choose me review

film by Alan Rudolph (1984)

The songs of Tom Waits are not meant to be played during the day. If you try to do so, your radio pops, the speakers fry, gravelly thirdhand accounts of weary waitresses and soulful stevedores lose all meaning; the syllables garble and become indistinguishable from lawn mower whine, TV infomercial. It cannot be done, The Lurid Romanticism of Casually Employed Souls cannot coexist with such mundanity.

Review by: James Carneiro | Filed Under: Film Reviews

August 07, 2025

Call me a temporal fetishist—this dovetails neatly with my longtime opposition to morning sex—but the night is magic, as irrational that may feel under the sun’s Protestant glare. But as the Earth rotates and the halogen hypno-summons all manner of lonely firebug, you can crank Ol’ Tommy right the fuck up; it’s his time.

Loneliness is key. Downtown Los Angeles, which Choose Me adopts as a tragicomic stage for scenarios of Waitsian import, might be the most alienating urban setting in America. It makes Wall Street after 10 PM look positively humanist. The infrastructure is foreboding, the sprawling emptiness terrifying. Minute pools of arc light, blobs of neon advertising LIQUOR or CAROLINE SAYS or CHECKS CASHED, these are your only succor, and they’re football fields apart.

Is it worth incurring so much danger with only the parking meters for company? Ordinarily, this would necessitate traveling in packs with your burliest friends, but you aren’t out searching for friends. You’re cruising for someone to slake the marrow-deep loneliness which you manage to distract yourself with trivial bullshit during the day.

All prior attempts—whether ending in aborted marriage or leadbellied lover—might seem to suggest that true love is a Hallmark psyop, that soul mates only exist in horoscopes. But still, as the moon rises with your loneliness and Tom’s syntax—incredibly, rotgut cynical and cornball romantic at once—coaxes you into the streets, you say to yourself; let this be the last time.

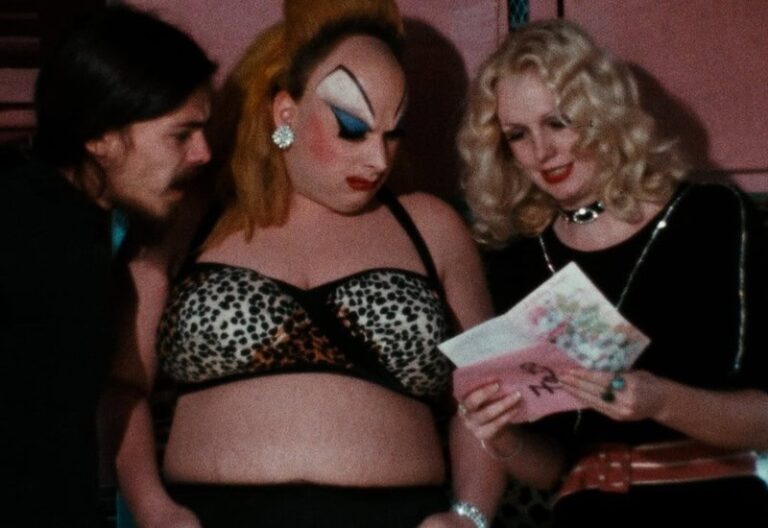

Eve and Mickey are central casting from something off Nighthawks at the Diner. Perhaps an uncharitable critic might find them “broad,” but I was immensely taken with both high maintenance machines. It takes a level of finesse to Embody A Type without becoming suffocated by it, to imbue it with a certain improv idiosyncrasy. Alan Rudolph allows them to do so with grace. His tableau—intentionally stagey, vivid with background-foreground acrobatics, sorta Altmanian use of overlapping dialogue tracks; I loved how we can hear BG-FB distinctions, even observe them swap places, blur—is immaculate. Aural-visual textures cavorting from front center to up left and back again. I took great pleasure in all of Rudolph’s Waitsian Staging, for it (mostly) distracted me from a flaccid screenplay.

Mikey (Keith Carradine, never more alluring in the suggestion of danger) is Miles Davis cool. His face, all angular dagger edge, drips with globetrotting poison. His physique, as cut as Howie Radner’s vocation, is very nearly perfect. Unlike mine, his torso is completely hairless. His hips resemble the fins on those pre-OPEC interstate trawlers. Had I encountered this character at 15, my immediate reaction would be to carve idols of him, construct a shrine in my bedroom closet among the dogeared Chuck Klosterman. I would have considered him an aspirational figure, perhaps something I could grow into once I left my parents’ house. (This never happened. Instead I grew into Alvy Singer.)

