where to begin with béla tarr

Béla Tarr is one of the most respected Hungarian directors and is also a pivotal figure in the genre that is “slow cinema” which is a style that prioritises stillness, long takes, and atmospheric storytelling over traditional plot-driven narratives. He is a figure who has gained a cult-like following, but it is clear that his films are not for everyone due to often being long and bleak.

Written by: Max Palmer | Filed Under: Film Blog

It is hard to talk about Tarr without mentioning his aesthetic and the overall feeling. A good comparison to Tarr is Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky who also uses long takes and philosophical dialogue, but this is where the comparison ends. American film critic, Jonathan Rosenbaum, has named Tarr a “despiritualised Tarkovsky”, since Tarr’s work often explores the loss of faith, while Tarkovsky’s films, most notably Andrei Rublev (1966), revolve around faith as a central theme.

Tarr’s films are commonly seen as nihilistic and overly philosophical, but this was not always the case. His earlier works, which are anything before Damnation (1988), align more closely with Hungarian social realism films, a style which focuses on the lives of normal and working class people.

This style, seen in other Hungarian films such as Valahol Európában (1948), and echoed by the Budapest School movement, would have been a lot more commercially marketable for Tarr as he was starting out. His debut Family Nest (1979) exemplifies this approach, using non-professional actors and a documentary-like style to depict domestic and social tension. This isn’t to say that his later works aren’t social realist pieces but they tend to cover a wider theme of the human condition and human suffering.

Even in these early works, seeds of Tarr’s signature style are present, including a focus on the mundane, repetitive aspects of life, and an atmosphere of desolation and alienation with the only close comparison being films such as Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975).

A question newcomers tend to ask when they are trying to get into Tarr is ‘where do I start?’, and the most common answer is his seven and a half hour magnum opus Sátántangó (1994). However I strongly disagree with this since the dense themes and long runtime may be overwhelming for a first time viewer.

So where to begin with Béla Tarr?

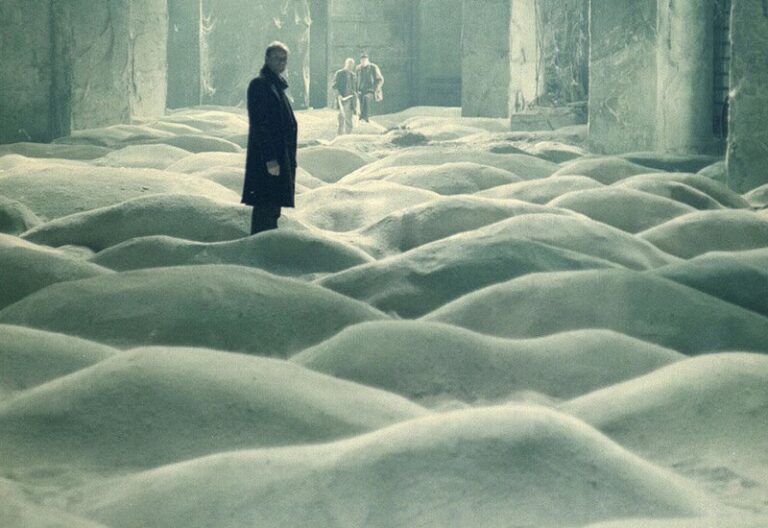

If you want a quintessentially Tarr film without the (somewhat) extended runtime I would recommend Werckmeister Harmonies (2000). This film captures everything that makes Tarr’s films so special and beautiful, from his long tracking shots all the way to the beautiful music from Mihály Vig, a longtime collaborator with Tarr.

The film follows János, a local postman, who witnesses a mysterious circus arrive in his town, catalysing rebellion and violence. It explores how people are conditioned to follow rules they no longer believe in, leading to a slow but inevitable breakdown of order and the descent into chaos.

If you enjoy Werckmeister Harmonies the next step is to tackle Sátántangó (1994) since it is debatably his best and most famous film. I believe it is best to go into a film as blind as you can but I believe with Sátántangó that is not the case. It is important to know some of the context behind the film before watching it to fully appreciate the beauty of Sátántangó.

The first (and perhaps the most controversial) thing I would recommend is not to read the book it was based on by László Krasznahorkai. The book is fantastic, don’t get me wrong, but going into the plot as blind as you can will give the most visceral and gut punching experience.

Secondly I suggest reading up on 20th century Hungarian history, particularly the communist rule in the 80s since that is when it is set. Like many filmmakers, Tarr often crafts films as a reflection of his country. Knowing what happened politically in Hungary in the 20th century will give you a better understanding of many of the plot points.

After you have slain the beast which is Sátántangó the path splits into two, if you want something different to Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies the obvious place to go to is his early works which include Family Nest (1979), The Outsider (1982) and The Prefab People (1982).

However if you want something which is similar to Sátántangó for the bleak themes and long runtime I recommend his final film The Turin Horse (2011). This is a beautiful final film for him since it has everything that makes him special but it also feels fresh and new.

Béla Tarr is a true master of his craft. While his films may feel overwhelming at first (I’ve been there), I can wholeheartedly say they are worth every moment of your time and effort.

Dive in, and let his haunting world reveal itself to you.

Author

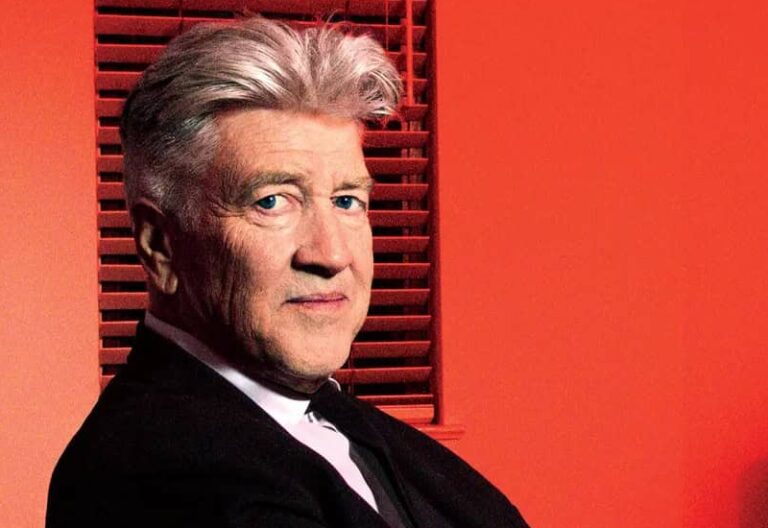

Written by Max Palmer. Based in North Wales Max has had an admiration for films ever since he got Pinnochio on DVD for his third birthday, since then he has grown to be a fan of anything and everything from David Lynch to Hayao Miyazaki. However his heart has a special place for anything shocking and underground.

The Budapest School Film Movement developed in Hungary during the later half of 20th century, a period marked by Soviet influence and political repression. Following…

The development of slow, or contemplative cinema is rooted in the history of film itself. Understanding slow cinema involves examining its evolution from early influences to its…

Experimental film, referred to as avantgarde cinema, is a genre that defies traditional storytelling and filmmaking techniques. It explores the boundaries of the medium, prioritizing…

In the late 19th century, a young Danish priest travels to a remote part of Iceland to build a church and photograph its people. But the deeper he goes into the unforgiving…

Arthouse film refers to a category of cinema known for its artistic and experimental nature, usually produced outside the major film studio system. These films prioritize artistic…

Auteur theory is a critical framework in film studies that views the director as the primary creative force behind a film, often likened to an “author” of a book. This theory suggests…