological control, this indirect language became a powerful tool.

Posters often conveyed a sense of melancholy, unease, or quiet resistance, reflecting the emotional atmosphere of life behind the Iron Curtain. Rather than depicting political slogans, they expressed inner states shaped by restriction, uncertainty, and contradiction.

Significance and Cultural

Impact

The significance of the Polish School of Posters lies in how it redefined the role of graphic design under conditions of political limitation. While commercial design in the West often aimed for clarity and persuasion, Polish poster artists used ambiguity and metaphor to carve out a space for personal expression.

Within Poland, these posters became part of everyday visual culture. Displayed in streets, cinemas, and public spaces, they offered subtle commentary on contemporary life. Their dark humor, introspective tone, and occasional sense of despair resonated with audiences who recognized the unspoken realities they alluded to. In this way, posters functioned as a quiet form of cultural reflection rather than overt protest.

Internationally, the movement challenged Western assumptions about art produced behind the Iron Curtain. Instead of rigid socialist realism, Polish posters revealed an inventive and psychologically complex visual language. They showed how constraint could lead to innovation, and how artists could respond to political pressure with symbolism rather than direct confrontation.

The movement also elevated the status of the poster artist. Designers were recognized as authors, often signing their work and developing identifiable personal styles. This emphasis on individuality, achieved within a collective system, influenced later generations of graphic designers who sought to assert a personal voice within applied arts.

Famous Poster Artists

Several artists became central figures of the Polish School of Posters. Henryk Tomaszewski is often regarded as its founding figure. His work emphasized simplicity, wit, and metaphor, using minimal forms to convey complex ideas. Tomaszewski also taught at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, directly shaping the next generation of designers.

Jan Lenica brought a darker, more surreal tone to his posters incorporating fragmented figures and unsettling imagery. His work bridged graphic design and experimental animation, further expanding the movement’s artistic range.

Waldemar Świerzy combined painterly technique with strong color contrasts and expressive faces, particularly in his jazz and music posters. His portraits were dynamic and emotionally charged, capturing movement and rhythm.

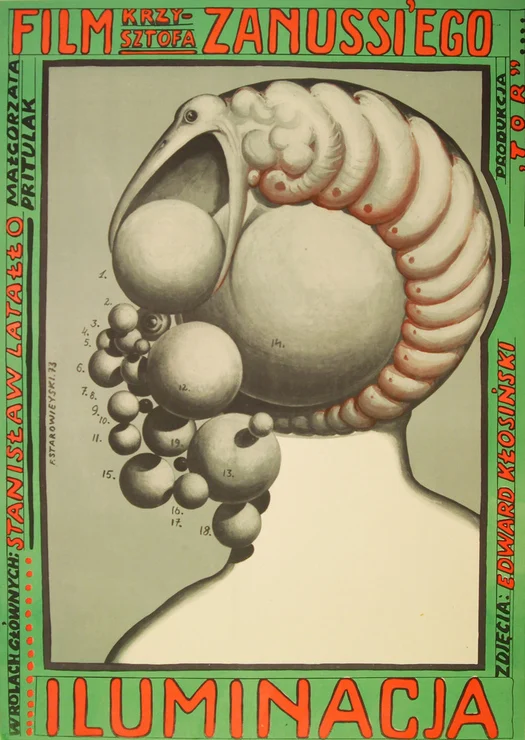

Other important figures include Roman Cieślewicz, whose work later influenced French graphic design, and Franciszek Starowieyski, known for his baroque, grotesque imagery and fascination with anatomy and decay. Together, these artists demonstrated the diversity within the movement, united by attitude rather than uniform style.

