what is baroque cinema?

Cinema has always been fascinated with grandeur. From the earliest days of film, directors searched for ways to overwhelm, dazzle, and impress. Among the styles that shaped this pursuit, baroque cinema stands out for its richness and theatrical power. To understand its place in film, we first need to look back to the baroque period itself, a time when art was defined by dramatic tension, ornate beauty, and constant contrasts.

Published by: CinemaWaves Team | Filed Under: Film Blog

The Baroque Period in Art and Culture

The baroque period emerged in Europe during the 17th century and extended into the early 18th century. It was an age of grandeur, closely tied to the power of the Catholic Church and the rise of absolute monarchies. Where Renaissance art had focused on harmony and balance, baroque art aimed to overwhelm.

It used dramatic lighting, theatrical compositions, and a heightened emotional charge to draw the viewer. Painters like Caravaggio filled their canvases with stark contrasts of light and shadow, while architects such as Bernini designed churches and palaces that seemed to defy gravity with their flowing curves and elaborate decoration. Music too carried this spirit, with composers like Bach and Vivaldi creating works that emphasized complexity and movement.

At its core, the baroque was about sensation and persuasion. It was meant to stir the emotions, to immerse the audience in a kind of visual or auditory drama that left no space for detachment. These qualities are precisely what cinema would later rediscover and reinterpret.

Baroque in Cinema: Origins and Development

When film critics and theorists speak of baroque cinema, they usually refer to a set of stylistic qualities that echo that earlier artistic tradition. Baroque cinema emerged as filmmakers began to exploit the medium’s ability to create dazzling visual effects, dynamic camera movements, and layered compositions that filled the screen with detail.

From the 1940s and 50s, certain directors embraced a heightened visual language that could be described as baroque. Orson Welles, with his deep-focus cinematography and exaggerated camera angles, created a sense of spatial abundance that critics linked to baroque aesthetics.

Federico Fellini also embodied this spirit, filling his films with pageantry, grotesque detail, and dreamlike excess. Later, directors like Ken Russell, Sergei Parajanov, and Peter Greenaway developed styles that reveled in spectacle, ornament, and sensory overload.

Baroque cinema is not confined to a particular country or era, but appears wherever filmmakers push beyond realism and toward a heightened vision that foregrounds artifice, theatricality, and visual density.

Characteristics of Baroque Cinema

Several traits define the baroque approach. First is movement. The baroque thrives on dynamism, whether in the form of long tracking shots, swirling camera movements, or rapid montage.

Second is excess. The mise-en-scène is often filled with costumes, decorations, colors, and symbolic objects, creating a sense that the screen is spilling over with detail.

Third is theatricality. Baroque cinema often blurs the line between film and performance, embracing stylized acting, artificial sets, or scenes that resemble stage tableaux.

Another important feature is contrast. Just as Caravaggio used chiaroscuro to intensify emotion, filmmakers employ sharp lighting effects, extreme juxtapositions of sound, or dramatic shifts in tone.

Difference between Baroque & Neo-Baroque Cinema

Baroque and neo-baroque cinema shares a fascination with spectacle, but they emerge from different cultural and technological contexts.

Baroque cinema is rooted in traditions of European art and often linked to themes of religion, myth, or historical drama. Its power lies in theatricality, ornate imagery, and dramatic contrasts of light, movement, and emotion. Directors like Fellini, Welles, and Parajanov explored these qualities to create films that were deliberately overwhelming, echoing the grandeur of 17th-century art.

Neo-Baroque cinema, which develops from the late 20th century onward, adapts this style for a new era. It uses digital effects, globalized narratives, and postmodern Where classical baroque cinema relied on sets, costumes, and performance, neo-baroque cinema adds new layers through editing speed, CGI, and immersive world-building. The spirit remains, but the tools have evolved.