Should we clock Mikey as an aspirational figure? He is a congenital bullshit artist—yes, I know Rudolph gifts us Proof of Romantic Past as a sop to Realism Heads, but no amount of German loan words or back issues of Pravda can fully justify the level of truth-subterfuge Mikey indulges in; he simply has The Eyes of A Sexy Cult Leader—and he has an erratic, pushy nature, one which most people would categorize as “needy” if not for his coiled potency.

He’s not even a competent brawler (indeed, Rudolph deflates any and all macho combat to slapstick, which provides some of the best laughs) but still, he exudes danger, which is a panacea for loneliness if not necessarily the scaffolding for Sustainable Life Partner Fulfillment. I think the bravest thing Choose Me has to say is, “True love, soul mates, we will never have these things. We are not The Beautiful People. But you can feel a little less lonely (and get off!) in the arms of someone who was equally alienated until they met you.”

Eve (Lesley Ann Warren, dragging that thrice-married 70’s DEFA moxie stateside for the enlightenment of American women everywhere) is as cool as Mikey, if not cooler. She’s certainly more relatable. How many times do we enter ill-advised couplings, inaugurate a relationship where one party does all the work, the other coasting on entitlement or inertia?

Situations where you’re either Bowled Over By The Cool (and therefore desperate and needy) or Condescending To Your Amorous Project (and therefore callous and belittling). In their own perverse way, I think both power dynamics are shaped by loneliness, an inability to engage with the other as equals. Alienation, deference, mutual resentment, feelinglargaller; is this nominally less lonely than doing the monk thing? Perhaps. My 20’s would absolutely have been less exciting if I hadn’t spent them enmeshed in a series of situationships, scuttled for reasons both arbitrary and logical, humane and cowardly. I’ve been Eve, Mikey, Nancy, Pearl. (I’ve never been the Euro-Sleaze Bulldozer. Inshallah, we will boil him.)

Choose Me is an ensemble piece—and I always admire the attempt to inflate Central Casting—but none of these people, even when they have moments of seeping pathos, measure up to The Yearning Immensity of Mikey & Eve. They feel less there, walk-on parts in the scuttled novelization.

“Nonentity” would be hugely unfair, but Rudolph has simply neglected their development. He tries in fits and starts, Nancy’s fractured identity of One Who Coolly Dispenses With Relationship Cures While Wildly Inexperienced Herself being particularly inspired, but it feels so much less immediate, compelling. There are whirling entrance/exits of mob drama, Oswald-type intrigues, and while Rudolph can make this more or less diverting, it can never measure up to that originally proposed thesis: “Can the search for erotic/amorous fulfillment, already hugely fraught by disaster film fissures of gender and class, at the very least quench the anomie?”

It’d be easy to offer a pat “no,” as the film’s closing Graduate pastiche may suggest, but I choose to believe otherwise; we did so much work to get here, we do deserve better from a partner, from living arrangements, from workplace camaraderie, from cumming on a semi-reliable basis. And Rudolph’s downtown tableau, so rich and so perforated with noir yearning, may be disconcertingly glib, but glib is (rarely) so totalizing a force as to suggest nihilism or misanthropy; it’s the gilding on a far deeper iceberg. It’s a defense mechanism for those who, in spurts and false starts, continue to sigh-swoon.

I once heard a coworker describe Tom Waits’ discography as “thuddingly misanthropic,” but I forgave him; he must’ve been listening in the afternoon.

Author

Reviewed by James Carneiro. Initially caught the film bug while cruising for used copies of Bergman flicks/bootleg concert footage at Disc Replay. These days, he’ll review quite anything, though he is partial to Italian neorealism, American underground film, and whoever is using cinema as a method of interrogating power structures. You can follow him on Letterboxd and Twitter.

A 1993 British black comedy drama film starring David Thewlis as Johnny, a loquacious intellectual, philosopher and conspiracy theorist. The film won several awards…

Shareen and Claire, a lesbian couple living on Staten Island, find themselves ensnared in a vast conspiracy involving a ghost ship of nuclear refuse, ominous television…

Envisioned on the picturesque coast of Southern California and based on the book of the same title, the collaborative efforts to put Midnight Cowboy on screen…

American eccentric cinema is a distinctive style of filmmaking that surfaced in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, characterized by its quirky characters, whimsical…

A cult film is a movie that builds a devoted following without achieving mainstream success or widespread critical praise at the time of its release. These films are…

Neo noir is a contemporary style that draws from the classic film noir genre from the 1940s and 1950s. Classic film noir became known post-World War II, characterized…