Global Influence

and Legacy

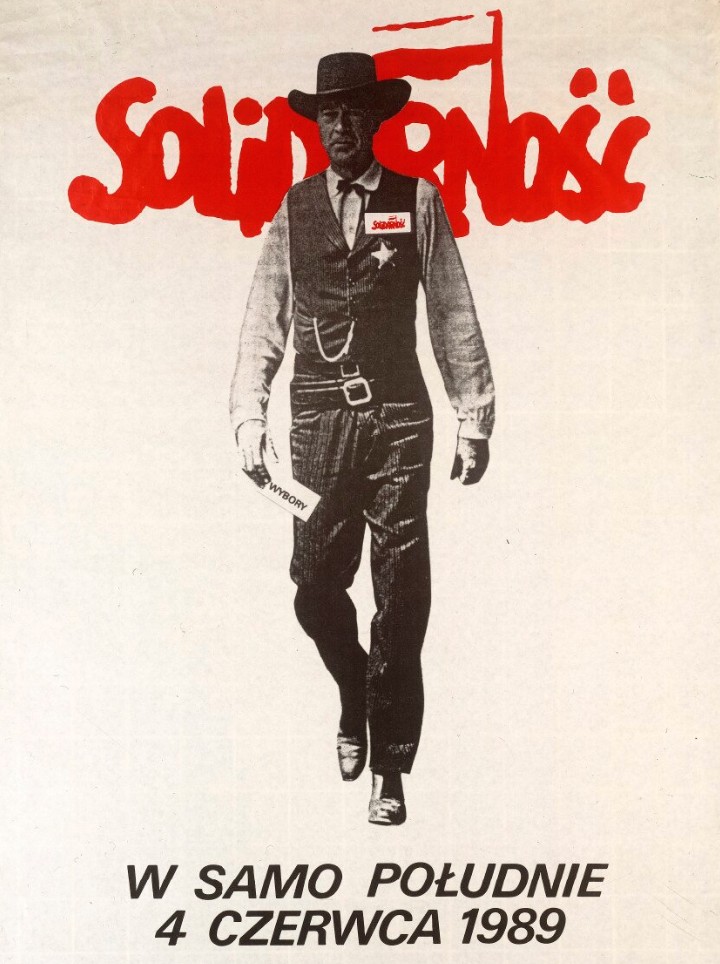

The global influence of the Polish School of Posters extends beyond graphic design into political visual culture. While many posters were created for film, theater, and exhibitions, the same visual language later proved effective in moments of social and political transformation. By the late 1970s and 1980s, poster design became closely connected to opposition movements, most notably the Solidarity trade union.

One of the most iconic examples is the Solidarity election poster from 1989, which references the American western High Noon (1952). The familiar image of a lone sheriff walking toward confrontation was reworked to depict a figure bearing the Solidarity logo, accompanied by the date of Poland’s semi-free elections. The poster translated a global cinematic symbol into a local political statement, suggesting moral clarity, personal responsibility, and the inevitability of a decisive moment. Its power lay in indirect reference rather than explicit propaganda, a strategy long practiced by Polish poster artists.

This ability to communicate resistance through metaphor reflects the deeper legacy of the Polish School of Posters. Artists had spent decades learning how to navigate censorship, using irony, allusion, and visual symbolism to express ideas that could not be stated openly. When political conditions shifted, those same tools became instruments of collective expression. Posters no longer hinted quietly at unease but openly aligned with social change.

Internationally, Polish posters reshaped how designers approached authorship and meaning. Their influence can be seen in contemporary political graphics, protest art, and cultural posters that favor symbolism over slogans. Museums, archives, and design schools worldwide continue to study and exhibit these works, recognizing them as examples of how visual culture can respond to political pressure without sacrificing artistic integrity.

The legacy of the Polish School of Posters lies not only in its aesthetic innovations but in its ethical stance. It demonstrated that even under restrictive systems, design could remain thoughtful, critical, and human. Through metaphor, darkness, and restraint, Polish poster artists created images that spoke quietly yet carried lasting force, influencing generations far beyond the borders of Poland.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

Also referred to as the Polish New Wave, is an influential film movement that originated in the post-World War II era. It stands as a beacon of creativity and intellectual exploration…

The Cinema of Moral Anxiety, or Kino Moralnego Niepokoju in Polish, represents a pivotal movement in Polish cinema, developing during the 1970s and continuing into the early…

Juxtaposition is a powerful storytelling technique where two or more contrasting elements are placed side by side to highlight their differences or to create a new, often more…

Since the birth of cinema in the late 19th century, film has held an enormous cultural power. But with that power has come scrutiny — and often, suppression. The history of censorship…

Postmodernist film emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, rooted in the broader cultural and philosophical movement of postmodernism. It started as a reaction to the…

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…