Famous Examples of Baroque Cinema

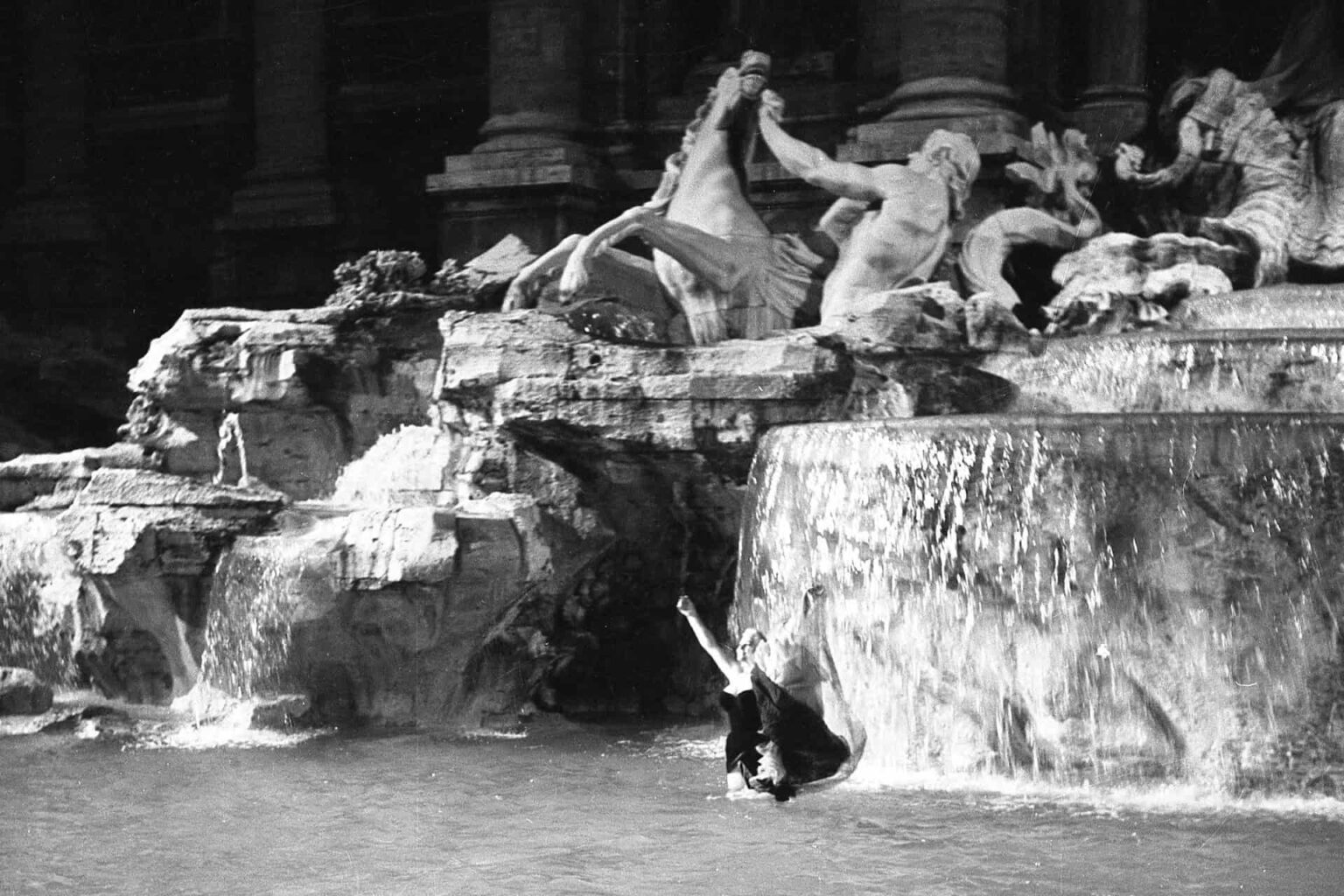

“La Dolce Vita” (1960, Federico Fellini) – Fellini’s La Dolce Vita presents Rome as both dazzling and grotesque, a city overflowing with decadence, celebrity culture, and moral disorientation. The film’s episodic structure resembles a series of elaborate tableaux, while the iconic Trevi Fountain scene captures the baroque blending of sensuality and spectacle.

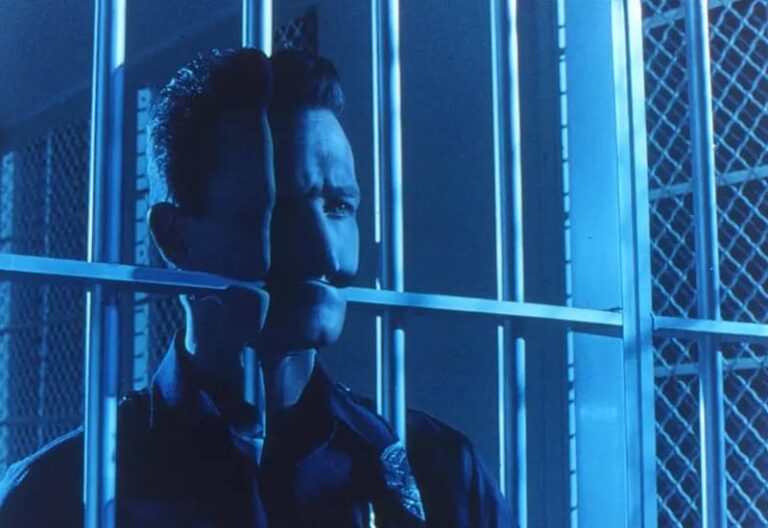

“The Trial” (1962, Orson Welles) – Reimagining Kafka’s novel as a vast baroque nightmare. The film’s towering sets, long corridors, and distorted perspectives create an oppressive atmosphere of bureaucracy and paranoia. Shot in high-contrast black and white, it recalls the chiaroscuro of classical baroque painting.

“The Color of Pomegranates” (1969, Sergei Parajanov) – Parajanov’s film abandons linear storytelling in favor of symbolic imagery drawn from Armenian art and folklore. Each frame is composed like a religious icon, filled with color and ornamentation. The result is a cinematic tapestry that mirrors the baroque fascination with allegory and spirituality, pushing the boundaries of what cinema can achieve visually.

