the rise of j-horror in the digital age

In the 90s, fear was defined by excessive gore, dark settings, and monsters in masks that chased their often-adolescent victims around their white-picket lawns. American cinema was experiencing a golden era in horror films, and the appeal for studios was evident; horror movies were cheap to make, and the output was quick in comparison to other genre films, which required a lot more effort from the post-production teams, and cult audiences gathered to assure quick profits in exchange for little time or financial constraints.

Written by: Inés Cases-Falque | Filed Under: Film Blog

But as the millennium approached, horror fatigue began to set in. American audiences turned their attention to fantasy and superhero movies, enthralled by the big-budget blockbusters. Horror was suddenly considered lacklustre, as once original content was recycled to make sequels and remakes that no longer held the same revere as their predecessors.

In fact, horror as a genre was not only considered boring, but also unnecessary. The global economic boom of the early 2000s shifted audience preference in the media they consumed; horror was a bygone genre that brought little escapism to the average viewer, whereas fantasy and sci-fi were films considered impressive and reflective of the global desire for innovation.

On the other side of the world, however, horror films emerging from the Japanese film industry were only just peaking in popularity. Instead of employing buckets of fake blood, jump scares, and post-produced screams, Japanese filmmakers were taking a more restrained approach to the genre. Suspense was favoured over surprise, building atmosphere with tension and stories that slowly unfolded to reveal the horrific truth. The objective was to get under the audience’s skin and stay there long after the film’s runtime was up.

THE CULTURAL SHIFT

TOWARDS J-HORROR

The term J-horror was popularised by Western audiences in the late-nineties when collections of Japanese horror movies were imported to European audiences by British distributors. A cult following amongst Western fans grew, and suddenly Japanese horror films were at the forefront of the genre.

The significance of Japanese horror movies, however, was already well-established in east Asia. Kaiju, a term used to categorise media involving monsters, has been immensely popular with Asian audiences since the release of Godzilla (1954) highlighted the trauma experienced by the Japanese people after the nuclear bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

Other horror classics like Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968) all relied on ancient Japanese folklore as source materials that were already well-known by Asian audiences. House (1977) was made as a response to the success of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), though Japanese filmmakers realised that they had little interest in replicating the blockbuster style of the American studios and instead opted to make films that were far more surrealist, experimental and weird.

In 1991, director Norio Tsurata released his film series Scary True Stories (1991–1992), which, while modest in scale, was influential in shaping the atmospheric style that would later define J-horror. These anthology films leaned into urban legends, subdued tension, and the suggestion of the supernatural rather than overt gore, elements that became hallmarks of the genre.

LANDMARK FILMS OF THE LATE 90s

It wasn’t until the late 90s, when Hollywood horror was coming to a standstill, that American audiences truly took notice. Ringu (1998) provided the cultural shift that had been in the making for years. Set in modern-day, urban Japan, Ringu follows a reporter investigating a cursed videotape of a ghoul in the form of a young girl who emerges from a well to seek revenge on the people who watch the tape.

The film is deeply rooted in folklore and the Onryō, a vengeful spirit who seeks revenge after being betrayed, often in the form of a female entity to represent social injustice. Ringu was immensely popular around the world and even spurred an American remake that was fairly well-received by audiences and critics. The collide of the East and West in terms of film had arrived, and the two demographics suddenly had a lot more in common than not in terms of the media they viewed.

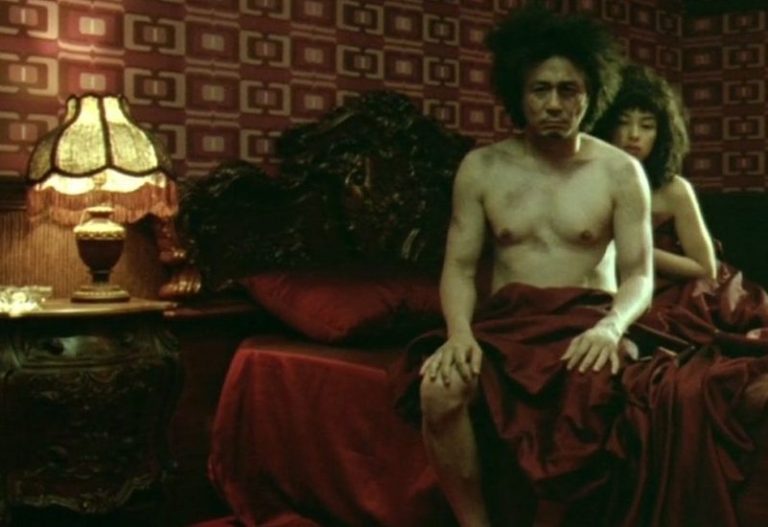

Following this international breakthrough, films capitalising on the growing disparity between women and men, and the dispelling of gender roles, rose in popularity too. Takashi Miike’s Audition (1999), though now considered a cult classic in the J-horror scope, was met with shock due to its subject matter. The film takes place in modern-day Tokyo and capitalises on the loneliness many were subjected to in the blossoming digital age; people prioritised technological advancement and career ambitions over human connection, and so the success of Audition could be due to its timely release in the socio-cultural zeitgeist.

The plot follows a middle-aged widower who seeks out a new relationship by conducting a series of auditions with eligible, young women. He becomes enamoured with a particular applicant called Asami, who hides a dark past and vengeful spirit under her external innocent appearance. Asami’s character can be compared to the folkloric vengeful spirits that are commonly found in old Japanese stories. Due to the abuse she endures at the hands of her stepfather, she seeks revenge on men who lust over her.

THE FEAR OF THE DIGITAL AGE

It’s worth mentioning that a reason why the East and West were finding common ground in j-horror media may have been an indicator of a wider fear of the new digital age emerging at the time. Modern life was suddenly emboldened by technology, which was continuously developing at a rapid rate, and people were grappling with a new way of life that threatened to leave them behind if they didn’t keep up.

The rise of the internet also provoked fear amongst adults who were now raising their children with access to a budding digital world. It’s no coincidence that j-horror films like Dark Water (2002) featured children in central roles; it reflected the parental fear of raising their children in a world they no longer recognised. Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001) effectively captures this sentiment too, as it follows young adults and university students being haunted by techno-spirits on a computer disk. Kurosawa became, and still is regarded as, one of the great J-horror filmmakers.

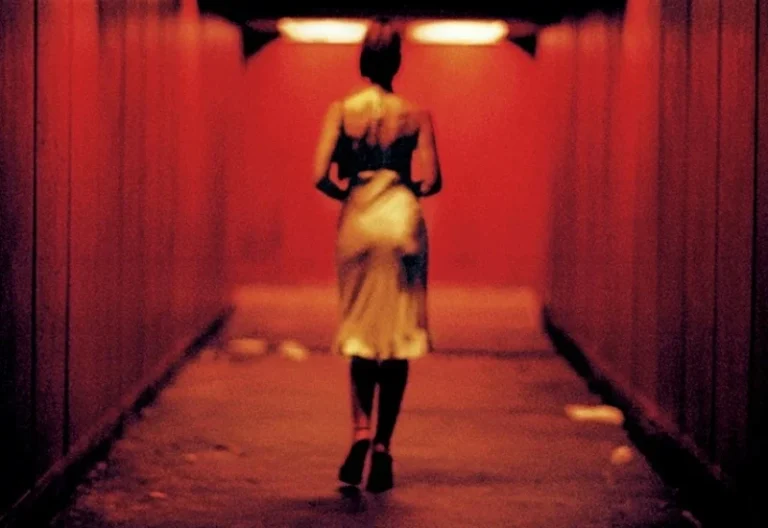

But it’s Cure (1997) that remains a highlight in his filmography, as he wove together tension and suspension to find the fear buried deep in his audience’s psyche. The film follows a detective who investigates a string of murders all connected by the X symbol engraved into the victims’ necks. The murderers are found next to their victim, but they have no recollection of their own murderous actions and seem to have been hypnotised by a third-party. This J-horror classic is a masterpiece in manipulating horror with atmosphere.

It’s a slow-burning story; there are no major scares or shocking moments, but the horror creeps up on its viewers, and the brutalisation comes from the lack of shock value. This is a kind of horror that lives among us, that permeates our daily lives. Kurosawa, as a filmmaker, understands that the scariest idea that can be translated onscreen is the truth. Horror in our daily lives does not provide us with jump scares and cheap thrills, but the reality is that horror can be found in all of us, in places we frequent and people we know. The scariest aspect of horror is the inescapability of it.

THE FUTURE OF J-HORROR

This year, Kiyoshi Kurosawa returned to the horror scene with his latest film Cloud (2024) after a string of drama efforts receiving critical acclaim. Cloud also received acclaim, although its popularity amongst international audiences faltered. The golden era of j-horror and its appeal to a global demographic hasn’t diminished, but the current streaming era has captured the attention and released their own films and series at a rapid rate.

As the digital modernity becomes less of a niche and more of a commonality around the world, its appeal as a ‘horror’ trope has always subdued. In fact, gothic horror seems to have made a swift comeback, as horror audiences have become saturated with the presence of social media and technology. Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu (2024) and Ryan Coogler’s Sinners (2025), both period horrors, have coaxed in a new golden era for American horror movies.

The return of zombies in Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later (2025) has also ushered in a new monster fascination in the western world, perhaps a post-pandemic fascination following the COVID-19 quarantines. But American and British films haven’t always sparked much excitement in the east; none of the thrice mentioned films did particularly well outside of Western markets, with many horror films never even being released overseas. Unlike a couple of decades ago, the divide in the media enjoyed by either side of the world seems to have regrown.

The hysteria for j-horror may have quelled since the late-nineties and early-2000s, but that doesn’t come without the potential for a new age of Japanese horror films. As time allows for creative ideas to evolve, filmmakers continue to discover these past horror gems, and the fear they sparked will continue to inspire in the future.

Refer to the main page for more educational insights on filmmaking and cinema history.

The Korean New Wave is a transformative period in South Korean cinema that not only captivated audiences at home but also gained international acclaim. Marked by…

The Tokyo of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s “Pulse” is the city at its most melancholy. Everything is enveloped in a grey fog. The sun is afraid to show its face. Brutalist architecture looms over everyone…

Giallo is a subgenre of horror-thriller films that started in Italy, characterized by its unique blend of murder mysteries, psychological horror, eroticism, and stylized violence….

Wuxia, meaning chivalrous hero, refers to a genre of Chinese fiction and film that follows martial artists upholding justice in ancient China. Though deeply rooted in classical…

B movies have long been a staple of the film industry, existing in the shadows of their higher-budget counterparts yet cultivating their own unique legacy. These films…

Cinema as an art form, has the unique ability to challenge societal norms, push the boundaries of storytelling and provoke intense emotions. One of the most striking…