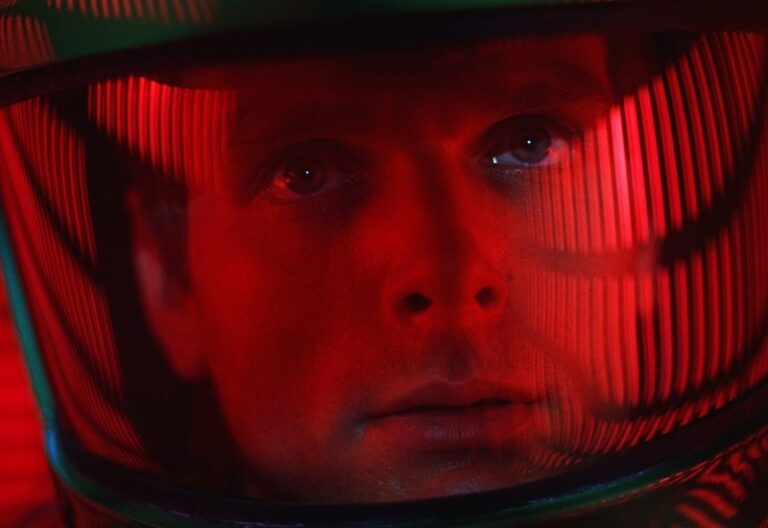

“Barry Lyndon” (1975, Stanley Kubrick) – Perhaps the purest cinematic translation of baroque painting into film. Shot with natural light and candlelight, it recreates the textures of 18th-century portraiture. Every frame resembles a canvas painted by Watteau or Gainsborough. The film’s grandeur lies in its precision and restraint, yet it overwhelms through its visual richness.

“The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover” (1989, Peter Greenaway) – Greenaway’s film is a modern baroque masterpiece, staging a story of violence and betrayal against a backdrop of lavishly designed sets. Costumes by Jean-Paul Gaultier and Michael Nyman’s haunting score intensify the sense of theatrical spectacle, turning the narrative into an operatic display of beauty and brutality.

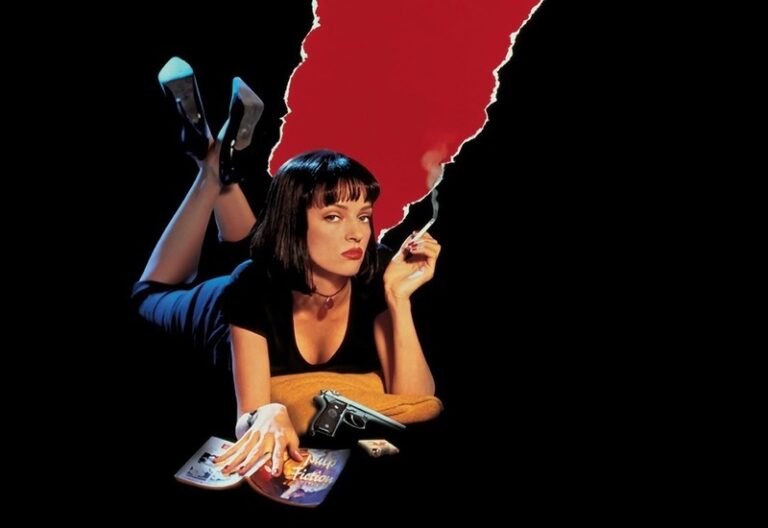

“Moulin Rouge!” (2001, Baz Luhrmann) – The film brings the baroque spirit into the age of digital filmmaking. Frenetic editing, ornate set design, and musical excess create a spectacle that overwhelms the senses. By combining pop culture references with romantic melodrama, the film embodies neo-baroque cinematic style.

Conclusion

Baroque cinema continues to fascinate because it refuses moderation. It draws from a tradition where art was meant to astonish, where movement, color, and spectacle carried as much weight as narrative. In film, this legacy translates into works that are not merely watched but experienced, pulling the viewer into carefully constructed worlds.

Even in contemporary film, the baroque spirit has not disappeared. It reappears in new forms, shaped by technology and global culture, yet still guided by the same impulse: to overwhelm, to captivate, and to hold the gaze. That persistence suggests the baroque is not simply a historical style but a recurring cinematic instinct.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

Cinematography is the art and craft of capturing visual images for film or digital media. It involves the use of cameras, lighting, composition, and movement to tell…

Mise en scène is a French term that means “placing on stage” and encompasses all the visual elements within a frame that contribute to the overall look and feel of a film. Originating…

Special effects in film have always been a kind of magic – tricking our eyes into seeing the impossible, making the unreal seem real. It’s a craft that’s been around almost…

Film theory is the academic discipline that explores the nature, essence, and impact of cinema, questioning their narrative structures, cultural contexts, and psychological…

Film criticism is an essential part of cinema, serving as a bridge between filmmakers and audiences. It focuses on analyzing, evaluating, and interpreting films, while providing…

Postmodernist film emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, rooted in the broader cultural and philosophical movement of postmodernism. It started as a reaction to the…